The cover of “A Private Wilderness: The Journals of Sigurd F. Olson.” Image: University of Minnesota Press

By Taylor Haelterman

A decade after the death of Sigurd F. Olson, his son found many of the famed author and conservationist’s journals in an unplugged refrigerator in the family home’s basement.

Olson, who died in 1982 produced the bestseller “The Singing Wilderness,” which propelled him into national fame in 1956, said Steffi O’Brien, the executive director of the Listening Point Foundation in Ely, Minnesota, which preserves Olson’s legacy and philosophy. He also helped shepherd some of the nation’s leading wilderness protection efforts.

“His main message was that the wilderness, natural places, are important to the human spirit. And he wanted to preserve that,” O’Brien said.

Most of Olson’s journals consist of disorganized loose-leaf paper that sometimes lacked dates. Editor David Backes sifted through all of Olson’s journal entries, a majority of which were from 1930 to 1941, to create “A Private Wilderness: The Journals of Sigurd F. Olson.” It will be available for $29.95 on June 1 from the University of Minnesota Press.

Olson grew up in Wisconsin and moved to Ely, Minnesota, where he taught at a high school and Ely Junior College. He was dean of the college from 1936 until 1947, when he started writing full-time, according to the Listening Point Foundation.

He was a noted conservationist, serving as president of the National Parks Association and the Wilderness Society and as advisor to the National Park Service and to the secretary of the Department of the Interior.

Unlike Olson, Backes is an organizer. He wrote a biography of Olson published in 1999, and that work made it easier to put this book together, he said. He had already organized and saved copies of the journals, knowing he would love to make a book about them someday.

“It’s truly a companion piece to the biography,” Backes said. “A biography tells the story of a person’s life using all of these different sources, and hopefully you get a really good sense of the person’s character through a biography. But, in this book, you get to see that character developing through his own perspective as it’s happening.”

Backes has been writing about Olson since college.

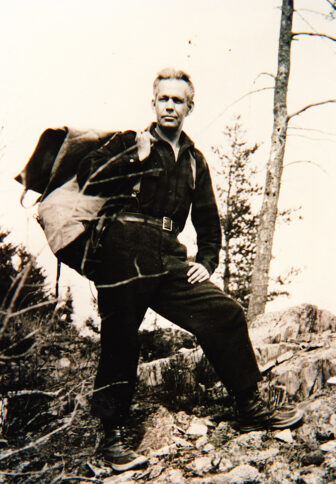

A promotional picture for Olson’s “America Out of Doors” column taken around 1941. Image: David Backes

He became a friend of the family after he wrote Olson in 1977, explaining he was considering dropping out of the University of Wisconsin because his grades dropped and he couldn’t pursue a degree in wildlife ecology and forestry.

After reading Olson’s book, “Reflections From the North Country,” he thought Olson might understand what he was going through.

To his surprise, Olson responded.

“He basically said, ‘Stay in school,’” Backes said. “Just the fact that he wrote and that it was encouraging, it helped me to stay in at a moment when I so easily could’ve dropped out.”

Backes took the advice and obtained a bachelor’s degree in continuing and vocational education, and a master’s in journalism.

Backes spent time as a journalism professor at the University of Wisconsin, following Olson’s example by encouraging struggling young people not to give up on their passions.

He said he hopes to continue spreading that message with the book by showing Olson’s internal struggle to follow his own passion for writing.

“In life, so many people give up,” Backes said. “We have a society that says ‘be all that you can be,’ but then really discourages you from doing it because ‘oh, that’s not really practical.’

Well, Sigurd and I believe that it’s not only practical but necessary.”

Readers may be surprised by how long and how often Olson struggled to become the full-time writer he wanted to be, the editor said. He often wrote about it in the journals, like when his wife, Elizabeth, suggests a divorce to set him free of his responsibility to the family so he could write.

When obtaining his master’s degree under the lead ecologist in the nation, Olson wrote, “I hate the very sound of the word ecology.”

And in the first chapter of the book, Olson writes “The way will be long and hard but I must follow or die. TO WRITE MORE BEAUTIFULLY THAN ANYONE ELSE ABOUT NATURE.”

Backes said his other goal with the book is to preserve Olson’s legacy. He did that by hardly editing the work, only correcting misspellings that were distracting and leaving incomplete sentences and Olson’s underlines and highlights.

He also left in the ampersands when they were used instead of the word “and” so readers know those sections were handwritten. Olson usually spelled out the word only when typing, Backes said.

Olson helped establish the U.S. wilderness preservation system, a wildlife refuge in Alaska, a national seashore in California and Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota, according to the Listening Point Foundation.

The Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, the National Wildlife Federation and the Izaak Walton League all recognized him for his work. In 1974, he received the John Burroughs Medal awarded to the best nature writers, illustrators and publishers.

O’Brien is confident Backes is the right person to edit the book.

“Knowing David, I know that he has spent so much time going through pretty much every single journal he could find, reading it, organizing it, making sure that whatever we get is the best picture that we could have of those journals,” she said.