A clump of invasive zebra mussels. (Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service)

Great Lakes Echo

Invasive species are a problem, but are they a death sentence for the ecosystems that they infect?

Not quite, according to a new university study.

Invasive species, such as zebra mussels and Asian carp, are infamous for taking over the ecosystems where they are introduced. Because those species often have no natural predators in their new environment, invasive populations can grow rapidly, quickly spiraling out of control.

But a University of Wisconsin-Madison study recently published in the journal PLOS ONE found that most populations of invasive species don’t grow very large. It turns out that invasive populations that get out of control are uncommon, the research found.

“Invasive species have been seen as either they’re present or they’re absent,” said Gretchen Hansen, a fisheries research scientist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and lead author of the study. “The variations of abundance aren’t as discussed.”

Evaluating that degree of abundance will help scientists and conservationists better understand how to approach invasive species, Hansen said. By explaining that a non-native species isn’t necessarily a poison to an ecosystem, the study can help organizations plan where to best spend time and money fighting them.

“Let’s say there are 100 sites that are invaded but only 10 of them have really high abundances, well you probably couldn’t control all 100 of those sites anyway,” she said. “So if you can identify the few where the impacts could be the most devastating, then maybe you can prioritize those for control.”

The research of 24,000 populations in North America and Europe found, on average, the invaders live at three times the abundance of their native counterparts. If you found 60 invasive crayfish in a lake, that same lake might only contain 20 individual native crayfish, the study found.

While that might sound alarming, in many cases it’s not a wide enough disparity to make a monumental impact. Invasive populations still mostly occur at low enough levels that they are not easily noticed, said Jake Vander Zanden, the professor who led the study.

Common thinking is that invasive species quickly and aggressively spread through the environment where they’re introduced, said Vander Zanden. But the study proves that wrong.

“For a species to become really abundant, everything needs to be lined up right,” he said. “Everything needs to be perfect for that species, and the reality is that even for invasive species, oftentimes they’re not.”

Vander Zanden’s idea for the research began years ago while studying rusty crayfish, an invasive species to Wisconsin’s lakes. He expected to find the crayfish rapidly overtaking their new environment and was surprised to discover their population density wasn’t drastically different from the native populations in the same lake.

“For each lake there was a measure of abundance of rusty crayfish,” he said. “When I pulled up the data, I was struck by the fact that in most of the lakes, they were at low abundances or densities.

“I remember thinking that this was an unusual finding, but I didn’t really do much about it until that same situation came up a couple of years later with a different species. I started thinking to myself that this could be a general pattern,” he said.

And it is.

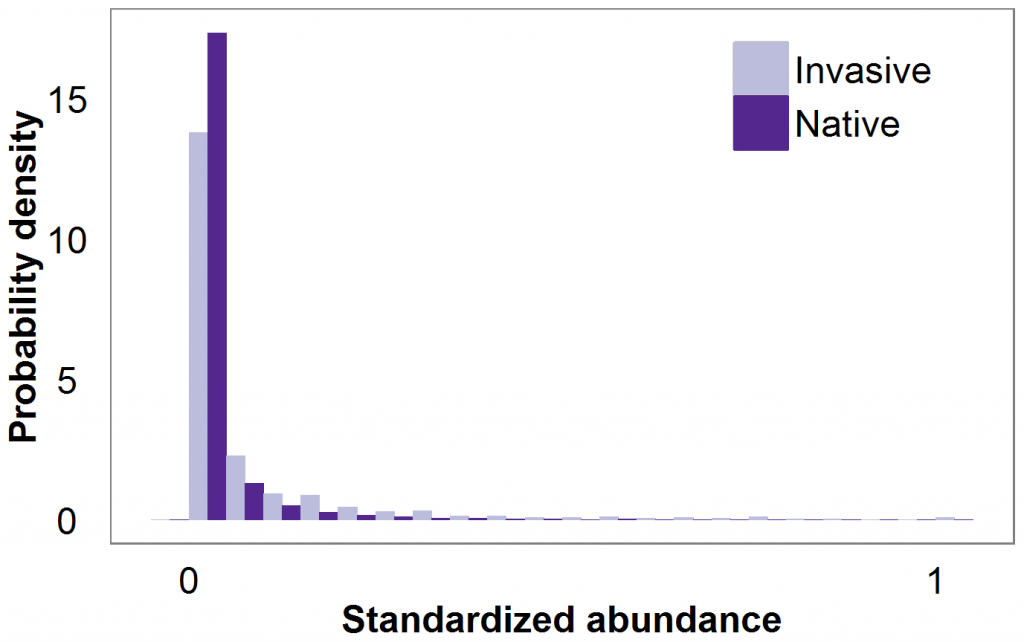

The study showed that the distribution of both native and invasive species is extremely right-skewed, meaning they generally occur at a low density within an environment.

This right-skewed graph shows the occurrence of the invasive and non-invasive species studied in the research. The majority of species live at low abundances within their environment. (Photo: PLOS ONE/University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Understanding the similar population distributions of these species will help scientists and conservationists better allocate both funds and manpower. Environmental organizations will know to focus on distributions that get out of hand, said Vander Zanden.

“It’s just another way that down the road we’ll be able to target and prioritize and get better at directing management resources like time, energy and money to where it’s most needed,” said Vander Zanden.

The next step is for researchers to figure out how and why invasive species are relatively dormant in one location and highly abundant in another. Currently, that isn’t well understood, Hansen said.

“(The study) sets the stage for some future research,” she said. “The really big question is if we can identify the places where invasive species are likely to get to high abundances, can we identify those ahead of time?”

Pingback: January 2014 Great Lakes Echo Highlight | Lagrange Hunting & Fishing Club | Just another WordPress site

IT would be good if these studies could be done in the abundant fishery of western Lake Erie. Data here shows that the invasive white perch continues to grow in numbers at the expense of the native yellow perch. Gobies are very abundant – will those numbers stay?? and quagga mussel numbers appear to have leveled off – explanations and data are welcome..