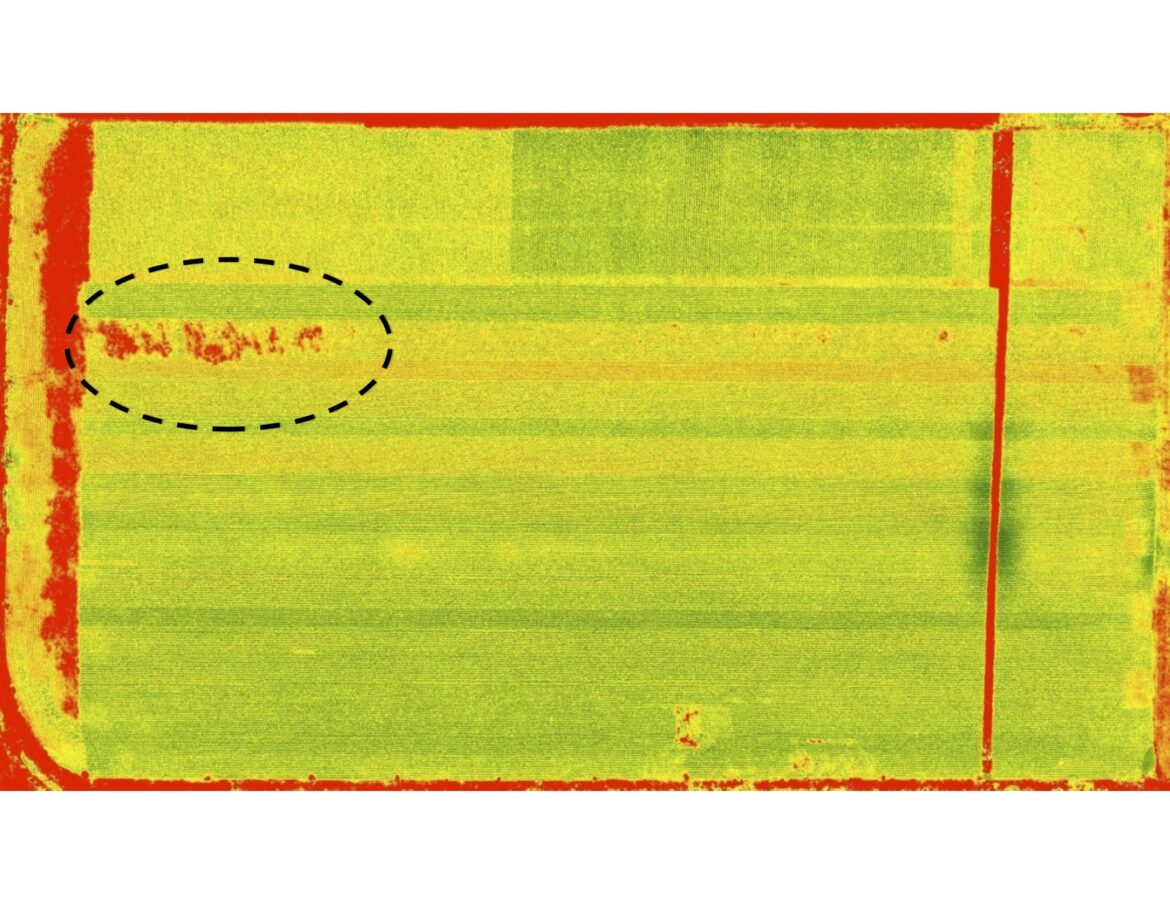

This scan shows a cornfield as seen from a drone. Green and yellow indicate healthy plants and red indicates bare soil, dead plants or, in this case, an insect infestation. Image: MSU RS&GIS

By Nicholas Simon

Capital News Service

In the sky above one of the largest Christmas tree farms in North America, visitors are more likely to hear the whirring blades of a drone helicopter than the jingle of Santa’s sleigh.

“We fly over a field and, using drones, we collect imagery and create 3-D models that help us determine how tall the trees are and help determine a count of those trees,” said Kate Dodde, a drone pilot for the Dutchman Tree Farms in Manton in Northwest Michigan, south of Traverse City.

Other Michigan farmers across the state say that the use of drones could revolutionize farming, but researchers working with drones say federal laws fail to meet their needs.

“You have to be in sight of the aircraft with unaided vision and you can’t use binoculars.” said Robert Goodwin, project manager for Michigan State University’s RS&GIS, which stands for Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System. “You can use extra people in the field with radio contact to keep an eye on it. But, if your using drones you’re trying to limit labor, not bring more people into the field.”

Farm advocates say that regulations confuse farmers who would otherwise adopt the technology.

“I think a lot of farmers are still trying to figure out what they all need to do for regulations,” said Theresa Sisung, the industry relations specialist for the Michigan Farm Bureau. “It depends on what they want to do with their drone.”

Custom software allows the drone to identify the quantity and height of Christmas trees in a certain plot. Inventory like this used to require a team of people taking measurements for each tree by hand. Image: MSU RS&GIS

The Federal Aviation Administration determines which regulations and permits apply to drones based on how high they fly, how much they can lift and whether they are for commercial or private use, Sisung said.

Farmers have found temporary workarounds to restrictions, such as the need to keep the craft in sight.

“We bought a bigger drone; we went from a (12-inch) drone to a 3-foot-wide drone that’s bright orange,” Dodde said. “With that, we can fly further and farther because we can see it.”

The FAA uses the Advanced Aviation Advisory Committee to regulate commercial drones. Until recently none of its members represented farmers.

In January, Congress passed a bill introduced by Sen. Gary Peters, D-Michigan, that expanded the advisory committee to include farm and local government organizations and representatives.

“Rural America deserves a seat at the decision-making table, and farmers across Michigan must have access to every opportunity to utilize drone technology to improve their business,” Peters said in a prepared statement.

The primary use of drones is surveying and determining a plants’ health by the color of its leaves. Farmers can tell much about a crop based on this data, researchers say.

Goodwin’s team is working with a drone that carries cameras that gather 10 times as much data as earlier drones. Researchers can view over 500 color spectrums to find the best one for an application. Identifying emerging diseases and novel insect infestations are two applications for this technology, Goodwin said.

The industry is in its infancy and farmers are discovering new applications daily, Dodde said.

Getting nearly instantaneous measurements is an improvement over the old system of sending an army out into the field with measuring sticks and a tally counter, she said.

This is especially true during a nationwide Christmas tree shortage, which gives the farm an advantage over the competition.

“In our industry, you sell a tree based on how tall it is,” Dodde said. “So it’s really helped, especially right now where supply of Christmas trees are tight.”