By Ruth Thornton

A recent study has found dozens of previously unknown “forever chemicals” in the fish, mussels and waters of Lake Huron, revealing more contamination than previously realized.

Researchers from Clarkson University in New York looked for new contaminants, said Bernard Crimmins, an environmental analytical chemist with the university and a co-author of the study.

“There are thousands of PFAS chemicals in use and potentially out in the environment. We need to expand our understanding,” he said, “to see what the true contamination is in the environment.”

The group of chemicals known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, includes around 15,000 chemicals. They are persistent in the environment and commonly referred to as “forever chemicals.”

Most are not well-studied, and some are known to be associated with significant human health problems, including kidney and prostate cancers, decreased ability to fight infections, decreased fertility, higher cholesterol levels and increased risk of obesity, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The chemicals are all human-made and have been produced since the 1940s for use in many consumer products, some labeled as water- or stain-resistant.

Now researchers are scrambling to understand the health and environmental effects of these chemicals.

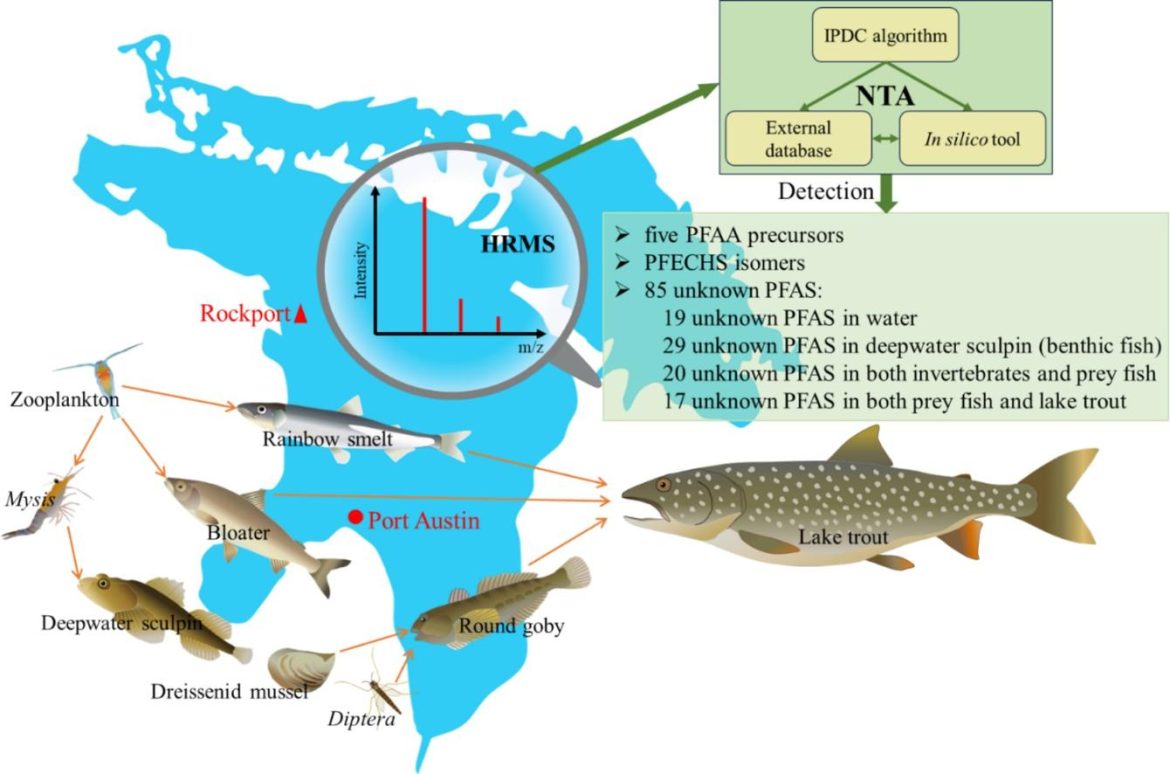

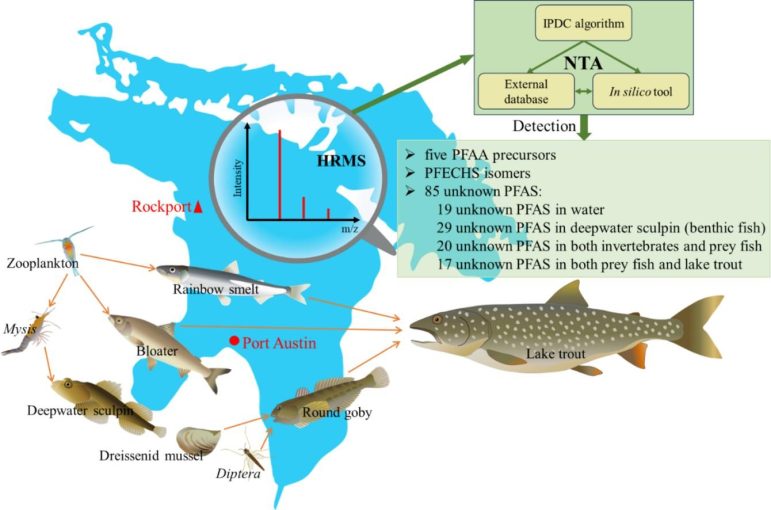

Crimmins said the study was novel in that it looked not only at the known PFAS chemicals that most other labs study. It also employed what is called a “non-targeted analysis” to find previously unknown contaminants.

“Every year, we go out and sample all of the different compartments of the food web” in one of the Great Lakes, Crimmins said. Last year the team sampled sites near Rockport and Port Austin in Michigan.

The study appeared in the Journal of Great Lakes Research.

Crimmins said chemicals that accumulate in the flesh and fatty tissues of fish, especially top predators and popular trophy species such as lake trout, likely have adverse health impacts on people who eat them.

“If they’re accumulating up the food web, that means that they’re enriching in the body,” he said, referring to the accumulation of the chemicals in the fish.

“They’re not doing anything good to those species,” Crimmins said.

The scientists then focused on those chemicals for further research since they’re the most likely to be ecologically relevant.

Other chemicals of concern include mercury, dioxin and PCBs, according to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Service’s Eat Safe Fish Guides.

“Captain Steve” Hubert runs Chum Bucket Charters, a fishing charter service out of Alpena. He said he’s concerned about contaminants such as PFAS hurting his business.

He said while he is fortunate to keep busy, he’s heard concerns from clients about contaminants in the fish they catch.

“I tell them to not keep those larger fish because they’re just nothing but a filter,” he said. “As they eat, contaminants build up like a filter would, and the older that fish is, the more PFAS and these other chemicals get into his body.”

“We’ll take the photos of the larger fish, release the bigger ones and then keep the smaller ones for eating,” Hubert said.

PFAS manufacturers aren’t required to prove their products are safe before using them in a wide variety of consumer items, including food packaging, non-stick cookware, clothing and carpets.

Gillian Miller is a senior scientist with the Ecology Center in Ann Arbor who was not involved with the Clarkson University study. She said such research is important despite being time-consuming and challenging.

“There are so many different PFAS,” Miller said, “it’s difficult to get a handle on what all is in the environment.”

Miller said the Ecology Center and other environmental advocates have been pushing for government regulation of PFAS as a class rather than individual PFAS chemicals.

“The one-by-one regulation approach is ineffective,” she said. “It’s a start, but it will take forever to regulate this class of compounds in a way that’s protective of human health and, certainly, of ecosystem health and wildlife as well.”

Miller said the current state and federal regulatory structure allows manufacturers to produce and release chemicals without testing first to safeguard human health.

“The system is set up to allow new chemicals to be used with limited information and without putting a burden on producers to demonstrate safety beforehand,” she said.

Many consumer products contain PFAS and federal regulations do not limit most of their uses.

Michigan is one of the few states limiting PFAS chemicals in drinking water. But of the thousands of PFAS chemicals Michigan regulates only seven.

No regulations exist to limit the use of most of the rest, and there is little information on potential health or environmental impacts.

Last year, Rep. Penelope Tsernoglou, D-East Lansing, introduced a bill to limit PFAS chemicals in consumer products.

“The more I learned about how they’re in so many of our products, and how they can lead to so many health impacts, including cancer,” Tsernoglou said, “that’s something that I want to avoid, not only for my family, but for everyone’s family.”

Tsernoglou said substitute products are available that companies could use without PFAS.

“Most people don’t know that PFAS are an issue and something they’re exposing themselves and their families to on a daily basis,” Tsernoglou said. “We shouldn’t be exposing ourselves to these chemicals if there are other alternatives.”

Her bill, however, was not passed last year. It would need to be re-introduced this year and it is uncertain if it would get the needed support this session, Tsernoglou said.

Hubert, the charter boat captain, says he advises clients to trim the fat off the fish to remove some of the contaminants and get the fish as healthy as possible.

“I still believe it’s probably better to eat one of those than a farm-raised fish that’s been in a display case from a market,” he said. “Who knows what kind of chemicals they give those fish.”