Editor’s note: Dereth Glance is a commissioner with the U.S. section of the International Joint Commission, a U.S.-Canadian agency that regulates shared water resources and investigates transboundary issues. This is her response to a recent column by Echo Commentator Gary Wilson.

Dereth Glance

Gary Wilson is right. Restoring and protecting the Great Lakes is a Sisyphean task, but one with breathtaking views and opportunities for adventure, nourishment and ultimately, fulfilling work.

Is the quest to address urgent problems in the Great Lakes faltering? The looming threat of Asian carp invasion and the return of harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie headline the litany and legacy of issues that require remediation, restoration and management.

Just as the Greek king Sisyphus spent the afterlife cursed with pushing a boulder up a hill and never being able to reach the top, often the Great Lakes community feels they’re facing a similar uphill battle. Is this fate a punishment or a challenge?

Doing while learning

Perhaps both, but with two steps forward and one step back the Great Lakes have been pushed to ecological limits time and time again. As humans study and learn the causes of stress to the lakes and methods of cleanup, identify opportunities for restoration, and implement techniques to prevent new problems, it is incumbent upon us all to keep doing while learning.

Science has identified the causes of ecological strains on Lake Erie. Propelled by the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, significant successes have been achieved to improve Great Lakes health by reducing persistent toxic loading, excessive nutrient pollution, and establishing focused work to remediate Areas of Concern. But change is the nature of the world, and we need to recognize and adapt to a changing world.

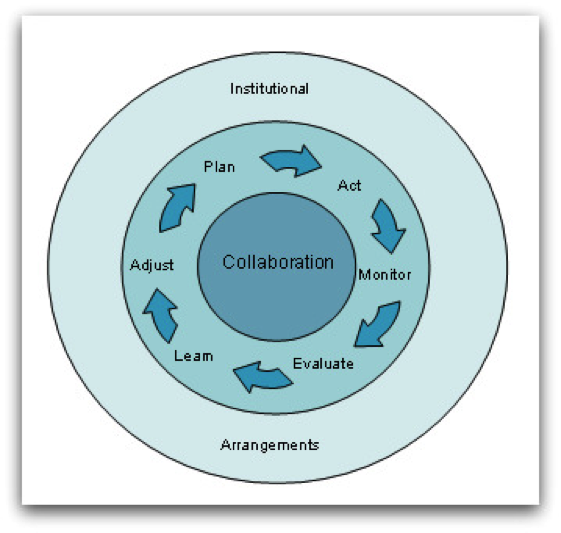

The adaptive management cycle highlights the importance of collaboration and institutional arrangements.

Action is the second step of the six-step adaptive management process: Plan, Act, Monitor, Evaluate, Adjust, and begin again.

Wilson’s criticism of the “study and repeat” cycle is dead on. Without acting, evaluating, and learning, the process chases its tail instead of reaching the solution. The International Joint Commission (IJC) has endorsed the six-step approach for the Great Lakes, because without action based on learning, the boulder slips back down the hill.

Institutional arrangements nest around this cycle to promote collaboration and measure performance objectives.

To this end, the IJC expects to release its Great Lakes adaptive management strategy next year.

Familiar problems, new challenges

Perhaps déjà vu is unavoidable in the Great Lakes. Thick mats of decaying algae stink up the shores of Lake Erie, while massive algal blooms thicken the water to a pea soup consistency that’s devoid of oxygen and harmful to aquatic life. Previous investments thwarted the blooms by reducing excessive nutrients from sewage treatment plants in 1970s. Now, warming waters, more intense rain events, and abundant phosphorus fertilizer are running off from farm fields to feed the “Lake Erie Algae Monster.”

The IJC’s Lake Erie Ecosystem Priority (LEEP) draft report summarizes the current state of science, highlights the actions we can take now, and recognizes that continual monitoring and performance evaluation must inform action plans. We would be foolish not to take action, to ignore results, and fail to adjust accordingly. Nowhere is this more urgent than Lake Erie.

Wilson’s praise for the IJC’s LEEP draft report is appreciated. It is important to make general observations in response to Wilson’s assessment.

Laws, standards, voluntary efforts

First, we do know enough to act on critical threats to the Great Lakes. Incomplete understanding of Asian carp or harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie does not absolve us, the members of the Great Lakes community, of the responsibility to act. Reducing the nutrients that contribute to such blooms is an imperative. Voluntary efforts have a place, but when they fall short, we must not shy away from laws and standards that bring us closer to the goal. After all, at the dawn of the modern environmental age in the 1960s, new laws played a major role in reducing pollution.

Can a Sisyphean effort move the Great Lakes restoration boulder?

Second, we do need to keep learning. Sometimes research and study unfairly get a bad name. The Great Lakes are an incredibly complicated system, made more so by the monumental changes being effected by climate change, urbanization, and invasive species. To the extent that new research brings us measurably closer to grasping an aspect of the Great Lakes, further research and study is essential. We must be willing to acknowledge our information gaps and the means to address them.

Of course, study alone is insufficient. We’ll never know everything about the dynamic Great Lakes, but we’ll know enough to act intelligently and effectively. Study and action are not mutually exclusive. In our Great Lakes community, we have the capacity for both.

Hard work worth doing

As U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt once commented, “Far and away the best prize that life has to offer is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.” And after all Albert Camus concluded for Sisyphus, “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart.”

The enduring work of Great Lakes stewardship for current and future generations is fraught with frustrations and backslides, but it is work worth doing well. With a combination of learning and action, embodied in adaptive management, we can get that Sisyphean boulder further up, if not to the top of the hill.

The Great Lakes will be better for it.