In the United States, approximately 10 million pounds of 1,4-dioxane are produced each year. It is being detected in groundwater at dozens of sites across the country. Once thought to be relatively benign, new science says otherwise. Costs to clean it up are high, and communities are grappling with how to deal with it. In this installment of “The Green Room,” WEMU explores the experiences of two cities: Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Tucson, Arizona.

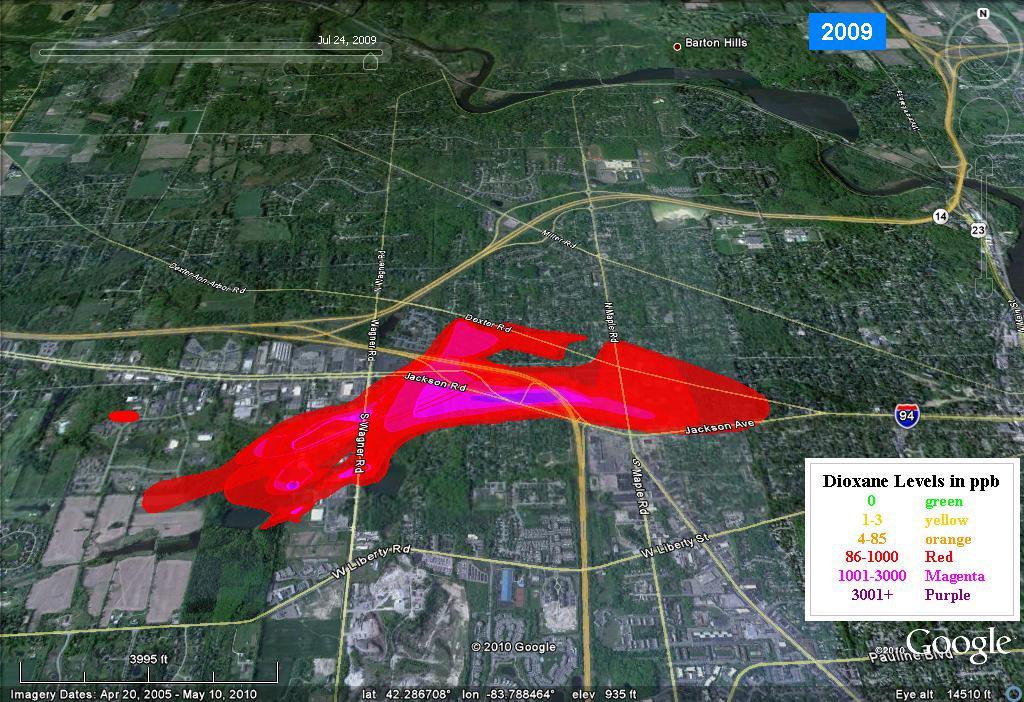

1, 4-dioxane plume, 2009. Image: Roger Rayle / SCIO Residents For Safe Water

(David Fair)– On March 14th the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality delivered news long-awaited in Ann Arbor, where the solvent 1,4-dioxane has contaminated it’s groundwater: The DEQ will soon lower the level of dioxane that is legally permissible in the state’s drinking water from 85 to 7.2 parts per billion. It’s good news, but actually restoring Ann Arbor’s aquifer to safe levels is still not part of the state’s plan. Meanwhile, the technology and resources to clean it up doexist. In this installment of WEMU’s “The Green Room,” Barbara Lucas explores the question: Will the legally responsible party get rid of the pollution, or let the plume spread?

Barbara Lucas (BL): Gelman Life Sciences on Wagner Road stopped using dioxane 30 years ago. But despite efforts to contain it, the 850,000 pounds they dumped have been spreading throughout the groundwater. Now the plume covers about three square miles, on Ann Arbor’s west side. It’s in some lakes and streams around here, too.

Evan Pratt: The Sister Lakes are just off to the northeast of us over there. We can see one of them.

BL: That’s Evan Pratt, Washtenaw County Water Resources Commissioner.

Pratt: And it sure is a nice quiet serene setting but maybe that’s appropriate for a colorless, odorless contaminant that you really can’t tell is there. No one would know this is kind of ground zero.

BL: He tells me Ann Arbor city water is safe, since it comes from Barton Pond. But because dioxane can’t be removed by boiling, or filtering at the tap, well water is at risk. And fears are it could reach Barton Pond some day.

Pratt: We could maybe go to the Pall Corporation and take a look at all the fancy gizmos they have that suck the water out of the ground and treat it.

BL: He says Pall is the company that bought out Gelman. And last year, a Canadian company called Danaher bought out Pall. Pratt is frustrated. He says ten years ago, when Pall found it challenging to remove the dioxane to safe levels, the county circuit court judge let Pall drop the cleanup goal. They created a prohibition zone instead: an area where wells are prohibited, and homes must be hooked up to city water.

Pratt: The prohibition zone limit is violated, “Well, let’s just expand the prohibition zone!” Water gets into, highly toxic water gets into a lot of wells, three or four hundred wells, “Well, let’s just put them on City water!” I don’t understand what does that means for us long term.

BL: Bob Wagner of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality says creating prohibition zones instead of cleaning up groundwater is not unusual in Michigan.

Bob Wagner: And since 1995, with thousands and thousands of cleanups that we work on, there have been 4,000 such prohibition zones–restriction zones–put in place to manage contamination, to assure the public and the environment is protected from the risk. And that is what current law provides for.

BL: Here’s Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners vice-chair Yousef Rabhi.

Yousef Rabhi: I’m trying to imagine somebody dumps a bunch of oil into the river. Is the plan to just leave the oil in there and to contain it? Or do you actually want to get the oil out? And why is this any different?

BL: Wagner responds.

Wagner: It isn’t a plan, it is an outcome, as a result of litigation.

Rabhi: To me, this is the same situation. We have pollutants underneath our feet moving towards water sources? I mean, it is inconceivable to me that we would allow a court ruling like that to just stop us in our tracks.

BL: 1,4-Dioxane is being found in groundwater at dozens of sites across the country. The Environmental Protection Agency calls it a contaminant of “emerging concern.” They’ve not yet issued an MCL, or Maximum Contaminant Level. But in response to new science, in 2010 the EPA issued a health advisory, calling 1,4-dioxane a probable carcinogen. At that time, t he EPA set the risk of one cancer death in a million at .35 ppb.

City of Tucson video: “…to supply a safe, reliable source of water, to Tucson customers…”

BL: How have other communities responded to the news that dioxane is more dangerous that once thought? In 2001, Tucson Arizona found dioxane in their drinking water, but in concentrations less than 5 ppb, averaging just 3.33. By simply blending with clean water, they could’ve diluted it to even lower levels. But they wanted to get below the EPA’s advisory of .35 ppb. Far below Michigan’s newly announced criteria of 7.2 ppb.

City of Tucson video: “…came together, to dedicate the new facility…”

BL: I call Chad Lapora, Tucson Water Programs Superintendent. He tells me the State of Arizona doesn’t even have a dioxane criteria law.

BL: Why do you go to that level, when you don’t need to, legally?

Chad Lapora: Because of the history, this utility and this city said we’ll never, we’ll never put ourselves in the position that we were in before.

BL: He’s referring to their prior groundwater contamination, by the carcinogen TCE, that resulted in a federal Superfund cleanup. Apparently, the experience made an impression. In less than three years after the EPA’s dioxane warning, Tucson had built a plant that removes dioxane to less than .1 ppb.

Lapora: When blending was no longer an option, the senior leadership at Tucson Water went to the mayor and council and said, ‘We need to build this plant’ and they signed off on it and we built the plant!

BL: Although the parties that created the pollution in Tucson are legally responsible, Tucson chose to use city money up front to get the plant built.

Lapora: We are in the process of getting reimbursed for that $16 to $20 million. And in the future, it will be set up where we get reimbursed for operations and maintenance as well, for that plant.

BL: He says they made a decision to stay under the EPA’s .35, one in a million risk of cancer deaths, even though it’s not a law.

Lapora: Regardless of how you deliver water to customers, you know, we still have to meet water quality standards. And for us, we treat–and that’s the biggest thing that I can tell you–we treat that health advisory for 1,4-dioxane as if it were an MCL. And that’s what we’ve done. We take it very seriously.

BL: Meanwhile, in Michigan, the response to the EPA’s 2010 health advisory has been different. Instead of cleaning up to a higher standard, Ann Arbor’s prohibition zone–where wells are prohibited–was expanded. And the rate of cleanup was slowed in both 2011 and 2012. Here’s Sumi Kalisapathy at the February 29th City Council Work Session.

Sumi Kalisapathy: What I have heard from MDEQ, I just feel hopeless. So I’m just looking for a solution outside MDEQ or the state. Is there any example you can think of, especially with dioxane, anywhere in the U.S., that has been better handled?

BL: City Environment Coordinator Matt Naud responds.

Matt Naud: You know, I think there are examples of really successful cleanups, and there are ways, if you have enough zeros at the end of the number, to… You know, Pall is in the filtration business. It’s their job to make water cleaner. They could pump it, and go back to using UV, and treat it to a lower standard. You could even ideally treat it to non-detect, and you could use it as residential drinking water. That’s not required under state law, it’s very expensive, and so it’s unlikely we’re going to see that as a solution.

BL: Neither state nor federal law is making Tucson remove their dioxane. They are proud of their plant. Last year it won Grand Prize in a national contest. Its award-winning technology is supplied by a company called TrojanUV. Searching the Trojanuv.com website, I open a slide show touting the treatment process used in Tucson.

Music from TrojanUV slideshow.

BL: Hmm… where have I seen the name TrojanUV? Oh yeah, it was on the environmental page of Danaher.com. Turns out Danaher has owned TrojanUV since 2004. Danaher. The same 60-billion dollar Canadian company that last year bought Pall Corporation. So, while Danaher’s subsidiary in Ann Arbor is letting its plume spread, its company in Tucson has proven it can remove dioxane to nearly non-detectable levels. Should Danaher be held to a greater level of accountability? Danaher has not responded to requests for comment.

Barbara Lucas, 89.1 WEMU News

- To learn more about whether Ann Arbor’s groundwater contamination can be cleaned up, listen to upcoming segments of ‘The Green Room.’

- There will be a Town Hall Meeting with MDEQ Director Keith Creagh on Monday, April 18th at at Eberwhite Elementary, organized by State Representative Jeff Irwin.

RESOURCES:

City of Ann Arbor FAQ on 1,4-Dioxane and Pall Life Sciences (Gelman)

CARD: Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane

March 14, 2016 Press Release from MDEQ regarding lowering of allowable Dioxane levels

Newspaper clipping history of the Ann Arbor Dioxane contamination

Collection of articles on Ann Arbor’s dioxane plume by Ryan Stanton of MLive

Tucson’s Dioxane:

Video on Tucson’s new facility to remove 1,4-Dioxane

Video on opening of Tucson’s Dioxane Treatment Facility

Tucson’s letter to customers about Dioxane Treatment Plant

1,4-Dioxane resources from the City of Tucson

TrojanUV-Pall-Danaher:

TrojanUV’s dioxane treatment system used in Tucson

TrojanUV Case Study: Tucson, Arizona

Danaher’s Environmental Page: “Our products help protect the global water supply”

This story originally appeared on WEMU’s The Green Room and is republished here with permission.

This scenario is precisely why “safe fracking” and other similar sentiments on the dispersal of toxic materials should be seen as the canards that they really are.

I have often marveled at the fracking apologists who love to claim that the residue of the undisclosed chemical slurries that they inject into bedrock during the fracturing process will never be a risk to the environment. They continuously claim that the very bedrock that their process is fracturing will contain the toxins that they are injecting – when the very process of fracturing the rock itself renders it permeable.

With the MDEQ’s head-in-the-sand approach on Ann Arbor’s (and presumably the thousands of other cases like it), it will only be a matter of time until each of these hazardous material spills, dumps or abandonments will reach our precious and finite drinking water supply. It’s only a matter of time.

Apparently those in power, both in industry and government, are hoping to kick the can far enough down the road so that those responsible will have already amassed their fortunes and stashed them in some offshore tax haven where they will be shielded from cleaning up the messes that they have created or permitted.