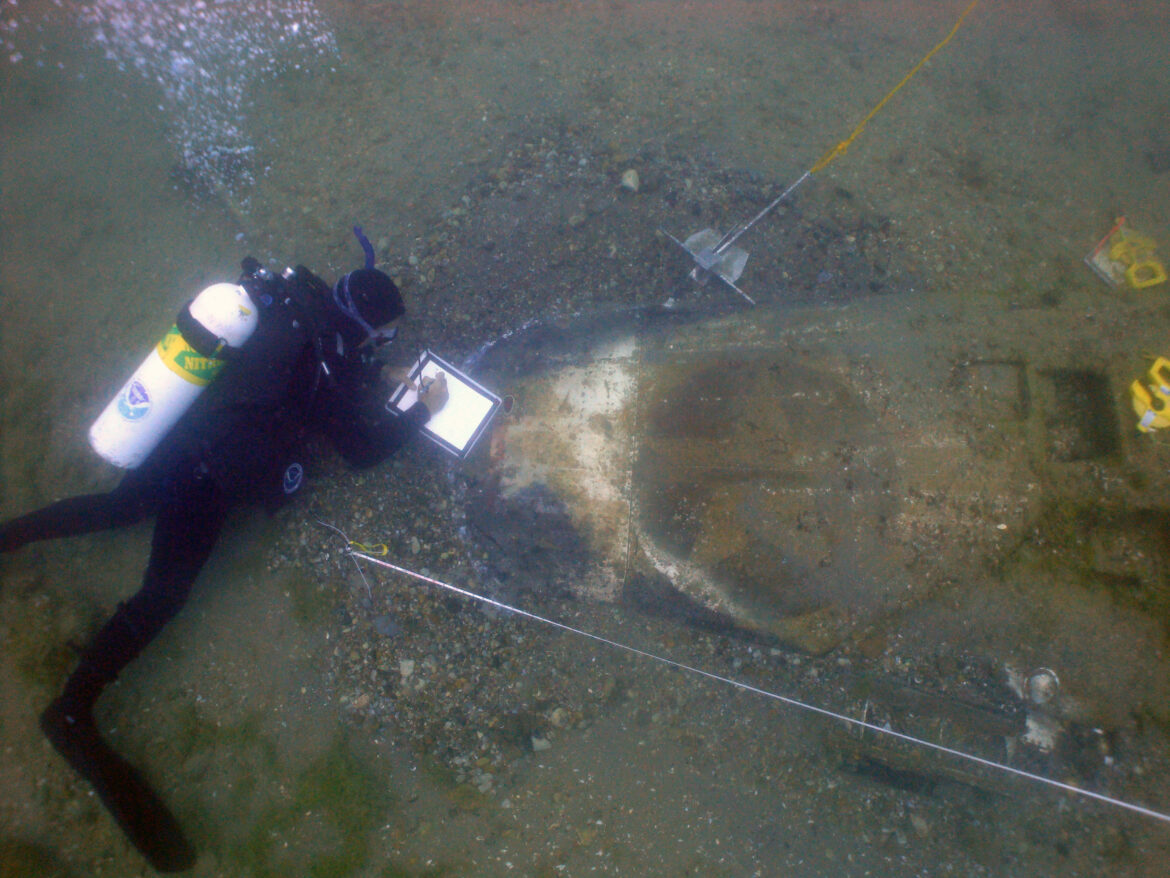

A scuba diver explores the wreckage of the lost P-39Q Airacobra at the bottom of Lake Huron. Image: Erik Denson

By Yue Jiang

Capital News Service

A World War Two fighter plane that was lost in a training accident in the 1940s will be recovered and displayed, according to Wayne Lusardi, a state maritime archaeologist at Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, an underwater preserve in Lake Huron.

The airplane is a P-39Q Airacobra built by Bell Aircraft Co. of Buffalo, N. Y. And it crashed in April 1944 with Lt. Frank Herman Moody, a 22-year-old Tuskegee Airman, flying it. The Tuskegee Airmen were the U.S. Army’s first Black military aviators.

Lusardi said the U.S. Army Air Corps operated a military base at Selfridge Field in Mount Clemens, near Detroit, on Lake St. Clair, where Moody took off from.

“It was flying in formation with four aircraft in total and left Selfridge Field. They headed north up over Lake Huron to conduct gunnery practice. And that’s when the accident occurred.” he said.

Moody died in that accident and his body was found a couple of months later at the mouth of the St. Clair River in Port Huron.

Lusardi said it is hard to plan archaeological excavations right now because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but there are projects lined up for August.

One of the big projects is recovering the World War Two plane’s wreckage.

“We found the airplane about six years ago and we’re going to pick it up and take it out of the lake and put it into a museum,” he said.

The first thing archaeologists do before any recovery is map everything on the lake bottom.

Lt. Frank Moody, the pilot who died when his plane sank in Lake Huron in 1944. Image: Wayne Lusardi

“The plane is broken and spread out over a pretty big area of the bottom in Lake Huron, so we have to map where every piece came from precisely,” he said. “We systematically recovered the pieces beginning in 2018 and are planning on recovering the remainder of the aircraft, if life gets back to normal.”

About 200 military aircraft disappeared into the Great Lakes during the war, mostly in lower Lake Michigan, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Lusardi also explained how wreckage is discovered in the Great Lakes.

“People seem kind of amazed. Why couldn’t you find a big shipwreck in the middle of a lake?” he said.

“But the fact is the lake is pretty gigantic, even if ships that are 100 feet in length are still lost out in the lake somewhere, and there are places that just haven’t been looked for yet,” he said.

Some ships left Detroit on their way to Chicago. And they were never seen again.

He said that it’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.

“All the people on the boat were lost. There are no eyewitness accounts. There is no wreckage that has ever been found. And sometimes you just kind of stumble across that,” he said.

A World War II P-39Q Airacobra is the type of plane lost in Lake Huron in a 1944 accident. Image: Wayne Lusardi

The best way to find a shipwreck is to do historic research first and try to narrow down exactly where vessels were lost, Lusardi said.

He said other helpful ways to find wreckage are using information from survivors, Coast Guard accounts and insurance records. For example, those records may show a wreck that sank 15 miles southeast of Thunder Bay Island in Alpena County.

“So you have a pretty good idea of where those vessels went down. And then you can start looking in that area using sonar and other devices to find it,” he said.

According to a recent book by John Jensen, “Stories from the Wreckage: A Great Lakes Maritime History Inspired by Shipwrecks,” (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, $29.95), it is meaningful to study wrecks in the Great Lakes because those ships are like small windows into national history.

Besides the aircraft wreckage, there are other new excavations in the Great Lakes.

Carrie Swoden, the archaeological director of the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo, took part in excavating the Lake Serpent, a small sailing vessel that sank in 1829 on its way to Cleveland from the Lake Erie islands.

She worked with other volunteers to find the shipwreck.

She said Tom Kowalczk, who found the Lake Serpent, is from the Cleveland Underwater Explorers, a nonprofit organization whose membership includes divers, historians and archaeologists.

“Archaeology is never a single-person activity. You need the support of multiple organizations to do big projects,” she said.

Swoden said her museum has worked with the group for about 12 years and helps subsidize some expenses, including gas for its boats, general repairs and equipment.

She talked about how Kowalczk found the Lake Spirit.

“They use a technique called sidescan sonar, which has been used for shipwrecks for about 30 years,” she said, “It looks almost like a torpedo that you tow behind the boat, and it’s hooked up to a computer.”

Based on sonar results, users can see things that stick up above the bottom of the lake Lusardi also explained how their team projects use 3D models to record shipwrecks.

He said they do systematic sweeps with video imagery and then stitch those videos together.

“It gives you a 3D representation of what the wreckage looks like, so it’s a very quick and relatively easy way of documenting shipwrecks by videography,” he said.