By Mia Litzenberg

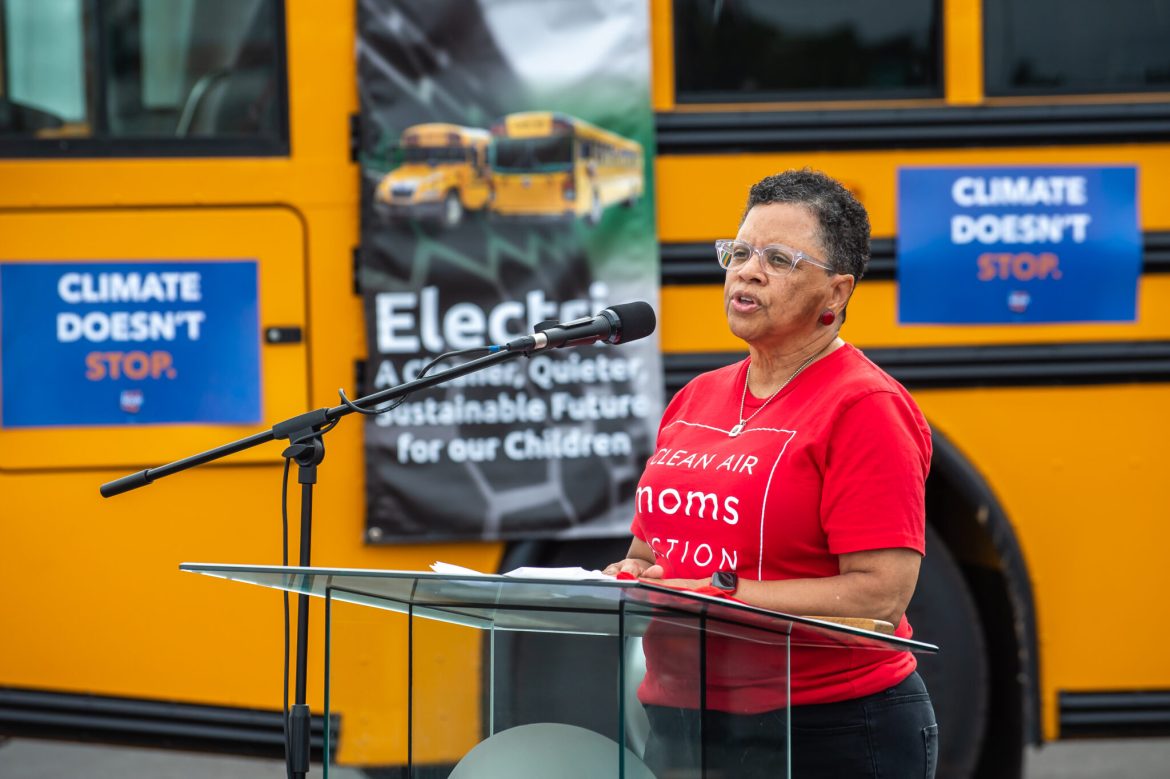

Moms Clean Air Force demonstrates an electric school bus in front of a manufacturing facility as a part of its national Let’s Get Rolling Tour in 202. Courtesy photo

In the Detroit area, people experience unsafe levels of particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and ozone in the air they breathe. These pollutants are blamed for adverse health effects such as heart disease, respiratory issues and cancer.

The University of Michigan is part of an ongoing Detroit research partnership, Community Action to Promote Healthy Environments (CAPHE). CAPHE identifies sources of air pollution, measures its impact on residents and empowers the community to take action.

CAPHE found that outdoor air pollution has caused people to miss a total of 500,000 days of work and 990,000 days of school. Over 24,000 students in Detroit attend a school within 200 meters (219 yards) of a major roadway. This falls within a distance considered to have peak air pollutant concentrations. The economic value of health impacts caused by air pollution in the Detroit area alone is $7.3 billion, annually.

However, outdoor air pollution was not the only factor that contributed to this staggering cost. Indoor air quality can be directly affected by pollutants that originated outside, on top of the numerous air pollutants that originate inside.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, indoor air can be more polluted than outdoor air in the biggest, most industrial cities. With Americans spending 90% of their time inside where air pollutant concentrations can be two to five times higher, seeking refuge indoors may actually be posing greater health risks.

While ventilating a building can dilute indoor air pollution, it may allow outdoor air pollutants to enter. Outdoor gas pollutants like ozone can cause a chemical reaction with indoor building materials, releasing toxic byproducts.

Since Americans spend most of their days indoors, a 2012 EPA study attributes an annual 130,000 premature deaths from fine particulate matter (PM2.5) to the pollutant’s ability to cross into indoor environments.

For someone waiting behind bars for months or years, sometimes before conviction, the inescapable sentence is the irreversible health impact of indoor air pollution.

Ohio’s Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland, faces one of the highest lead poisoning rates in the country. This often happens through soil contamination from aging housing stock. Lead exposure there has reached double the amount of people as the Flint Water Crisis. However, lead exposure does not end with direct soil contact.

Human activity, including the construction of Cuyahoga County’s jail, can release lead so that it becomes an airborne pollutant. The county’s long-abandoned Rockefeller oil refinery is now a shipping container storage yard and the origin of airborne carcinogenic chemicals, like benzene. This comes from certain types of smoke, like from volcanoes and forest fires, and gasoline and cigarettes. The site also produces excess potent greenhouse gasses like methane that comes from fossil fuel emissions and decomposition of landfill waste.

The Cleveland Division of Air Quality (CDAQ) recently launched the Community Leveraged Expanded Air Network in Cleveland (CLEANinCLE) project. The goal is to use community input to establish the sites of 30 new air monitors.

“This is a way to help understand where residents feel there are problems,” said the chief of air pollution outreach at the Cleveland Department of Public Health, Christina Yoka.

One of the main areas of focus is the “Cleveland Crescent,” which extends through the northeast, central and southeast parts of the city. It also follows the city’s historic redlining map. Residents tend to be people of color in lower-income communities.

“These residents are dealing with air pollution concerns, but then they’re also dealing with the multitude of other stressors in their environment, and other health risks,” said Yoka. “Air pollution is going to make existing health conditions worse.”

In some Cleveland neighborhoods, the pediatric asthma rates reach 21% or more, compared to the national rate of 6.5%.

The data collected by the air monitors will be displayed on a public data dashboard that reports the live Air Quality Index– a measure of the air pollution level ranging from 0 to 500 with six categories of concern. This will help the CDAQ exercise its regulatory authority over things like a facility that doesn’t have a permit or that’s operating outside of the terms of its permit.

A mobile monitoring shelter will also be put into use this summer in Cleveland. This is a more highly specialized piece of equipment used at federally regulated monitoring sites, which stays at a different location every year to collect seasonal data.

However, air pollution poses yet a greater challenge: It cannot be contained to the location of its source. Alexandra Zissu discovered this after moving her family north from New York City to the Hudson Valley.

“I was there for 40 years and then I fled,” said Zissu. She became involved with the New York chapter of a national organization, Moms Clean Air Force, over a decade ago.

Zissu grew up in New York City near the West Side Highway. She discovered her interest in environmental health issues when she became pregnant with her first child. During her second pregnancy, she began to tie her knowledge of airborne pollutants to children’s health.

“I learned that children are uniquely vulnerable to environmental chemicals, especially because their lungs aren’t fully formed yet,” said Zissu.

She said she became increasingly aware of air pollutants from transportation sources along the highway, so she moved.

This diagram shows the increasing severity of health complications caused by air pollution. A greater proportion of the U.S. population experiences effects that are less severe, while a smaller proportion experiences more severe effects. Date source: U.S. Environemntal Protection Agency

Ozone and particulate matter can be carried hundreds of miles from their source, meaning emissions cannot be contained within city or state borders.

The EPA distinguishes between two kinds of ozone. Stratospheric or “good” ozone is naturally occurring in the atmosphere and helps block ultraviolet rays from the sun. Tropospheric or “bad” ozone is created during a ground-level reaction between nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds in sunlight.

These pollutants come from sources like vehicles and power plants.

When tropospheric ozone enters the lungs, it causes a multitude of health issues including chest pain and exacerbates existing conditions like bronchitis, emphysema and asthma. Over time, constant exposure can scar lung tissue.

Like ozone, particulate matter has two main categorizations:

- Things like dust, pollen and mold are considered PM10 – particles with a 10-micrometer diameter or smaller.

- Combustion particles like sulfur dioxide, organic compounds like methane and metals like lead are considered PM2.5 – particles with a 2.5-micrometer diameter or smaller.

While PM10 can get deep into the lungs and even the bloodstream, PM2.5 poses a greater concern.

As a combustion particle, not only is sulfur dioxide a part of PM2.5, but it exists as a pollutant on its own. It is a gas that forms during coal, petroleum oil and diesel combustion. When inhaled, it compromises the respiratory system, contributing to chronic health conditions like asthma.

Similarly, nitrogen dioxide is a gas that forms during fossil fuel and wood combustion.

The American Lung Association found it could affect pregnancy and birth outcomes and increase risk of kidney and neurological damage. It was associated with autoimmune disorders and is more commonly known to inflame the lungs.

Nitrogen dioxide is a part of PM2.5 pollution and the chemical reaction that creates ozone.

CAPHE has pinpointed Detroit’s exposure to these air pollutants from point sources, like coal power plants, coke fuel for steel, cement industrial facilities, oil refinerie, and waste incinerators. The city also takes on air pollutants from vehicles, or mobile sources.

A study for the National Institute of Health revealed that 59% of indoor particulate matter during the winter and 84% of indoor particulate matter during the summer originated outdoors.

Indoor air pollution has been found to decrease workplace productivity and school performance.

The EPA says indoor filtration can supplement source control and ventilation with clean outdoor air, but cannot entirely remove air pollutants. The Clean Air Act regulates six major pollutants: carbon monoxide, ground-level ozone, lead, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide. However, wildfire smoke still flies under the radar.

CAPHE established the Environmental Health Research to Action (EHRA) initiative to empower youth in communities with heavy air pollution through environmental, health, and policy education. The two and a half week program prioritizes 16-to-18-year-olds.

“Most of us don’t learn that [environmental policy] in our K through 12,” said EHRA co-director Natalie Sampson. “I think we’re capable of learning.”

Although EHRA helps youth build their advocacy skills, Sampson disagrees with the narrative that today’s environmental and health issues are solely the younger generation’s burden.

The core mission of EHRA is to strengthen the intergenerational alliance against systemic air pollution. EHRA also offers environmental health and justice lesson plans through the lens of climate change to K-12 teachers.

In U.S. school systems, climate education addressing air pollution is required to be a part of the curriculum only in New Jersey and Connecticut.

Meanwhile, half of the 57.5 million students and employees in schools across the country are subject to indoor air pollution. They are the living, breathing examples of what is at stake if indoor air quality remains invisible.

Mia Litzenberg has an environmental reporting internship under the MSU Knight Center for Environmental Journalism’s diversity reporting partnership with the Mott News Collaborative. This story was produced for Great Lakes Now.