U.S. Forest Service researchers are calling on the once-abundant American elm as part of an effort to restore streams in Finger Lakes National Forest.

Jean Lodge and research technician John Cody measuring an elm planted as a pilot test in 2013. Image: Finger Lakes National Forest

They expect the Burdett, New York, project to improve soil and water quality by reintroducing native trees — American elm, bur oak and silver maple — along Finger Lakes’ streams.

“We want to accelerate the changeover from the grassland community to a forest community,” said Jean Lodge, a botanist who studies fungi for the Forest Service.

Parts of the 16,259-acre forest were invaded by nitrogen-rich grasses and non-native shrubs, including the voracious multiflora rose and common buckthorn.

Along Finger Lakes’ Hencoop and Bolter Creeks, these woody shrubs had crowded out native trees and supported grass growth.

“The streams have a multitude of issues preventing a healthy forest canopy from becoming established,” said Leila Pinchot, a research ecologist for the Forest Service.

Without a forest canopy, grasses have no competition for light and overrun the streamside, she said. The competition between trees, grasses and invasives starts underground.

Grasses grow fast, die fast and decompose fast, Lodge said.

They support an ecosystem that’s different from forests. It’s a bacteria-dominated environment high in nutrients but also high in nitrogen.

And that’s perfect for the streamside invaders like multiflora rose, Pinchot said.

Multifora rose. Image: G.A. Cooper, USDA

It’s a cycle — nitrogen supports the growth of grasses and the grasses return a water-soluble form of nitrogen into streams and lakes.

“Nitrogen in the stream will cause algal blooms,” Lodge said. “Dead algae decompose and suck up the oxygen in a stream, leaving invertebrates without oxygen and fish without food.”

Researchers hope the physical and chemical removal of invasive plants, including a 7-foot multiflora rose, and the establishment of American elm and other native trees will reverse this process.

But not without help.

Scientists are mulching near trees to keep the grasses from outcompeting the trees for nutrients.

Jean Lodge spreads a mulch treatment for a newly planted seedling. Image: Finger Lakes National Forest

“Hopefully, mulch can reduce competition above and below ground, giving the trees a chance to grow more quickly in the initial stages,” Lodge said.

Quick growth means more sun for the trees and less for the grasses or invasive shrubs. It also means more shade for the streams, which lowers the water temperature for fish.

The deep roots of mature elms and mulch also tie up some of the nitrogen polluting streams, Lodge said. Mulch will even keep moisture in the soil during the summer.

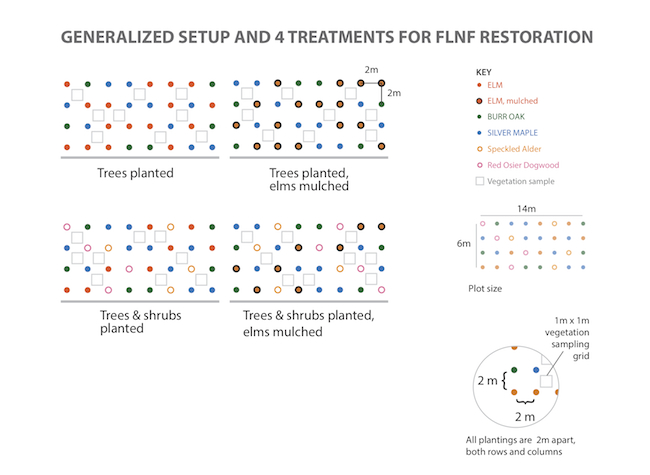

Half of the elms reintroduced by scientists have half-meter mulch rings around them. The other half is without mulch — part of a related experiment testing vegetation growth.

Oaks join half of the 240 elms, scattered in Finger Lakes by scientists within the stream sites, Pinchot said. Maples and native wetland shrubs are also in half the mix.

Preliminary plot setup for the Finger Lakes stream restoration project. Actual research plots are double the size indicated. Image: Vince D’Amico, Finger Lakes National Forest

Forested stream banks make for healthy streams and provide a good option for filtering out nitrogen, Lodge said. Forests are dominated by fungi, unlike grasslands and pastures, that help hold nutrients in the soil.

But scientists will have to wait two to three years to start seeing results.

“By then, some of the mulch starts getting incorporated into the top soil layer, where microorganisms feed on the available carbon and remove excess nitrogen from the soil to decompose the mulch,” Lodge said.

For now, the 640 total tree seedlings, provided by local New York seed sources, are soaking up the rain.

In further hopes for restoration, all elms were bred to better resist Dutch elm disease, a fungal disease that wiped out millions of urban and forest elms. Researchers are monitoring the seedlings’ response to local stressors, like fungal disease or plant invasion.

“We’re working with groups in New England and parts of the Midwest to breed in the Dutch-elm tolerance, creating new locally adapted trees,” said Pinchot, who’s based in Ohio with one of the breeding research groups.

This summer, scientists will continue monitoring seedling and grass growth.

“But we’re not just looking at the trees we’re planting. We’re looking at how the trees will impact insect diversity, how insects will impact birds and how the soil-vegetation dynamic changes over time,” she said.

Monitoring will continue every year.

A healthy stream system supports diverse flora and fauna, Pinchot said. “It will reduce sedimentation, it will filter pollutants and create habitat. This is what we’re looking for.”

In 2018, U.S. Forest Service scientists will continue stream restoration and monitoring and plant another hopeful addition — the endangered, cut-leaved toothwort, a weedy perennial in the mustard family. The herb could also benefit from the habitat created by mulching.