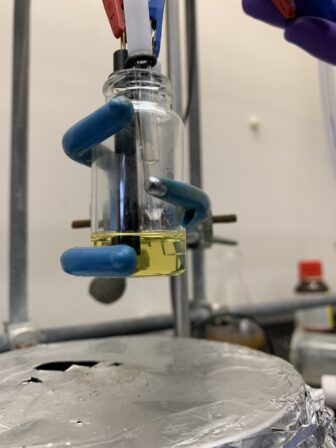

A catalyst mixture is examined by three electrodes. This solution will be used during the CO2 conversion process. Image: Marcus Drover

By Jack Armstrong

University of Windsor researchers are laying the groundwork for what they hope someday could produce fuel from a car’s exhaust.

Marcus Drover, a chemistry professor at the University of Windsor, is the head of a research team investigating how to convert carbon dioxide exhaust produced by the burning of fossil fuels into fuel. The research could one day lead to technology that captures car exhaust or industrial pollution and converts it into energy. Carbon dioxide is the most abundant greenhouse gas released by human activities, and finding a way to recycle it could help fight climate change.

There’s still a long way to go. For now, an application this direct remains a pipe dream, Drover said.

His research involves building a scaffold of elements around a metal center. Researchers look for elements that will react with the metal and serve as a catalyst to break the chemical bonds of carbon dioxide.

Once these bonds are broken, elements can be introduced to create new molecules, said Marissa Clapson, a University of Windsor postdoctoral researcher. For example, introducing hydrogen could create methanol, which can be used as an alternative fuel.

Burning methanol still produces carbon dioxide but much less than the burning of traditional fuels such as gasoline, according to the EPA.

“The thought process there is that we can take these really abundant metals, and take something like carbon dioxide which is harmful to the environment, and turn it into something that we can actually use like a liquid fuel,” Clapson said.

The group partnered with Canadian oil company Imperial Oil Limited after Drover proposed these catalysts as precursors to carbon conversion.

One type of technology their research could lead to is something like an air filter for carbon dioxide, said Joseph Zurakowski, another University of Windsor researcher.

“What we’re hoping to design is a system of nickel that’s sort of embedded in some sort of polymer, like a plastic,” Zurakowski said. “Essentially the nickel atoms are going to be reactive towards CO2, and in a perfect world you would just have it out in the air, and it would take CO2 out of the atmosphere.”

The filter could come in the form of a mesh or a net placed over a car’s exhaust pipe, Zurakowski said. The captured molecules could then be harvested and converted into fuel.

Researchers are far from implementing this solution in the real world. The first step is to determine if a metal can “grab” CO2, before bonds are broken and reagents are added to convert the molecules, Clapson said.

“Where we’re at is exploring the, ‘how do we even do it?’ phase,” she said. “We’re exploring how carbon dioxide even interacts with these metals.”

This experimentation is done in a glove box, where lab workers like graduate student Dante Conflitti mix chemicals.

“I throw my hands in there, and we have a bunch of chemicals…I’ll mix different amounts,” he said.

Zurakowski said the microscopic size of molecules makes it hard for a researcher to know what they’ve actually created.

“It’s like doing Lego, but you can’t see any of the Lego,” he said. “So you have to use tools at your disposal to go and figure out the color, like ’Is it yellow blocks or red blocks?’ and then, ‘How are they connected?’”

While the successful application of the group’s research likely wouldn’t offset all the sources of human-created carbon dioxide, it could create a more circular system for emissions, Drover said. Governments around the world are faced with the increasingly urgent need to pivot away from fossil fuels.

“I would be reluctant to suggest that we are going to get away from carbon-based fuels in the decades to come,” Drover said. “[The research] does provide an opportunity wherein we can begin to think and translate the learnings here into forward pushes.”