By Morgan Linn

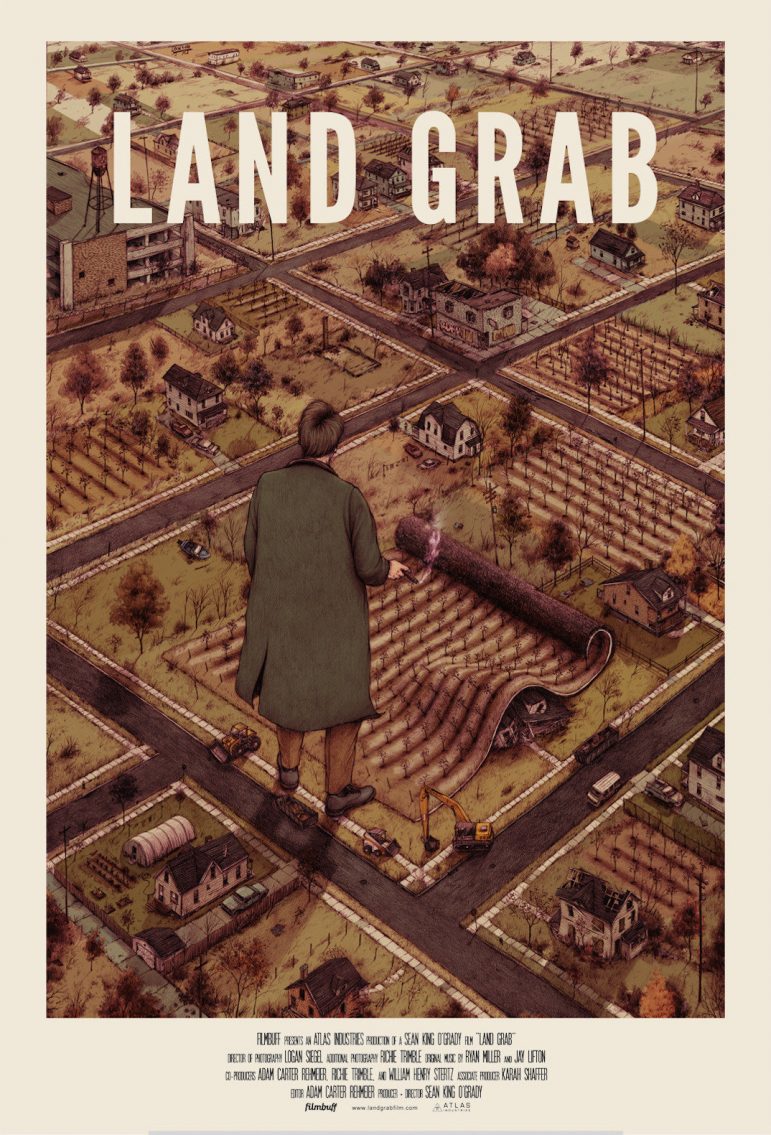

Land Grab poster.

Blight harms Detroit residents every day.

It lowers the perceived worth of a community and makes residents feel unsafe walking in their own neighborhood.

That’s why John Hantz, a finance mogul and long-time Detroit resident, decided to help replace that blight with the world’s largest urban farm.

He promised $30 million of his own money to renovate 10,000 acres of Detroit.

“It’s an investment in a livable neighborhood,” said Mike Score, the president of Hantz Farms, Hantz’s company.

But Hantz met unexpected resistance from some residents who saw the move not as charitable, but as a grab for land by a wealthy, white business executive.

Michigan State University recently hosted a screening of “Land Grab,” a documentary about the creation of Hantz Woodlands and the political uproar surrounding it. The Sustainable Michigan Endowed Project, Knight Center for Environmental Journalism and Department of Geography, Environment and Spatial Sciences sponsored the screening and discussion with Score and Sean O’Grady, the director and producer of the film.

O’Grady had heard about the controversy and wanted to find out why residents opposed a project that could benefit them. Previously he produced “In a World” and “Big Sur,” documentaries that came out in 2013.

The reason for the opposition boils down to a long history of broken promises in Detroit, according to the film.

Hantz’s plan to purchase land and improve it sounded a lot like projects proposed in the past that had failed, making Detroit residents hesitant to trust another “charitable” project.

Hantz would buy thousands of foreclosed lots from the city. Some neighbors worried about that redistribution. They didn’t want a wealthy, white man owning a large portion of the Eastside and profiting from it.

Some of them had applied to purchase lots that Hantz bought from the city, and were upset that they were no longer available.

So Hantz Farms offered to sell lots at a loss to residents, Score said.

Mike Score and Sean O’Grady. Image: Morgan Linn

“I insisted that at the beginning, for the first 60 days, the residents of Hantz Woodlands could buy the lots next to their homes,” he said. “We were paying $300 per lot and the neighbors could buy it for $200 a lot.”

Before being purchased by Hantz, the abandoned property wasn’t making any profit, said Sen. Bert Johnson, D-Detroit, during an interview in the film.

“We weren’t grabbing land, we were buying it,” Score said. Buying the land returned it to private ownership. Hantz now pays $180,000 a year in property taxes.

The company paid $7 million to renovate the land and hasn’t made any profit yet, Score said. And he has no plans to make money off of the land anytime soon.

“It’s not smart business,” Johnson said in the film. Hantz is “beautifying the community without incentive.”

Neighbors worried what would be produced on the land. The initial plan was to create an orchard, but residents worried rats would be attracted to fruit falling on the ground, Score said. So Hantz planted rows of hardwood trees instead.

After a four-and-a-half-year battle, the city council approved the project 5 to 4 in 2013, requiring that Hantz clear a certain number of lots within two years. Failure to meet the quota meant returning the land.

But in just a year, four workers cleared almost 2,000 blight-ridden lots, knocked down 56 dangerous buildings and planted more than 15,000 trees, Score said.

And property values jumped from $15,500 to $74,750 between 2009-2015, according to the film.

Hantz also “formed a family foundation and invested several hundred thousand dollars per year in the neighborhood schools,” Score said. “The Hantz Foundation has been plugging gaps in the educational system, so that in addition to the neighborhoods looking nicer, the schools start performing at a higher level.”

The change has greatly benefited the lives of residents, Score said.

“Our neighbors tell their families about how the neighborhood’s changed, and they have people who can’t believe it,” Score said. “They take a look around and they’re won over because they now see that their family has a better life.”

And the trees are eliminating areas for crime and dangerous wild dogs, he said. The neat rows of hardwood trees mean more open space and higher visibility.

“The habitat for people who are doing illegal activities is gone,” Score said. “Police came up and told us that now when they’re patrolling, they can sit three or four blocks away from a place where bad things are happening and they can patrol.”

The success has changed the minds of some former opponents.

“The most interesting one is André Speyve, who is on the city council and actually voted against the project,” O’Grady said. “He now says that if he could take back the vote, it’s probably something that he would do.”

The documentary also has had a positive effect.

A group of students from Detroit saw the movie and it changed their perspective, Score said. “They came into the movie thinking they wouldn’t like Hantz Woodlands, but after they saw the movie, they’re more supportive.”

For those who remain opposed, O’Grady said he hopes they feel their voices are represented and treated as valid by the film.

“I tried to be as objective as possible in terms of putting enough information out there from both sides,” he said. “What’s important to me is that people who are opponents can watch the film and they feel that their viewpoints are represented.”

O’Grady says he hopes the film generates discussion and gets a message of healthy skepticism across.

“It’s important to still be skeptical and to still wonder what people’s intentions are,” he said. But “you can’t be opposed to all progress.”

So what’s next for Hantz Farms and “Land Grab?”

The city had promised that Hantz Farms could buy an additional 180 acres at the same price as before if it met its initial goals.

The project exceeded those goals 11 months ahead of schedule in 2014, Score said.

That sale still hasn’t been finalized. If a deal on the new land isn’t reached by the end of the year, the company will take the issue to court, he said.

Instead of 180 acres, Hantz Farms is now requesting only 50 to avoid conflict, Score said.

“We want to finish what we started and make areas truly livable when we’re done,” he said.

Universities nationwide are screening the documentary as part of an educational tour. For upcoming screenings, click here. It will later be available on Netflix, Amazon and iTunes, O’Grady said.

There is potential for Detroit to be a model city for urban renewal. Many local people are working on creating a desirable place to live and many others are cheering for you. A city with neighborhoods consisting of homes, gardens, woodlots, small farms and shops powered by a local energy grid of wind and solar could be a dream come true city. Places designed on a human scale and containing natural features where people are out and about are relaxing to live in.