Ken Cameron, director of the UW-Madison Herbarium, examines purple loosestrife, an invasive plant that will be digitized to aid identification and track its spread. Image: David Tennenbaum

Great Lakes researchers are building a time machine to help fight freshwater invasive species.

The project will let them navigate through a 150-year historical collection of plants and animals largely hidden among the storerooms of Great Lakes museums.

A $2.5 million federal grant will help their collections move from cupboards and shelves to a computer database through a process called digitization. Physical plant and animal specimens will be labeled and photographed for online access.

A cooperative of 20 universities and museums bypass the need of research staff to spend hours in a collection room pulling samples of North American fish, plants and mollusks.

Laura Halverson Monahan, curator of the UW-Madison Zoological Museum, holds a jar containing a common carp. Samples like this are moved from shelf to computer using the digitization process. Image: David Tennenbaum

Instead, the project will allow online access to over 1.7 million specimens, including 2,500 species, said Ken Cameron, who is leading the project and is director of the Wisconsin State Herbarium.

The digital collection will focus on Great Lakes non-native species but will include all species previously collected in North America.

These include species seen as threats and relatives of species which have already caused serious ecological harm, said Cameron.

The database will allow people to distinguish between similar looking species, like the Eurasian watermilfoil and other native milfoils, said Andrew Hipp, the project’s outreach coordinator. A Great Lakes invasive, the Eurasian milfoil invades freshwater quickly, outcompeting native freshwater plants.

But the project’s main beneficiaries are researchers.

They will be able to identify a species’ initial foothold and the direction of its spread. This helps researchers document patterns of invasion, contributing to future management of potentially threatening species.

For instance, researchers can find an invasive species like purple loosestrife and pinpoint where the wetland perennial was found before 1950. When compared to all known specimens from 1950 to 1980, they can begin to see the direction of spread.

Digitizing images of plants is straightforward, Cameron said. They are flattened on sheets of paper, placed on a light box and photographed from above.

Three-dimensional objects like this fish will be added to the digital collection. Image: The Field Museum

The challenge comes with three-dimensional objects like fish, which are generally preserved in jars of alcohol. These jars contain up to 50 specimens, including males, females, juveniles and adults, he said.

Cameron is working with museum partners to standardize the procedure, especially animal specimens which must be photographed from several angles.

A color card and metric ruler are added to digitized specimens for accurate comparison. Image: UW-Madison Herbarium

He advocates that museum officials digitize each image with a metric ruler and color card to account for size and the resolution difference on computer screens.

This procedure also includes geo-referencing — which provides the location of where the specimen was collected.

It requires computer software and bit of human patience. But it is important because it allows researchers to identify where the species was introduced and where it’s moved.

Cameron says the project’s focus is maintaining the integrity of the historical record.

“We’re like a time machine in that we have records going back 150 years, tracking species through time and space, which in terms of invasives can be very important,” he said.

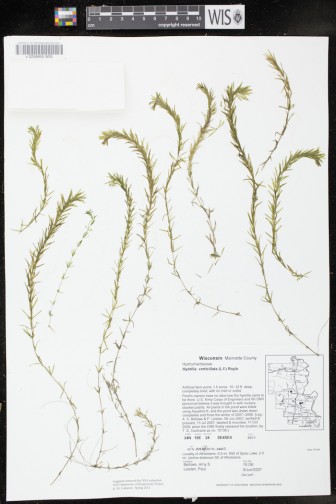

This digitized hydrilla, an aquatic invasive, will be added to the online collection. Image: UW-Madison Herbarium

While no new specimens will be collected or photographed, the digital record will verify reports of where they are found.

“Often times reports of occurrences are not backed up by a physical voucher or specimen, and that’s what we do in these museums; we preserve the actual occurrence, not just a rumor,” Cameron said.

The digital collections share data collected by state agencies and a database operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“The main objective is getting specimen data to the public — providing a shared data portal that extends this resource to professional users and students and especially to those outside the research spectrum,” said Hipp.

Hipp is developing curriculum for K-12 teachers that will allow students to use images to learn about invasives.

But the digital database also supplements research.

For example, geo-referenced images in the database can be tied to a historical record that might suggest how species physically changed over time, said Rochelle Sturtevant, a Michigan Sea Grant extension educator.

Invasive species and their close cousins will be added to the national database called Integrated Digitized Biocollections, otherwise known as iDigbio.

Sturtevant said, “If it was only about getting a hold of species’ pictures, one would have to question the value of the project. But it’s in the comparison of species over time and location that we begin to see the value. We no longer have to dig through background collections — we’ve provided open access.”