By Kevin Duffy

After a half-century of salmon fishing in the Great Lakes, anglers are on edge.

As numbers of native lake trout and whitefish rebound, numbers of the prized Chinook — or king — salmon have spiraled downward.

“It’s about finding a balance between prey fish and predators in this changing food web,” said Randy Claramunt, a fisheries research biologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

“We don’t want to have a fish community that’s dominated by non-native species,” he said. “But in some cases it can provide a benefit.”

Chinook salmon. Image: Michigan Sea Grant

The rise and fall of salmon in the Great Lakes is a cautionary tale that suggests an ecosystem cannot be restored with single-species thinking. It shows how intricate the interactions are between native and non-native species and how that affects a resource economy.

It’s a tale that began in April of 1966 when first Coho and then Chinook salmon were brought from the Pacific Northwest to the Great Lakes to eat another nonnative fish.

That fish — the alewife — had invaded the Great Lakes through man-made canals.

Its main predator — lake trout — was struggling to survive, and alewives swam in great numbers until their populations crashed. Dead alewives would wash ashore, rotting on Great Lakes beaches. Then they would boom and crash again.

Dead alewives on Lake Michigan shore. Image: Lester Graham, Michigan Radio

Populations got so big that when viewed from above, thousands of the herring-like alewife appeared as a large alien shadow beneath the water’s surface.

“I had heard about an abundance of alewives but was shocked to see one grouping that measured about seven miles (long) by three-quarter miles (wide) in the water,” said Howard Tanner, who led the state’s fish division when the salmon program began 50 years ago.

Tanner, now 92, wanted to control the alewives with Pacific salmon and revitalize Great Lakes sports fishing at the same time.

“To allocate the largest freshwater system in the world for commercial fishing was good but not for conservation,” he said. “What we really needed in the middle of this heartland was an exciting sport fish.”

He got one. Tanner brought the Chinook to the Great Lakes, and by 1970 Pacific salmon were thriving on an ample alewife diet. That, in turn, sparked a thriving charter fishing industry that lured anglers from hundreds of miles away.

Fast-forward 20 years and the scene began to change as other invaders started to filter-feed their way through the Great Lakes.

The voracious zebra and quagga mussels diverted energy and nutrients away from prey fish, like alewife and smelt, by eating the microscopic plants and animals — phytoplankton and zooplankton — they relied on for food.

Howard Tanner planting the first Coho salmon in 1966. Image: Michigan DNR

With their food in decline, alewife numbers began to plummet. That left fewer alewives for the salmon to eat. But resource managers were still pressured to continue heavily stocking the king sport fish that had eaten those alewives when they were abundant.

The remaining alewives can only support so many salmon before each population crashes, Claramunt said.

“We considerably reduced [salmon] stocking in 1998, 2006 and 2013 in an attempt to find the balance between declining prey fish levels and the salmon population in Lake Michigan.”

Claramunt studies this balance using the basic biological principle that predators are limited by what they have to eat.

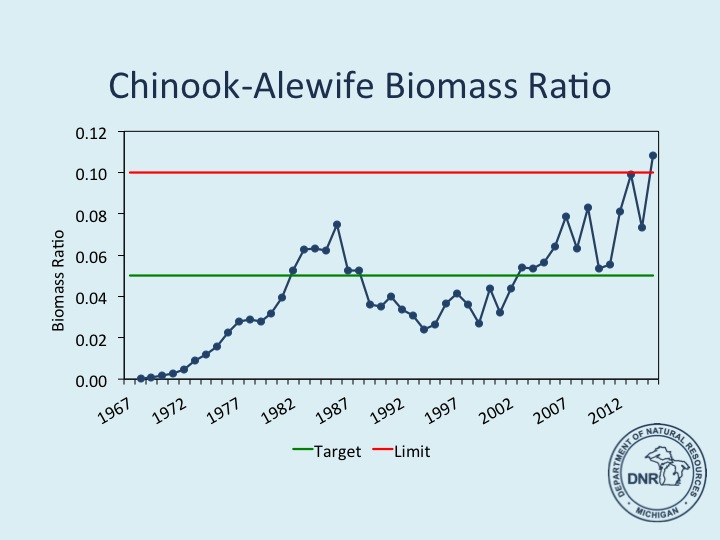

In most ecosystems, one-tenth of the prey’s biomass should be predators to support a healthy predator-prey dynamic, he said.

If there are 10 pounds or less of alewives for every pound of salmon, that’s bad for the salmon because there are not enough alewives to eat.

But if there are 20 pounds of alewives for every pound of salmon, the populations are in balance. The salmon will have plenty to eat, and there will be enough alewives left to reproduce and replenish the salmon’s food supply.

The Chinook-Alewife Biomass Ratio reached its biological limit (0.1) in recent years, meaning there are not enough alewives in Lake Michigan to feed salmon. Management actions like reducing stocking or increasing salmon harvest could reestablish a balanced food web and bring the ratio to a level consistent with lakewide management goals (.05). Image: Randy Claramunt

Lake Michigan has reached that critical point.

“Salmon numbers are coming down but the ratio is staying high because the number of prey are actually declining at a higher rate,” Claramunt said.

Lake Michigan is following a fate similar to southern Lake Huron, where a 2003 alewife collapse forced managers in Michigan and Ontario to terminate stocking programs in 2014.

With fewer catches of fewer salmon, the sport fish legacy is dwindling in Lake Huron, and a salmon rebound is unlikely, according to researchers.

“It doesn’t mean we won’t have Pacific salmon, it just means we have to continue managing and catching them in a way that is sustainable,” Claramunt said.

“People want to see a diverse fishery that includes some Pacific salmon.”

But salmon are not the only Great Lakes fish whose prey are impacted by zebra and quagga mussels.

“Unlike Chinook, predators in the lakes are switching at times or entirely to alternate prey,” Claramunt said.

The round goby — another nonnative invader — has filled the food gap created by invasive mussels.

“Lake trout, Coho, steelhead and brown trout are all doing pretty well on the round goby. The problem is the goby is a benthic species that lives near the bottom, so Chinook rarely feed on it,” Tanner said.

Gobies come from the same region as the mussels, can feed on them and provide a food source that supports native fish in the lakes.

“They provide a critical link that wasn’t there,” Claramunt said.

If nothing else, the story of salmon in the Great Lakes shows how nimble researchers and resource managers must be to keep up with unanticipated consequences in a changing ecosystem.

“The state of the salmon population now and the salmon program over the last 50 years has taught us the lakes are important but changing, and in order to be sustainable, we have to get away from single species thinking,” Claramunt said.

With a Chinook population that’s been reduced by stocking and a food source that’s affected by another nonnative, researchers urge managers to focus their efforts on restoring native species.

But research and monitoring of salmon, alewife and goby will continue as Lake Michigan and Lake Ontario try to outswim Lake Huron’s fate.