Community support for an uncommon restoration project saved the historical Fort Piqua Hotel from demolition. Photo: Bob Graeser

Editors note: This is part of a series of stories about innovative ways of recycling abandoned urban land and property in the Great Lakes region.

By Anne O’Dell

The Fort Piqua Hotel opened its doors to three U.S. presidents – William Taft, Theodore Roosevelt and Warren Harding. It hosted rallies for the Women’s Suffrage Movement and the Prohibition Movement. And it staged sit-ins for the National Civil Rights movement.

That history is what prompted Ohio officials to save it instead of demolish it.

“It has such a rich history, it would’ve been a shame to knock it down,” said Valerie Montoya, a specialist in the Ohio Urban Development Division, an agency that restores contaminated land known as brownfields.

In Ohio, 90 percent of brownfield sites receiving state grants are demolished instead of revitalized, making the Fort Piqua Hotel restoration unusual. In 2006, the crumbling hotel received a $1.3 million grant from the Clean Ohio Fund to spark one of the state’s largest renovation projects for a small town.

What also makes it unusual is that the rest of the $21 million needed for the project was raised from diverse sources, including liquor bonds and a citizen fundraiser. Ohio officials said the project size is enormous for a town so small. Piqua, located north of Dayton, has 20,000 residents.

“It’s phenomenal that they did this,” said Mark Lundine, urban revitalization coordinator for the urban development division. “It’s a 20,000 person town that did a $21 million renovation. That’s huge.”

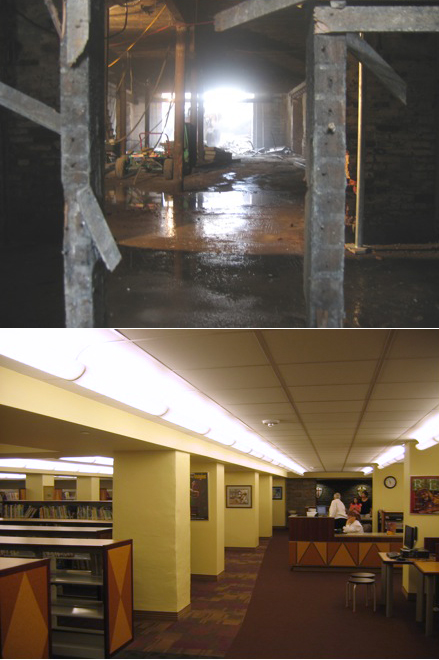

Saftey issues once made the building unusable. Now it's home to the Piqua Library. Photo: Bob Graeser

Although the old hotel now functions as a library, restaurant, café and special events center, the structure retains as much of its original architecture as possible.

“A lot of what you see is the same way it was when it was a hotel,” said Cindy Holtzapple, Piqua assistant manager. “The ballroom, foyer, restaurant were kept the same. Its use is as close to what it was previously used for as it can be.”

Built in 1891, the hotel was privately owned and operated for most of its life. Before restoration It was riddled with asbestos, lead paint, chemical contamination, cracked walls, broken ceilings and dangerous floorboards, said Vlad Cica, an engineer in the Ohio EPA brownfield remediation section. Cica said the problems were caused by dry cleaning operations in the basement, original building materials and 10 years of neglect when the hotel wasn’t operational.

“We couldn’t continue to maintain it because of safety issues,” said Holtzapple. “It would be demolished if something else couldn’t be done.”

In early 2000, Piqua officials surveyed the town to find out what citizens wanted done to the city. Renovation of the Fort Piqua Hotel topped the list, said Holtzapple.

Then, in 2004, the owners looked to restore the old hotel but the repairs were too expensive for them to do it. They sought help from economic developers who had seen other cities use the New Markets Tax Credit Program, a federal program that began in 2000.

Although, Piqua had been late to use the tax credit compared to cities in other states, it was one of the first communities in Ohio to employ it said Lundine.

“Being a small town, they were fairly innovative in using the New Markets Program in Ohio,” said Lundine. “Not many people had done it before because (the programs) were not in existence.”

The New Markets Tax Credit Program was one of nine sources of funds used to restore the hotel, said Lundine. City officials said the entire restoration cost more than $21 million, paid by loans, federal and state tax credits, a state clean up grant and private donations.

A community effort

Photo: Bob Graeser

The project almost was killed when the Clean Ohio Fund threatened to take away $1.3 million it had committed to the project. Cica said the town had been accumulating the funds, but it was taking too long and the grant holders couldn’t wait any longer.

“They needed a lot of money to redo the building,” said Cica. “We were only a small piece of the financial pie and we can only set aside money up to a certain point.”

Although the city had a majority of the funds, it wasn’t enough, and the Clean Ohio Fund issued a deadline for the rest. The city challenged its citizens to raise $2.5 million within a 10-day span.

During those 10 days, nine citizens donated the $2.5 million to secure the project. Jim and Connie Brown donated more than $1 million of personal funds, more than any other donor, said Jim Oda, director of the Piqua library.

“Mr, Brown believed that renovating the hotel was a centerpiece for the community,” said Oda. “And that the community could build out around it.”

Holtzapple said the other donors wished to remain anonymous, but she said she believed they donated because it was a multi-functional space.

“I think they were endeared to the fact that it would be used by many generations,” she said. “It wasn’t like the uses were one dimensional, there would something for different ages.”

The site almost tripled in traffic flow, going from 50,000 to 148,000 people a year, said Oda. That’s because the space allowed the library to put on programs and host clubs and presentations that couldn’t be done before.

Lundine emphasized the work the city took on to get it done, and the people who did the renovations: “It’s because people cared about the building and cared about the results. It’s good people who made this project happen.”

A historical landmark

The old hotel now functions as a library, restaurant, café and special events center. The structure retains as much of its original architecture as possible. Photo: Bob Graeser

The Romanesque building is 80,000 square feet and stands at the heart of Piqua. The sandstone exterior has elaborate carvings and gargoyle statues. It was a modern expression of architecture at the time of construction, said Barbara Powers, head of inventory of registration department in the Ohio Historic Preservation Office.

“The building is central to our community,” said Oda. “It is such a iconic building.”

When the city initially took on the project, Oda said there was a lot of debate about what it would house. Among the suggestions: a hotel with a helicopter pad. But the town decided to make it home to the public library. The library also operates the Piqua Historical Museum, which is fitting for a site with so much history, said Oda.

“It’s one of those things where it isn’t just a big building,” said Oda. “It’s historic for our town too.”

In 1947 the local chapter of the NAACP held a sit-in in the Bus Stop Restaurant, the restaurant inside the hotel, to protest segregated seating.

“It was the first restaurant to do it, and began the movement in the whole community,” Oda said. “It’s amazing to think it was done almost 20 years before the rest of country did it.”

The Piqua Anti-Saloon League also hosted rallies in the hotel. The organization began its campaign in 1894 in favor of prohibition that sparked a movement throughout the town, said Oda. But when prohibition ended, the hotel was also the first building in the community to open a bar and serve alcohol to its citizens.

“You can never replace and rebuild a building like this now,” Holtzapple said.

The building opened to the city in October of 2008, two years after initial remediation began. Holtzapple said watching people exploring the building was one of the best parts of the project.

One of her favorite memories from the opening day was when a grandmother and her two granddaughters walked through the foyer and one of the girls stopped and said, “I can start reading in the basement and have my wedding on the fourth floor.”

“It was heartening to see,” Holtzapple said, “knowing this building was going to serve generations to come.”

More from this series:

- Great Lakes cities recycle brownfields into economic hope

- Buffalo brownfields link past industry to hope

-

Solar power transforms a Chicago brownfield into a shining brightfield

-

Officials hope former truck factory helps make Michigan a movie star

- Federal loan brings employment hope to Wisconsin brownfields

- Detroit businessman proposes large scale commercial farm to struggling city