Hard to believe we’re in the thick of the holiday season now and soon will be looking forward to 2011.

Hard to believe we’re in the thick of the holiday season now and soon will be looking forward to 2011.

When I look back on all that’s happened across the Great Lakes region’s environmental landscape over the past year, I can’t help but start with simple tributes and rallying cries that crept inside my head last June as I walked along Main Street in Millbury, Ohio, with Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland, assessing damage from a tornado that killed seven people.

The disaster wreaked havoc on a close-knit community a few miles southeast of Toledo. The jaws of just about anyone who saw the wreckage dropped in disbelief. Cars, boats and pieces of houses were strewn everywhere, even up in a line of trees.

A fine community that seemed so solid and wholesome was suddenly turned upside down through no fault of its own.

As the governor and I parted, my eyes were drawn to a makeshift flagpole.

James Hayward, a 34-year-old unemployed South Toledo resident, had attached a pair of 2-by-4’s together at one end so that he could have a 12-foot strip of lumber anchored to the foundation of what had been his buddy’s house at 28765 Main.

Old Glory was flappin’ in the breeze.

“It’s a sign we ain’t takin’ shit from no one, not even Mother Nature,” Hayward explained.

Duane Lender, a 44-year-old custodian at Perrysburg Junior High School, said he and his wife, Traci, 38; their son Nathaniel, 5; two in-laws, and the family’s three daschunds had made it into the basement “with probably 10 seconds to spare.”

“It was like a freight train going over your house,” said. Lender, whose home was one of many leveled.

That setting got me thinking about a few conversations I had earlier that day with Gov. Strickland.

Unnatural consequences of natural disasters

While we were focused on the calamity at hand, I asked what kind of environmental issues might arise.

He shrugged.

I thought it was a fair question. Some of my best friends have written about environmental hazards in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

I wondered how contaminated water gets in wells after a tornado knocks a home off its foundation. I wondered where destroyed siding, lumber and building materials would go; how much mercury was in the trashed automobiles, light switches, computers and other electronics and about the freon in busted-up refrigerators.

The greatest environmental threat

But the more I looked at that flag flapping in the breeze from the foundation of Duane Lender’s former home, the more I realized there is a bigger environmental story behind every catastrophe – the loss of our sense of home.

The Rush Limbaughs and the Glenn Becks of the world mock tree-huggers and anxiety-ridden climate watchers about spotted owls and polar bears.

They would like us to believe people are somehow insulated from nature. Nothing is farther from the truth.

Anger arising over BP’s Gulf of Mexico spill didn’t stop with oil-slicked birds or dead fish.

Deep inside, Americans were offended by the assault on nearly a third of their nation’s shoreline by a multinational corporation whose executives came off in front of Congress as arrogant and indifferent.

The tragedy disrupted the sense of home for Americans who live not only in the Gulf region, but everywhere.

That same sentiment was felt in south-central Michigan last summer when a 30-inch pipeline burst near Marshall, Mich., allowing about a million gallons of oil into the Kalamazoo River, which flows to Lake Michigan.

Susan Hedman, with just four months on the job as head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Midwest regional office in Chicago when the oil spilled, told hundreds of people in a packed gymnasium that her agency would not leave until their sense of home was restored. She vowed to recover every last dime. The pipeline’s owner-operator, Enbridge Energy Partners, of Calgary, Alberta, took the rare step of offering to buy homes at their appraised or listed value.

New opportunity to solve old challenges

As we head into 2011, the Great Lakes region faces more issues that threaten our sense of home.

As we head into 2011, the Great Lakes region faces more issues that threaten our sense of home.

Asian carp threaten our $7 billion fishing industry and the thrill of catching sportfish such as walleye, yellow perch, and smallmouth bass.

A federal judge recently ruled against an attempt to stop them by blocking the waterways connecting the Mississippi River and Lake Michigan. And the U.S. House of Representatives joined the Senate in passing a bill that bans Asian bighead carp from entering the country.

As odd as this sounds, Congress hopes to do what the Mississippi River’s powerful current, a multi-million electrical barrier, trappers and bucketfuls of poison have failed to do: Keep them outta here.

The Great Lakes region will continue to be a test case for energy production – some familiar, some unproven, but each striving to help people preserve their sense of home.

Henry Henderson, who heads up the Chicago office of the Natural Resources Defense Council – the nation’s largest nonprofit group of environmental lawyers — says that the need for cleaner energy production is why his group came to the Great Lakes region and Upper Midwest.

Wayne State University’s Noah Hall, the founding executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, recently suggested that Canadians assume more risk for drilling for natural gas.

Canada has drilled from the Great Lakes shoreline and, to a limited degree, offshore for decades. The only drilling on the U.S. side is from about a half-dozen Michigan-based directional drills. Hall’s point, a valid one, is that the quality of life on the U.S. side is almost as likely to be harmed from a spill as that on the Canadian side, yet Canada is reaping virtually all of the profits from drilling.

New solutions, new consequences

Birders such as the Black Swamp Bird Observatory question the wisdom of installing wind turbines near North American flyways, especially along the Great Lakes shoreline or out into the water. Birding is one of North America’s fastest-growing hobbies. Ontario’s Pelee Island is developing its economy around it while northern Ohio eco-tourism types promote Lake Erie’s islands.

People don’t need a catastrophe to feel a bit defensive about their sense of home.

Look at the mercury, lead, smog, carbon dioxide and other pollutants spewed from coal-fired power plants. It’s a legal assault on the environment, allowed by government permit, but an assault just the same.

Look at the mercury, lead, smog, carbon dioxide and other pollutants spewed from coal-fired power plants. It’s a legal assault on the environment, allowed by government permit, but an assault just the same.

Even military leaders have declared that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that cause climate change threaten national security – that is, our sense of home.

How quickly will cleaner alternatives be developed and what role will the Great Lakes region play in bringing them to the market?

A lot of questions remain, especially with projects such as FirstEnergy Corp.’s decision to abandon plans for a biomass facility at its R.E. Burger power plant in Shadyside, Ohio, along the Ohio River. FirstEnergy, one of the nation’s largest utilities, had planned to come into compliance for air emissions by converting two units from coal to wood. Environmentalists questioned where all of the wood would come from.

So now, companies such as Arizona-based First Solar continue to prosper in the Great Lakes region. It is one of the few in the Toledo area that has significantly expanded it workforce recently – yet most of its business still goes to Germany.

Michigan-based DTE Energy is investing some $100 million into its SolarCurrents program. It seeks customers for 20-year commitments to solar systems owned, installed, operated and maintained by the utility.

One of the more promising ideas could be in Montreal, where federal and provincial governments invested some $6 million this summer on underwater turbines to turn the St. Lawrence River’s current into electricity. If all goes well with a test run ending in June, Groupe RSW Inc, will continue on with an $18 million project.

Safeguarding a regional identity

The Great Lakes region’s 40 million people benefit from all of the fresh water, shipping, recreation and tourism the lakes provide.

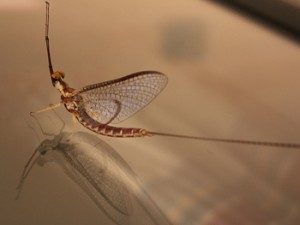

Water sentinel: Before taking this winged form, mayflies live burrowed in lake sediment. Photo: MJ Swart, via flickr

They may not own a sailboat or go scuba diving, but those lakes contribute to their regional identity.

Biologists bemoan the loss of any species. Yet certain ones strike a chord with us.

Mayflies are a sentinel of Lake Erie water quality. The Karner blue butterfly is a symbol of northwest Ohio’s globally distinctive Oak Openings region.

The Lake Erie water snake is neither cute nor cuddly, but enough of us finally stood up for it because our Lake Erie islands are the only places on Earth it exists.

Consider the American bald eagle. What would have happened to our sense of home if we had allowed our national symbol to vanish from the Lower 48?

We look to nature for hope, inspiration, relief. We may not hike, bike, fish or camp. But like a good opera troupe or symphony, we want to know it’s there.

“I don’t believe nature is God, but I do believe it is the way God communicates with us,” Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., has said at the end of various speeches.

The assault can come from simple, everyday pollution – so small and subtle it practically goes unnoticed.

Or as a catastrophe, such as an oil spill.

You may encounter a killer tornado. A makeshift flagpole. Old Glory flapping in the breeze.

But sometimes, you’ve gotta just stake your claim in home.

Tom Henry covers the environment for The (Toledo) Blade and writes an occasional column for Great Lakes Echo.

Brilliant.

Our sense of home is where the heart is, and where there is heart, there is the hope of courage and action.

Great persepective. I would have wished that the article included the disaster at Grand Lake St. Marys(GLSM), Ohio’s largest inland lake, which last summer essentially died. GLSM had signs telling boaters to stay out of the water and don’t touch the yucky green water. People got sick, animals died and the local economy dependent ont the summer season plumetted. GLSM is a warning for Lake Erie’s grouing algae/nutrient problem.

Failing to reduce nutrients going into Lake Erie will result in grave harm to people, animals, fish, drinking water and the Lake Erie economy.