By Gray Longcore

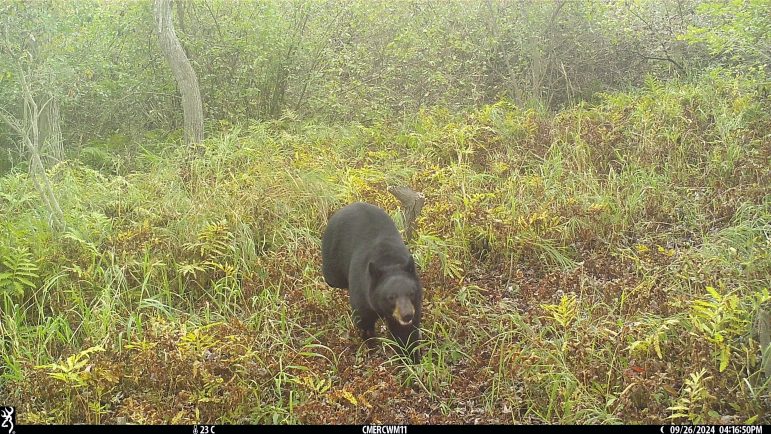

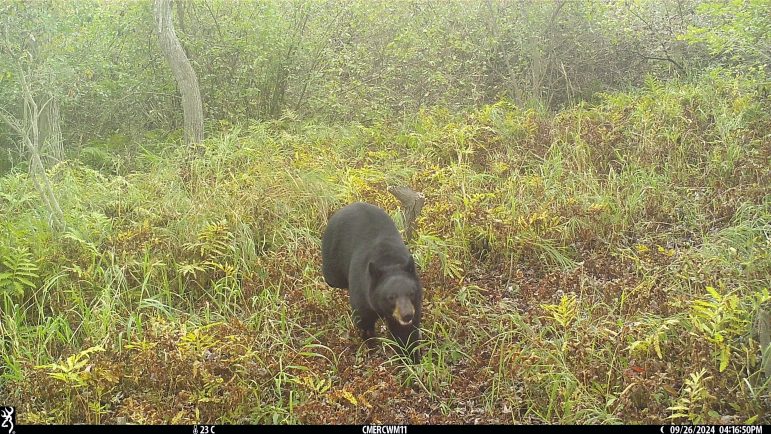

“There’s bears here?” That was a common response this spring to the first public display of photos of a black bear taken from trail cameras just a half-hour drive from downtown Lansing. These sightings are part of a recent southward push of black bears in Michigan.

By Joshua Kim

Water quality experts are using DNA tools to track down contamination responsible for beach closures and reduced recreational opportunities along the Great Lakes and other Michigan inland lakes and streams.

By Victoria Witke Catch and release ethics is credited for the fact that smallmouth bass in Lake St. Clair have been getting larger over the past 50 years, a DNR study finds. Other factors may include warming Great Lakes water temperatures and longer growing seasons due to climate change.

By Kayte Marshall

It only takes a sunny afternoon, a yard full of dead leaves and one bad decision to turn spring cleaning into a wildfire. The DNR and National Fire Protection Association are advising homeowners to fight fire with foresight this year, especially in Northern Michigan where winter storms left massive amounts of flammable debris and dead trees on the ground.

More Headlines