By Georgia Hill

Many local governments in Michigan are pursuing plans to adapt to climate change, but few address issues faced by communities disproportionately affected by the climate crisis, according to a recent Michigan State University study.

Households across the country face increasing climate-related threats, including winter storms knocking out power, wildfires destroying property and pollution tainting drinking water.

But low-income communities and other marginalized populations often suffer more frequent and severe environmental hazards while having fewer resources to recover from climate-related disasters, said Graham Diedrich, an environment and public policy researcher who authored the study.

While governments around Michigan such as Detroit, Grand Rapids, and Traverse City work to address the escalating climate crisis, many overlook the needs of the groups most vulnerable to these impacts, said Diedrich, who conducted the research as part of his independent research graduate work.

“It’s crucial that all community perspectives are involved in making these plans,” Diedrich said. “That involves outreaching engagement efforts, and further studying the ways these plans impact marginalized people.”

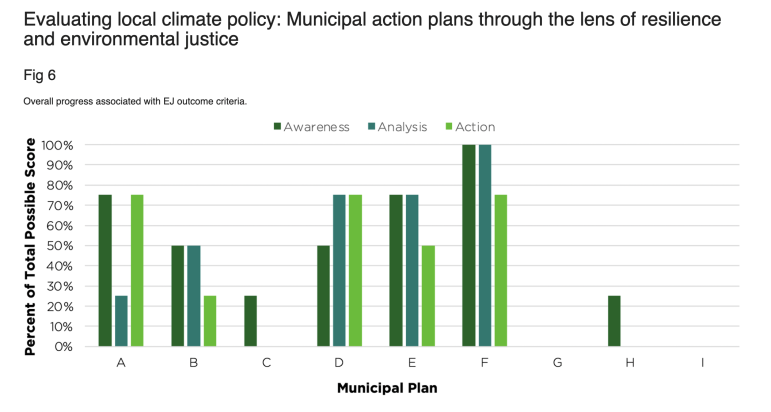

The study, published in the journal PLOS Climate, assessed nine local climate action plans in Michigan based on resilience and environmental justice across three categories: awareness, analysis, and action.

It found that many plans acknowledged the urgency of the climate crisis and addressed topics normally considered to be relevant to climate resilience work, such as transportation and greenhouse gas emissions.

But only a few of the plans addressed specific issues, such as air pollution or water infrastructure, which low-income communities are more likely to be affected by. Even fewer addressed the needs of marginalized communities on a local level. Concrete, actionable solutions were also rare.

While many local governments want to address environmental justice issues, much of it comes down to resources and capacity. Limited funding and staffing often cause these issues to go overlooked, Diedrich said.

That is what climate groups such as the Michigan Climate Action Network are working to solve. Denise Keele, the executive director of MiCAN, works to incorporate voices of local underprivileged communities into larger municipal climate plans.

“There is no solving the climate crisis unless we actually address racial inequality and economic inequality,” Keele said. “Otherwise, all the solutions that are presented to us will just lead to more inequity and continue to exacerbate the justice crisis, which is the root of the climate crisis.”

MiCAN works with city planners and stakeholders to help write plans and carry community voices to local governments that make climate decisions.

Many plans contain great technical and infrastructure solutions, but don’t offer solutions for people who are facing severe flooding or live in homes that aren’t insulated against extreme winter weather, Keele said.

One way to build environmental justice into these plans is education, said Elise DeCamp, MiCAN education advisor. Her work promotes climate change education across the curriculum and sustainability initiatives that provide resources for teachers and students.

It’s also important for government officials to listen to their community when it demands action, DeCamp said.

“Hearing the voices of impacted communities and educating people on what’s happening in different areas needs to be part of the discussion in these action plans,” DeCamp said. “What these people are struggling with, and how we can help.”