Review

By Kevin Duffy

By Kevin Duffy

Some are slimy. Others jump at the sight of humans. But most remain mysterious — cloaked below the water’s surface — and ready to wreak havoc on an unsuspecting ecosystem.

They are the Great Lakes aquatic invaders.

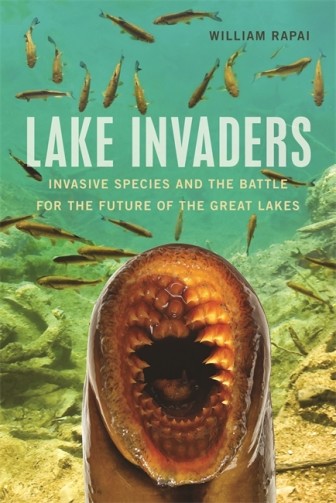

“We have a role in preventing their spread,” said Bill Rapai, author of the new book, “Lake Invaders: Invasive Species and the Battle for the Future of the Great Lakes.”

“We often notice impacts to water clarity and our limited success finding or fishing the species we love, but we rarely think about the direct negative and cascading impacts of invasive species,” he said.

Rapai, an amateur naturalist and avid bird-watcher from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, had no experience with invasive species before writing the book.

“As a bird guy and president of my local Audubon chapter, I’m clued into the world around me. I’m naturally curious. But when it came to invasive species, it was like biology 101,” he said.

Introductory course or not, “Lake Invaders” is deeply researched. It relies heavily on Rapai’s interviews with more than 100 experts, including scientists, activists, politicians, educators and anglers.

And his craft as a former journalist and editor proved useful.

“I wanted to put a face to this Great Lakes issue,” said Rapai, who’s won awards for his work at the Grand Forks Herald, the Detroit Free Press and the Boston Globe.

“I wanted to feature the people who do the research because humans relate to one another better than we do to a spiny water flea or quagga mussel.”

Rapai spent most of his time in the field observing how science was done so he could use storytelling to “amend the mistrust” he saw in large parts of the non-science community.

“The average person does not need the precision of knowledge that a biologist does,” he said. “They need to know how these invasives interact with other aquatic species and with us.

“People need to know they actually have an impact.”

An educational resource and fieldwork narrative, the book provides a window to what’s happening beneath the water’s surface. It uses a candid but dramatic tone to heighten the threat-appeal of each invader it profiles.

From a “fish with a hundred teeth arranged in a terrifying whorl” to a “tiny crustacean with a barbed sword for a tail,” Rapai describes the worst of the worst invaders and the endless mission to control their spread.

The book begins with a familiar anecdote that highlights early industrial prowess — construction of the Erie and Welland canals — and the unintended consequences that result from increased commerce and human migration.

Each of the first seven chapters features a big-impact invader, chronicling its arrival and rise to dominance, control efforts and practical tips to prevent new introductions.

The final chapter reveals behind-the-scenes activism and explains, “Great Lakes states and provinces, and not the federal government, are leading the way on aquatic-invasive-species policy.”

Rapai likens the attempt to stop new introductions to a futile “game of underwater Whac-A-Mole,” but he suggests there is a way for government to appropriately react to new threats.

He recommends that elected officials and managers receive more authority to pool resources across state and national borders and demands that preventative policies be coordinated between states and provinces.

“It is not a story that ends with this book,” Rapai said.

This is an objective but emotional narrative that stretches across each of the Great Lakes.

“Every day there is some new announcement or development concerning Great Lakes invaders, and this book is a snapshot of that.”

“Lake Invaders: Invasive Species and the Battle for the Future of the Great Lakes” will be available April 4 through Wayne State University Press and Amazon ($27.99).

Kevin Duffy is a reporter for Great Lakes Echo