By Ayushya Gautam

Big buildings, concrete and roads paint Detroit, just as they do other cities across the country. As a result, the city’s temperature also tends to be hotter than in nearby communities.

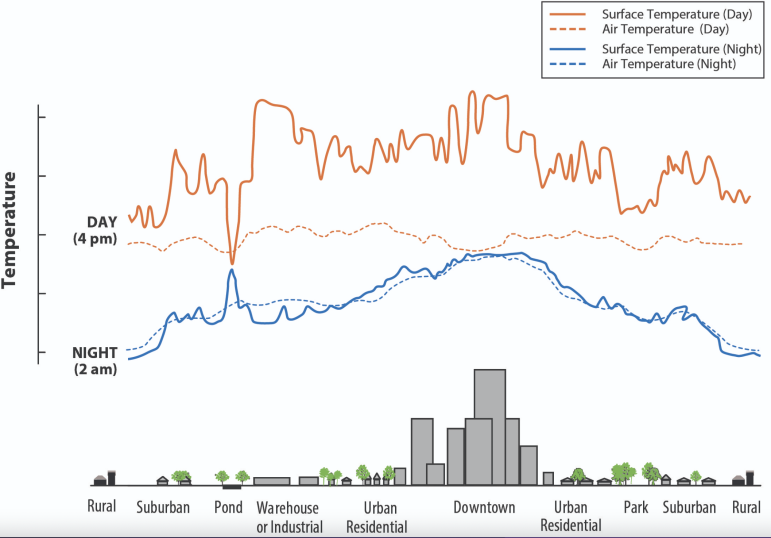

Cities are prone to the heat island effect, a phenomenon in which urban areas experience more heat than rural or even nearby suburban areas due to the concentration of infrastructure.

And although summer is still six months away, experts say there’s ample reason to worry about the problem because of how cities are built.

“Impervious surfaces like pavement or asphalt absorb the sun’s energy and then re-radiate it out as heat, sometimes even hours later,” said Robert McDonald, the lead scientist for nature-based solutions at The Nature Conservancy. “That can mean 5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit differences between the urban environment and the rural environment.”

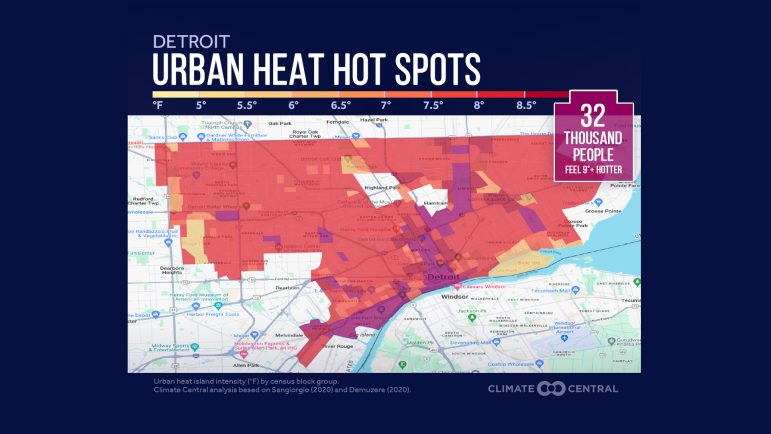

On average, Detroit’s urban areas are at least 8 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than nearby rural locations.

Within the city, certain neighborhoods experience even greater temperature disparities. Around 3,160 residents live in intra-urban heat islands where temperatures are at least 10 degrees hotter than other nearby areas.

A similar dynamic plays out in other cities around the Great Lakes region, including Chicago, Cleveland and Milwaukee.

For the most part, these intra-urban heat islands disproportionately affect communities of color and lower-income communities, studies show. This inequality is structural, McDonald said.

“An inequality in heat risk”

In most U.S. cities, wealthier households left urban centers and moved toward the suburbs, particularly during the “white flight” period in the 1950s and 1960s, McDonald said.

The wealthier, predominantly white, suburban households now have significantly more tree cover.

“Our neighbors in the suburbs have on average about 30% more tree cover canopy than we do here in the city,” said Lionel Bradford, the president and executive director of Greening of Detroit. “So, you look at some of the more affluent neighborhoods –– their tree cover canopy is a lot greater than that of the poorer neighborhoods.”

According to McDonald, areas with more tree cover can be considerably cooler than areas that do not.

“Surface temperatures can change a lot when you have that shade. So, you’ll hear stories of, ‘It’s like, oh, 15 Fahrenheit cooler on the pavement under the shade than not,’” McDonald said. “Differences in air temperatures for a row of street trees are more modest –– 2 to 4 Fahrenheit is pretty typical.”

The disparity in tree cover, therefore, means that neighborhoods that are predominantly populated by minorities and lower-income households are more likely to be exposed to hotter temperatures than predominantly white or wealthier neighborhoods.

“That’s kind of the current state of affairs, that inequality in income and this history have led to an inequality in heat risk,” McDonald said. “There’s also, related to that, big differences in vulnerability.”

“You were living dangerously”

The communities most disproportionately affected by intra-urban heat islands are also more likely to already be experiencing broader environmental injustices, experts say.

Sandra Turner-Handy, the interim president of Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, remembers growing up in the Motor City in the 1960s.

Because not everyone had cars at that time, many Detroiters tended to live close to where they worked to have an easier commute, she said. However, people did not realize the health impact that living so close to major industries would have.

“Work was very close to where people lived, not knowing that if you lived near Ford Foundry or U.S. Steel and other entities like that, you were living dangerously,” Turner-Handy said.

“You were living in areas where our air quality was out of attainment or our water quality was impacted or our soil was impacted. We didn’t realize the high rate of cancer in our city or the high rate of respiratory illnesses was coming from the very environments that we lived in,” she said.

White flight into the suburbs was simultaneously compounded by discriminatory housing practices, such as redlining, which resulted in minority and lower-income communities being concentrated into certain neighborhoods –– areas similar to the ones Turner-Handy recalled from her childhood.

In addition, these communities also became prime targets for cities and companies to build hazardous facilities, which brought further adverse health impacts.

“If you’re a city and you’re trying to locate a new facility that’s going to burn trash or you are a company trying to locate a facility that’s going to have really low wages for your workers, you’re drawn to low-income communities,” McDonald said.

And so, you’re drawn to these neighborhoods that already have a high environmental burden, and the burdens tend to stack up over time in a way that’s really unfair,” McDonald said.

Turner-Handy saw that come true in Detroit when the city built a waste incinerator in 1989.

The incinerator exacerbated respiratory illnesses for residents, including Turner-Handy herself, who suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The incinerator closed in 2019 after years of campaigning by Turner-Handy and other advocates, and it was demolished last year.

“They didn’t think to put [the incinerator] in Bloomfield Hills or Farmington Hills, which are some of the major suburban areas, or Grosse Pointe,” she said.

Urban and intra-urban heat islands exacerbate already-existing health issues.

“The number one health impact of these [heat] stress-related illnesses is going to be respiratory illness,” Turner-Handy said.

“When the heat gets so oppressive, you are going to start experiencing these health impacts with not being able to breathe. You literally have to go to the hospital because you can’t breathe,” she said.

Heat islands can also increase the likelihood of heat-related deaths and other illnesses such as heat stroke, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. This is exacerbated further during heat waves, which are becoming more common than before.

That trend highlights the importance of cooling, both individually and on a community level, experts say. However, socioeconomic disparities can persist when it comes to cooling, too.

“Low-income households have less air conditioning on average,” McDonald said. “Less access to air conditioning and they tend to run it less even when they have it because of concerns about [higher electricity bills] and they’re more likely to have preexisting health conditions.”

“So, the people who get in trouble during heat waves are people with cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases like asthma, etc. All of those things stack up and mean that heat waves are more dangerous in lower-income neighborhoods.”

“Paris of the Midwest”

Greening of Detroit was founded the same year the waste incinerator was built in the city. The nonprofit focuses on community forestry and related initiatives, educational programs and community engagement efforts, Bradford said.

“Detroit was once known as the ‘Paris of the Midwest’ because of its tree canopy cover,” he said. “They would often say that if you flew over Detroit, you couldn’t see the streets because of the tree canopy cover.”

“But between 1950 and 1980, we lost maybe half a million trees in the city,” he said.

Greening of Detroit plans to plant 75,000 trees over the next five years, Bradford said, especially in communities that don’t currently have many trees. He finds this to be the most effective way of minimizing the heat island effect.

The equitable distribution of tree cover is also particularly important as climate change makes heat waves more intense and frequent, McDonald said.

“If we put more trees in neighborhoods that already have a lot of them, we’re wasting some effort,” he said. “Whereas if you concentrate that effort in the neighborhoods that are most at risk from heat, you’re getting more benefit for the dollar you spend.”

Green spaces are crucial in combating extreme heat and the heat island effect, whether through increased tree cover and vegetation, or green roofs. The EPA lists both among the main strategies for cooling heat islands.

“We want our youth to come out and enjoy nature. We want the elderly to be out in nature,” Bradford said. “We know how important it is for us to breathe fresh air and not have all the health problems that we tend to see here in the city of Detroit.”