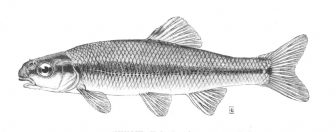

Blunt nose minnow. Image: wikimedia

By Josh Bender

The Grand Calumet River’s blunt nose minnows are recovering but still suffer greatly from intense industrial pollution of the Indiana river that flows into Lake Michigan near East Chicago, according to a recent study.

The population’s male to female ratio and the number of deformed fish are improving but remain concerning, according to the study published by Indiana University aquatic biologist Tom Simon and his then graduate student, Jacob Burskey. The study was published in the Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology.

The news isn’t all good. In fact, the stench of oil emerged from the fish when cutting them open to examine their internal organs for the study, Simon said.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Simon said. “How were these fish even surviving?”

For years the minnows suffered as heavy industry pounded the river and its denizens with industrial waste, Simon said.

It was among the dirtiest in the country, according to a 1990 Rolling Stone article that described a “river from hell’’ because pollution-induced heating caused steam to rise from it.

When Simon studied the minnows in 1998, about 97 percent were male. Most had blackened gonads and paper-thin livers, he said. A healthy population of the minnows normally tends to be more female than male.

Most of those he studied then suffered from physical deformities, including blindness and tumors.

The river has undergone extensive cleanup.

And the health of the minnows has improved. The 2016 study reports that 51.8 percent and 73.3 percent of the fish were male at two different sites collected in 2014. But two other sites were 42.5 percent and 43.3 percent male, a proportion typical of a healthy population, according to the 2016 report.

At two collection sites, 40.7 percent and 70 percent suffered from some form of deformity, tumor or other pollutant induced ailment, according to the 2016 report.

But almost all female fish examined were sterile or had damaged ovaries and 98.6 percent of fish, both male and female, still suffered from liver damage, according to the 2016 report.

Years of restoration work by the Environmental Protection Agency has helped the river’s wildlife recover, said Mark Loomis, an agency official helping oversee the restoration efforts.

Pollution once contaminated sediments deeper than 12 feet below some portions of the bed’s surface, Loomis said.

The cleanup work on the riverbed benefitted not only the sediment-dependent minnows. The bass and salmon that eat the minnows are making a return as well, he said.

After a century of absence, the banded killifish returned to the river, he said. “They feed off insects and the less toxic sediments are making it possible for these insects to live there.”

The river’s improvement should be met with cautious optimism, Simon said. In 2017, he and his team will return to the Grand Calumet to examine the minnows again. The minnows seen in the group’s more recent visits were quite young and had not experienced sustained exposure to the pollutants still present in the river.

While the resurgence among game fish is encouraging, the team observed many game fish were poisoned by over consumption of pollutant laden minnows, Simon said.

Another concern is the effect of pollutants on minnows drawn to the river by its abundance of shelter, growing number of female minnows and relatively low number of predators, he said. These new minnows can survive but the pollutants will still increase their likelihood of becoming sickly and sterile.

However, the durability demonstrated by gamefish population is making this a less pressing concern, he said. The predators will thin out the minnow numbers and make the river a less attractive destination for new arrivals.