Display cases sit empty in The Fish Monger’s Wife fresh fish store in Muskegon. Drive up sales, with proper social distancing, continue outside. Images: Amber Petersen

By Kurt Williams

Michigan’s commercial fishing is critical infrastructure during the pandemic, yet some of its practitioners may not survive COVID-19.

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer designated commercial fishing as critical to the state’s food supply on April 9, allowing the industry to continue to fish. Yet there’s concern whether fishers will be able to sell the fish they catch.

The state followed federal guidelines issued by the Department of Homeland Security to make the designation, said James Dexter, the state’s fisheries chief.

“Our 13 fishers bring to dock about 5 million pounds of fish (per year), which provides a significant number of meals,” Dexter said.

He’s unsurprised the industry is considered critical.

“Fish (are) an extremely valuable source of protein for people., It’s an extremely good product. It’s all wild caught fish – a Pure Michigan product. People want a varied diet and fish is important,” he said.

In the time of coronavirus, this is a good news-bad news story for commercial fishing. They can fish, but they’re concerned about finding a market for the fish they catch.

Commercial fishers are glad to get out on the water and set their nets, but they’re not sure where they’ll sell the fish they catch, said Amber Petersen.

Petersen is married to a third-generation commercial fisher out of Muskegon whose family has been plying the Great Lakes since 1927. She and her husband also operate a fish processing business and fresh fish market.

In normal years, much of their catch is destined for restaurants along the Lake Michigan coast and in tourist towns in Northern Michigan.

Commercial fishing is tied to the restaurants, Petersen said. Now, with most restaurants in the state closed and the summer tourist season just around the corner, Petersen worries what may happen to the industry and her own family.

“This could be the kind of thing that wipes out people,” she said. COVID-19 hit in early spring, just as the season started. If it lasts until summer, fishers will be in serious trouble.

The state may consider fish to be an important part of a varied diet, but variety isn’t what state-licensed commercial fishers bring in from the lakes. Their license allows them to keep a single species: lake whitefish, said Petersen. If they catch other commercially valuable species like walleye and lake trout in their nets, they have to throw them back into the lake.

Being restricted to fishing only for whitefish keeps Michigan fish out of large grocery chains, Petersen said.

She and other fishers would like to get access to grocery chains to sell their whitefish, especially now with the restaurants closed because of COVID-19, but large grocers like Meijer and Kroger won’t buy from Michigan fishers because they can offer only whitefish, she said.

Meijer and Kroger want to buy whitefish, but they also want walleye and lake trout, Petersen said. Since U.S. grocers can’t get those other species from Michigan fishers, they turn to Canadian Great Lakes commercial fishers. The Canadians can fish for walleye and lake trout, in addition to whitefish, so they’ve cornered the market for Great Lakes fish in the major grocery chains, she said.

“Canada has a monopoly on everything,” said Dana Serafin, who fishes commercially in Saginaw Bay and Lake Huron. He’s exasperated when he thinks about what’s happening to commercial fishing in Michigan, especially during the pandemic.

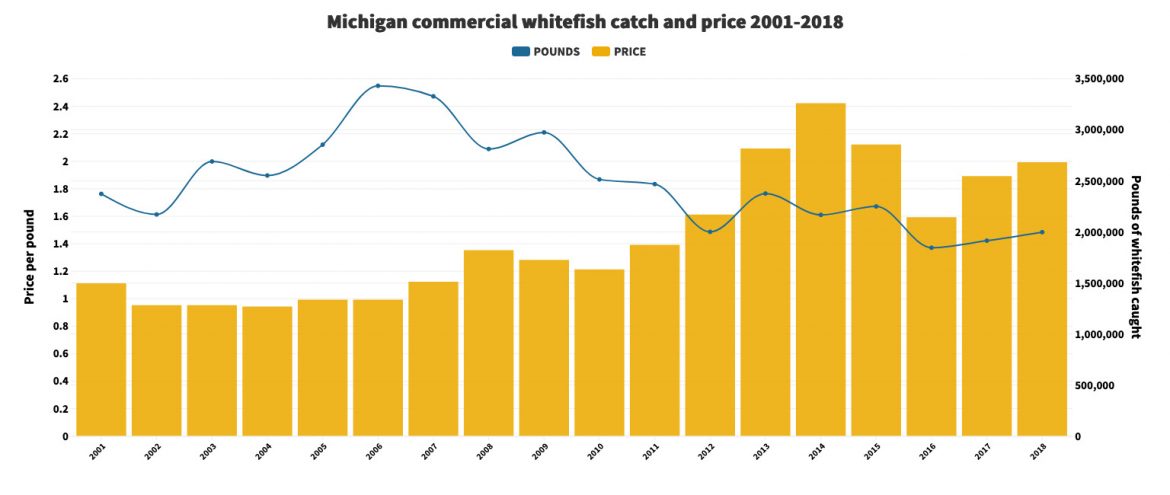

Pounds of whitefish caught and price per pound for the fish in Michigan 2001-2018. Michigan Department of Natural Resources data.

From 80% to 90% of the whitefish he catches stays in Michigan, going to restaurants up north and on the west side of the state, Serafin said. Now with the restaurants closed he’d like to sell fish to grocery stores.

He can’t contract with Meijer or Kroger because they want more than just whitefish to sell to the public, he said.

Serafin becomes increasingly frustrated as he talks about the state’s position on commercial fishing in Michigan.

Michigan plants walleye and lake trout by the millions but commercial fishers aren’t allowed to keep them when they catch them, he said.

That’s because the sport fishing industry doesn’t want those species being caught commercially, Serafin said.

“The sport groups allowed the Canadians to have a monopoly,” he said.

But for Serafin, those fish could mean added income to the dwindling numbers of the state’s commercial fishers and processors.

It would be especially vital while the restaurants are closed statewide, he said.

It’s not like the fish planted by the state are going to stay in Michigan’s waters, Serafin said. “They’ve got tails, they tend to move.”

“I know all them guys in Canada and they laugh how stupid we are,” Serafin said.

“We started out planting walleyes. Who takes the walleyes? Canada. Who sells them back to us? Canada. Canada doesn’t plant walleyes. They think it’s hilarious we’re that stupid to plant them, they catch them and sell them back to us,” he said.

They even label their fish “Pure Michigan, processed in Canada,” Serafin said.

Michigan fishers are convinced that walleye and lake trout are abundant and wouldn’t be negatively impacted by commercial fishing.

Advocates of recreational fishing in Michigan disagree.

“I would tell you as both a sport fishing enthusiast and fisheries biologist, those popular species are fully allocated,” said Bryan Burroughs, the executive director of Trout Unlimited in Michigan.

Lake trout and walleye numbers are carefully monitored and regulated in the Great Lakes by the state and federal governments, he said. While walleye are doing comparatively well in Michigan waters, especially in Saginaw Bay, lake trout still are unable to sustain their populations through natural reproduction.

Nobody other than commercial fishers thinks there’s an overabundance of lake trout in the Great Lakes, Burroughs said.

He doesn’t want to see lake trout added to the species being caught by Michigan’s state-licensed commercial fishing operations, and says the state is managing the species well.

The different approach to managing fisheries between Canada and Michigan comes down to economics, he said. “Michigan is making a much more intelligent use of its fisheries.

“The state ranks in the top three of all states in the country for sport fishing, whether you’re talking about dollars spent or numbers of out of state people visiting the state to fish,” he said. All these people fishing inject far more money into the local economy than commercial fishing.

“On average, people fishing on the Great Lakes spend about $225 per day on fishing trip expenditures,” Burroughs said. Recreational anglers can turn 100,000 pounds of walleye into $300,000 of local expenditures.

If Michigan fishers want to diversify their catch to improve their economic situation, they should develop markets for species not currently being caught recreationally or commercially, like drum and burbot, he said.

Eventually the pandemic will end, and the economy will open back up. When it does, what will that mean for the state’s commercial fishing industry? Will the current 13 state-licensed operations still be in business?

Petersen worries about rural operations without a large enough local population to buy their fish while the restaurants are closed. Some of them may not make it if this lasts into the summer, she said.

It’s ironic that they’ve been designated as critical infrastructure by the state, Petersen said.

Before the shutdown, Michigan was considering legislation to raise fees on commercial fishing operations and designate walleye and lake trout as sport fish, she said. That would slam the door on commercial fishers’ hopes of expanding their catch beyond whitefish.

“We’re not loved by the state of Michigan,” she said.

She was scheduled to testify at a Senate hearing about the legislation before the pandemic struck. Now she wonders what will happen after COVID-19.

“We are small family organizations. It’s like picking on the two-person dairy farm when you come at commercial fishing in Michigan,” Petersen said.

Dexter, the state’s fisheries chief, said he understands the industry’s challenges.

But the Whitmer administration supports the bills as they are written, he said.

He foresees Michigan’s commercial fishing shrinking more to an even smaller number of larger operations.

He compares it to American farming which used to have 1,000 farmers farm 1,000 acres, he said. Now 100 farmers farm 10,000 acres.

Commercial fishing faces a similar evolution, he said, where fewer licenses, but larger operations will continue to provide the fish people want

Dexter acknowledges that COVID-19 may cause some to rethink commercial fishing’s place in Michigan’s economy and food supply.

“I would imagine that the conversation potentially might change once the world gets back to some semblance of normalcy and there (are) more hearings on these bills, because things do look different now,” Dexter said.

“That will be up to the industry to make those arguments.”