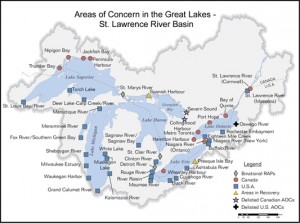

Forty-three Great Lakes toxic hot spots were identified by the U.S. and Canada as Areas of Concern. Click for EPA

Editors note: Congress is considering a $475 million appropriation for Great Lakes cleanup. This story is part of an occasional look at proposals for spending it. Weigh in on this and other ideas on Echo’s Great Lakes Restoration Initiative forum. Other stories.

By Andrew McGlashen

amcglashen@gmail.com

Great Lakes Echo

July 31, 2009

A plan to spend $147 million to restore Great Lakes toxic hotspots is inspiring cautious optimism among those involved in a long and often frustrating cleanup process.

Nearly a third of the $475 million for a Great Lakes Restoration Initiative in President Barack Obama’s 2010 budget targets cleanup at the remaining 30 Areas of Concern in the United States. They include rivers, bays and estuaries where pollution has caused fish tumors, beach closings, restrictions on dredging due to chemical-laced sediment, degraded fish and wildlife, added costs to agriculture and industry and harmful algae blooms.

“There has never been this amount (for cleanup) since the program started,” said Vicki Thomas, an administrator at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Great Lakes National Program Office. “I think this is a tremendous opportunity, and a lot can get done. There’s a lot of pent-up demand.”

The initiative has to be approved by Congress

A water-quality pact with Canada designated 43 Areas of Concern — often called AOCs – more than two decades ago. Since then, only two sites in Canada and one in the United States — New York’s Oswego River – have been restored.

How plan targets U.S. AOCs:

- The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would get a million-dollar boost to use computer models to help decide how best to prevent soil erosion and keep pollution out of the lakes’ tributaries.

- The same agency would get another $7 million to dredge New York’s Buffalo River and $3 million to help other communities plan the dredging of contaminated sediment, according to Corps engineer Jan Miller.

- The EPA would get nearly $23 million for eliminating beach closings, fish advisories and other impairments, and to restore wildlife habitat in those areas.

- A National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration database that helps monitor cleanup efforts stands to gain $1.75 million.

- And the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is in line for $4 million to restore habitat in Areas of Concern, and to develop the best plan to secure the toxic sediment on Grassy Island where dredged material is stored in the Detroit River.

Agency representatives and members of local advisory groups hope that the initiative shifts cleanups into higher gear. Those from Michigan are meeting Tuesday in East Lansing to plan how best to tap the funds.

Funding can’t meet entire need

“For projects like habitat restoration and improving water quality, it’s a good way to work toward those goals,” said Mary Bohling, who represents the Detroit River on Michigan’s statewide council on the areas of concern. “It won’t be enough to do everything that needs to get done, but it’s a start.”

The plan offers “a lot of opportunity to do good things,” said Rick Hobrla, manager of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality’s areas of concern program. “But there are probably some agency pet projects included that might not lead as much as we’d like to on-the-ground projects.”

Hobrla declined to give examples, but said he’d “be surprised if there’s not some in there.”

Studies or cleanup?

Some observers of the restoration process have urged agencies to spend the money on cleanups instead of studies. (Related poll.) But program managers defend the way the proposal allots the AOC funds.

“We want to keep the bundles of money broad, because each area of concern is different,” said the EPA’s Thomas. “Not everything will be shovel-in-the-ground. We try to put as much of the money into on-the-ground stuff as we can, but we have to do monitoring. We have to report results and be accountable.”

Amy DeWeerd, a Fish and Wildlife Service biologist and liaison to EPA, said she understands why people living near contaminated areas are frustrated when money is spent on studies and models instead of cleanup. She urged patience.

“These projects are very, very expensive,” she said. “We want to do it in the right way, so we don’t have to go back out there in a couple decades.”

Local funding requirement may be a hurdle

Hobrla said the cost-sharing requirement is a possible impediment. Under the Great Lakes Legacy Act, which sets aside funds for dredging contaminated sediment, a non-federal entity must pick up at least 35 percent of the tab for a cleanup. The Army Corps of Engineers has a similar requirement for disposal of sediment.

“That’s going to be a big concern, because Michigan and other states in the region have big budget problems,” Hobrla said.

Cost-sharing is required by law. Changing it isn’t part of the plan, Thomas said.

“The big message,” she said, “is that there’s finally money to clean up the Areas of Concern.”