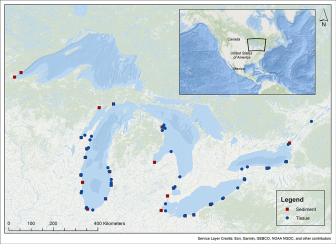

NOAA’s Mussel Watch team sampled tissue from invasive mussels and sediments at 90 sites across the Great Lakes to identify areas with high levels of harmful chemicals. Credit: NOAA

By Daniel Schoenherr

Zebra and quagga mussels have threatened Great Lakes ecosystems since they arrived in the 1980s.

Now the invasive species are acting as unlikely allies in identifying pollution hotspots.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Mussel Watch program is collecting the mollusks at sites across the Great Lakes to measure the concentration of harmful pollutants in their tissue. A report with the results, expected this fall, will serve as an indicator to communities that they may be in need of cleanup, said one of the program’s leaders.

Field researchers with NOAA’s Mussel Watch program combine the insides of zebra and quagga mussels in a container for laboratory analysis. Credit: NOAA

Mussel Watch started along the Atlantic coast in 1986 and is the “longest running continuous contaminant-monitoring program of its kind in the United States,” according to NOAA. In 1992, the effort expanded to the Great Lakes where it annually tracks pollution levels in a network of 90 nearshore sites.

The Great Lakes program measures pollution in sediment samples, but most of its data come from the invasive mussels. The tiny bivalves attach themselves to rocks and hard surfaces in and around the Great Lakes, filtering small organic particles out of the water to feed themselves.

As mussels filter water, they collect pollutants such as heavy metals and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS — toxic compounds found in consumer goods which persist so long in the environment that they’re known as “forever chemicals.”

Researchers have identified nearly 600 contaminants in the tissues of sampled mussels, according to the Mussel Watch website.

The traits that make zebra and quagga mussels problematic as invasive species also make them perfect contaminant indicators, said NOAA research biologist Ashley Elgin.

“They reproduce fast and they quickly disperse,” she said. “That helps their populations explode and helps them reach these warm, shallow areas.”

Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary educator and diver Stephanie Gandulla helped Elgin collect mussels for the program last year. Her dive team gathered samples from Lake Huron coastal sites in large bags for processing in a laboratory.

“They seem to be tough little critters, and they’re very sharp,” Gandulla said. “You use a paint scraper to get them off of those rocks and keep them intact.”

The upcoming report will analyze the distribution of PFAS across the Great Lakes based on data the Mussel Watch team collected from 2013 to 2018. The work will help identify communities disproportionately affected by harmful pollutants, said Michael Edwards, acting deputy program manager for Mussel Watch.

While the program doesn’t facilitate cleanups, Edwards said, the analysis of pollutants will help alert communities to what is in their backyard. That information may prompt action to limit the waste that industrial facilities are allowed to release into the surrounding environment.

The report is in its final stages of review expected to be released by late November, according to Edwards.