Editor’s note: Landscope is an occasional series about Michigan land use changes documented in the aerial imagery archive at Michigan State University’s Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Systems center.

Southwest Kent County, 1938

A landfill is born

Tiny fields, some trees and a road – that’s how this piece of land the southwest corner of Kent County, Mich., about 13 miles from Grand Rapids, looked like in 1939.

In the 1960 photo below, Route 131 has paved its way through the view finder.

US-131 has shown up in southwest Kent County in this photo from 1960.

In the 60s and 70s the fields grew.

This picture from 1978 doesn’t look too different from the 1960s, but a large landfill is four years away from being constructed.

Then — in 1982 a landfill was born.

In this 1993 image you can see the South Kent Landfill occupying former fields.

The landfill that was built in 1982 is visible just west of US-131.

The South Kent Landfill is one of Michigan’s 48 active landfills for solid consumer waste. In 2013 almost 700,000 cubic yards of ash and trash have been added to the pile. More will come. The landfill won’t be full in at least another 15 years.

The number of landfills for consumer waste have not changed dramatically over the years, but there has been a small decrease. When the Michigan Department for Environmental Quality started tracking them in 1996, there were 56, eight more than today.

The waste from Michigan peaked in 2001 at 48 million cubic yards. The gradual decline after the peak could reflect increased recycling, industry practices to reduce waste generation and reduced construction or manufacturing, said Steve Sliver, spokes

person for the Michigan Department for Environmental Quality.

But although Michigan might have been recycling like crazy, Canada and other states kept dumping their trash on Michigan’s landfills. The total waste disposed in Michigan, including Canada and other US states, did not peak before another five years.

In 2005, 63.9 million cubic yards of consumer waste was shoveled on top of Michigan’s landfills, the biggest number in the state’s history. Then it kept falling every year until it reached 44 million cubic yards in 2012.

Michigan’s economic downturn, leading to a decrease in population and manufacturing of products contributed to the waste decline, Sliver said. So did transportation costs, increased utilization efforts rather than disposal, more accurate reporting of waste types and volumes, and Ontario’s commitment to phase out its exports of municipally-managed solid waste to Michigan.

Although the falling amount of waste was caused mainly by a poor economy, the waste does not have to grow at the same speed as the economy does.

“We are trying to promote more recycling. If we are successful, when the economy recover, it may even [continue to] decrease”, Sliver said.

The Department of Environmental Quality projects a 5 percent decrease in solid waste per year the next five years.

Nationally, the average American throws away their body weight in rubbish every month, according to a Nature article. The U.S. and Japan have roughly the same gross domestic product per capita, but the Japanese are issuing about one third less rubbish per person than the U.S.

Worldwide rubbish is generated faster than any other environmental pollutants, according to the Nature article by Daniel Hoornweg, professor at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology in Oshawa; Perinaz Bhada-Tata, a solid waste consultant in Dubai and Chris Kennedy, a professor with the University of Toronto.

The U.S. and the other 33 countries in the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are still the largest waste generators. In 2012 Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata published a World Bank report called What a Waste. They projected that the waste of the OECD countries will peak by 2050, followed by the Asia-Pacific countries by 2075. But the waste generated by sub-Saharan African cities will continue to grow.

Business as usual will cause solid waste rates to exceed 11 million tonnes per day by 2100, the report predict. That is more than three times today’s rate.

How can today’s waste situation be improved?

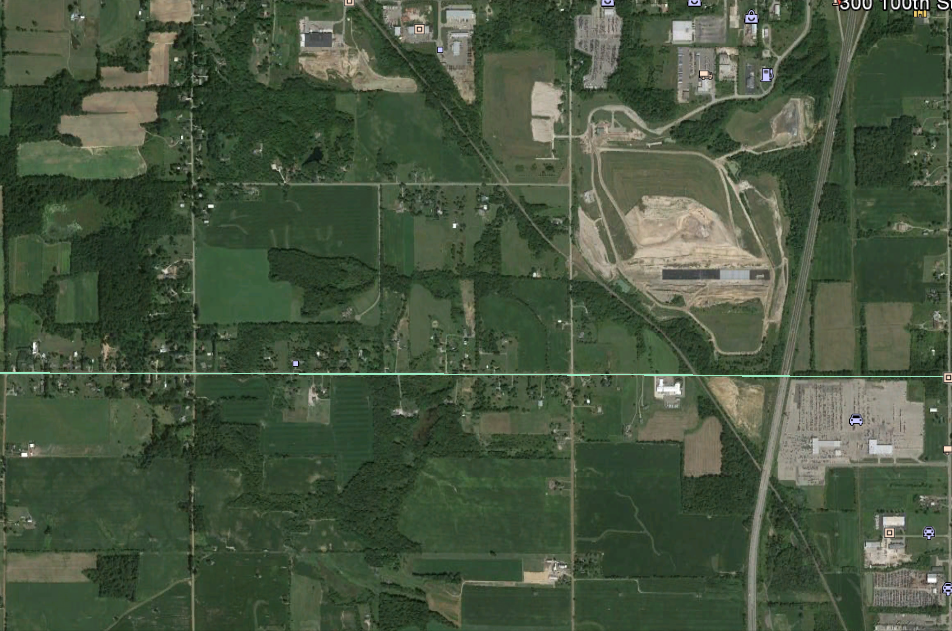

This photo from Google Maps shows the current landscape of southwest Kent County.

San Francisco has a goal of ‘zero waste.’ The city’s goal is that no waste will be sent to landfills by 2020, all will be either reused, recycled or composted.

That’s a goal they share with some of Michigan’s auto mobile plants. The auto mobile makers call it the ‘zero landfill policy’, Sliver said.

One day, South Kent Landfill may become a green field once again.