Listen to the story here…

Karen Schaefer is an Ohio freelance journalist and independent radio producer.

To see an EPA report on your drinking water quality, click here.

By Karen Schaefer

ANCHOR INTRO: Unless you have a private well, wherever you live in the Great Lakes, you’re probably using tap water to wash dishes, bathe, even make your morning coffee. Most U.S. public drinking water is safe — certainly a lot safer than it is in countries where water treatment may still be in the Dark Ages. But as independent producer Karen Schaefer reports, keeping up that high standard is becoming a lot more expensive.

SCHAEFER: There was a time — not that long ago — when typhoid outbreaks, like those that killed thousands in Haiti after the hurricane, were also killing residents in Cleveland. In 1903, nearly five-hundred people died from unsafe drinking water. The last case was in 1935.

ALEX MARGEVICIUS: Chlorine has been one of the biggest and most major advances in human health in the history of mankind, I would argue.

SCHAEFER: Alex Margevicius is Cleveland’s Water Commissioner. He’s standing in a corridor at the Baldwin Water Treatment Plant on Cleveland’s east side. It’s one of the city’s oldest water treatment facilities, built in 1925. He says Cleveland started adding disinfectants early on.

MARGEVICIUS: We added chlorine in 1912, because we were having cholera and typhoid outbreaks. And chlorine was the first thing that we did to make sure we had better water.

Old water treatment controls have been replaced by computers that constantly monitor water quality. Photo: Karen Schaefer

SCHAEFER: Since then, public water treatment has come a long way. Once a year, Cleveland opens one of its water treatment plants to the public. Baldwin plant manager Frank Woyma, who’s worked for the city water department since 1991, says for many visitors, it’s an eye-opening experience.

WOYMA: Most people are just amazed at what it takes to make drinking water.

SCHAEFER: The process starts with water from Lake Erie, pumped from one of four water cribs located several miles off-shore. The first treatment step is to siphon the water into huge underground settling tanks treated with alum, to sweep out larger sediments. Then it’s sent through cleaning filters, made of crushed coal and sand, that remove the finer particles.

WOYMA: At 55-Million gallons of pumpage a day, it takes about 8-hours for a drop of water to get from one end to the other.

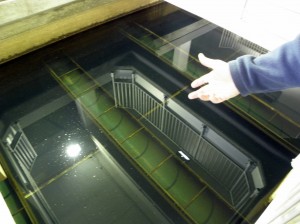

After settling pools, water is slowly filtered through sand and crushed coal to remove fine particles. Photo: Karen Schaefer

SCHAEFER: The final process is to add chemicals that disinfect the water, to be sure there’s no lingering bacteria that could make people sick. It’s a practice all water treatment plants follow. Even so, in1993, an outbreak in Milwaukee of the bacteria cryptosporidium killed more than a hundred people. Alex Margevicius says it was a wake-up call to the industry.

MARGEVICIUS: The US EPA came under a lot of criticism. You know, you’ve got all these rules and still something happened. People died. So the US EPA and the water industry and American Waterworks Associations said, can we do better.

SCHAEFER: The safety of tap water in Cleveland and many other Great Lakes cities now exceeds federal drinking water standards. By law, those federal standards are updated every six years. But there’s a new class of contaminants under review. Trace amounts of pesticides, prescription drugs, and consumer products like shampoo and fragrances are showing up in water across the U.S. Gabriel Eckstein is a law professor at Texas Weslyan University.

ECKSTEIN: Science suggests that aquatic species are being harmed.

Karen Schaefer’s series on [Northeast Ohio/Great Lakes] water quality – Drink, Fish, Swim — is supported by a grant from the Burning River Foundation.