Governor Snyder is hoping someone in the crowd knows the answer to stopping invasive carp.

By Talitha Tukura Pam

Imagine the governor of Michigan as a contestant on the game show, “Who wants to be a millionaire?”

The question: “How do you stop carp from invading the Great Lakes?”

Gov. Rick Snyder doesn’t know. He must decide to call an expert friend or ask the crowd. He chooses the crowd.

Good choice.

The everyday game show audience gives the right answer 91 percent of the time. The expert friend is right 65 percent of the time.

Michigan is offering $1 million to anyone who comes up with a new and innovative solution to prevent Asian carp from entering the Great Lakes. And unlike the game show, it’s not the contestant but a lucky crowd member who wins that $1 million prize.

What is at stake is a $7 billion fishing industry, water recreation generating about $38 billion in economic activity and the health of the world’s largest freshwater ecosystem.

“That makes $1 million spent on the challenge look petty,” said Joan Foreman, the communication secretary for the challenge.

Incentive begets innovation

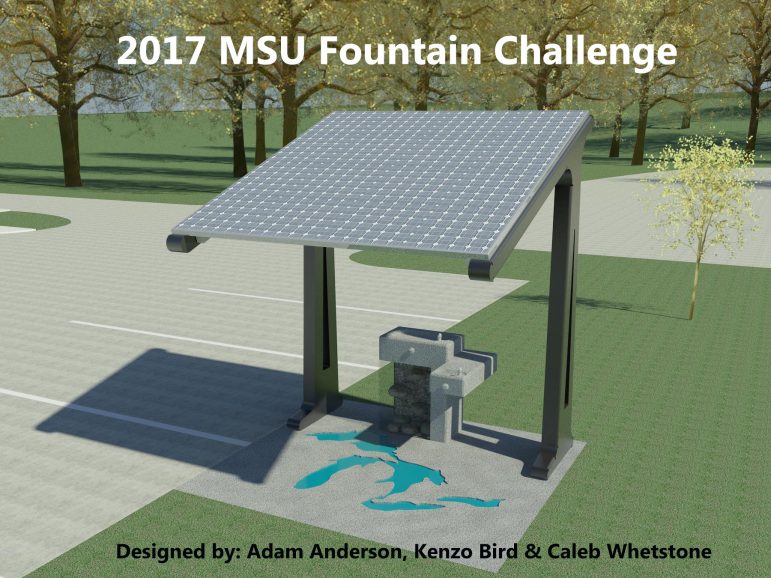

It’s also part of a trend in using cash incentives to solve resource problems. For instance, Michigan State University recently sponsored a challenge to redesign water fountains. The winning team won $15,000.

It’s also part of a trend in using cash incentives to solve resource problems. For instance, Michigan State University recently sponsored a challenge to redesign water fountains. The winning team won $15,000.

“The students are innovative and energetic and we were very excited to support student team learning and effort through problem solving,” said Joan Rose, an MSU international expert in water quality and public health safety.

Another example: The Michigan Design Council has sponsored contests for K-12 students to develop products to better enjoy the state’s water and winter.

“So far we’ve been quite successful and have had very unique and sophisticated solutions to huge problems,” said Jeff De Boer, the chair of the Michigan Design Council. “Based on that, I do not doubt that anybody can come up with successful and creative solutions for the carp problem.”

“We depend on experts to solve our problems and are swayed by intelligence, but many of our answers are found in the simplest places,” De Boer said.

To help organize the carp challenge, the state spent about $300,000, to hire the Massachusetts-based global crowdsourcing firm InnoCentive. The contest and its rules will be announced sometime in July and hosted on the InnoCentive website, Tanya Baker, the deputy press secretary to the governor, wrote in an email.

Since 2010, the federal government has spent more than $380 million battling invasive species like the Asian carp.

“Some of our biggest clients are the federal government and large corporations who look outside for ideas and talents to solve problems,” said John Elliot, the head of business development at InnoCentive.

“We have handled different challenges with the Bureau of Reclamation and the EPA so, we do have some experience with natural resource type challenges,” Elliot said.

NASA had been working on predicting solar flares for a long time and had consulted many experts, Elliot said. The agency launched a challenge and the problem was solved by a radio technician in New Hampshire. By posting the question to a crowd, NASA improved solar flare prediction by 80 percent, Elliot said.

The more the merrier

“Using a crowd is effective because you can literally tap a diverse global network of creative minds,” Elliot said.

The Roche pharmaceutical company ran a challenge with an incentive to solve a problem it had worked on for 15 years, he said. In less than 60 days it got two solutions that worked. The scope of the hundreds of submissions it received covered the entire scope of their work over 15 years.

“If you think about the resources spent in 15 years for this problem in comparison to using a crowd and solving it in two months, there’s return on investment,” Elliot said.

The “Wisdom of the Crowd” by James Surowiecki explains that under the right circumstances, groups are remarkably intelligent and often smarter than the smartest people in them.

“Crowd wisdom generated by the knowledge and observations of citizens has been valuable for documenting environmental change,” said Steve Gray, assistant professor in community sustainability at MSU.

In every crowd are insights, flashes of genius and ideas that will never be evident from job applications, resumes or consulting brochures, Gray said.

Crowd sources hinge on the model that every person is unique despite varying academic and career qualifications.

Neil Kane, director of the MSU undergraduate entrepreneurship program, agrees. “Any and everybody has the potential to solve a question,” he said.

Said De Boer: “We depend on experts to solve our problems and are swayed by intelligence but, many of our answers are found in the simplest places.”

The model is similar to XPrize which creates incentives for people to submit ideas that are then vetted by experts.

“An XPrize is usually applied to very difficult solutions,” Kane said. “So, it makes sense that it’s being used in this.”

Cracking the carp challenge

Researcher Brooke Vetter and tanks used to hold carp for sound study. Image: Brooke Vetter

If you’re up for the carp challenge, you might first check out what others have suggested:

- Sonar-equipped robo-kayaks

- Blasting carp with sound

- Creating dead zones with nitrogen bubbles

- Enlisting pelican power

- Using chemical repellents

- Turning up the juice on electrical barriers

More background is at the Michigan Department of Natural Resources website.

“It could be that the technologies and ideas that we have are not working,” said Foreman, the challenge’s communications secretary. “There are people that do other things that might look at the problem and say hey, this idea might work.”

Robo kayak that could use sonar to detect carp. Photo: Mike De Abreu

A unified competition by the Great Lakes states might have been a better approach, De Boer said. “The fact that it crosses state lines but is launched by the state of Michigan might be perceived differently by other Great Lakes states.

And finding that genius idea is only one side of the coin.

“Implementation will be difficult because that is when the hard work will have to start,” De Boer said.

Since the announcement, reaction has been mixed.

“I was hesitant about the plan because it seemed a little bit to me like the Michigan government was passing the responsibility of the issue on to the people of the state of

Pelicans scarfing down carp. Image: Bill Rudden

Michigan when we had agencies responsible for and funded for this situation,” said Tom Braum, a graduate student at Michigan State University studying fisheries and wildlife. “However, because of the risk to Michigan’s economy and Great Lakes ecology, I think that is a good idea to have as many people provide input as possible.”

Others are skeptical: “I think there is a slim to zero chance that competition could make any ecologically significant impact on the Asian carp population,” said Andy Deines a postdoctoral associate at MSU’s Center for System Integration and Sustainability. “The best that can be hoped for is garnering enough attention, and creating motivation for people to support other more effective, though expensive, invasive species prevention measures.”

This isn’t the first time that resource managers resorted to crowds to tackle an invasive species.

The Burmese python arrived in North America through the pet trade in 1970. So far, it has literally eaten its way through Florida’s Everglades, drastically changing the ecosystem.

Resource managers have incentivized crowd control of the Burmese python which is invasive in the Florida everglades. Image: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission teamed up with the Fish and Wildlife Foundation of Florida to launch the 2016 Python Challenge which was a follow-up to the 2013 competition. The competition was for groups and individuals to remove the Burmese python from the Everglades in return for cash prizes. The project’s website reports that the program created awareness of the problem and removed 106 pythons.

So, money may help.

And so, too, might a good bath.

It was at the public bath when Archimedes realized that the more his body sunk into the water, the more water he displaced and that water was an exact measure of his volume.

It was a discovery that enabled the king to check the purity of his gold.

Archimedes supposedly jumped from the bath and yelled, “Eureka!” as he ran through the streets.

Whether someone with a carp cure will do likewise is yet to be seen.