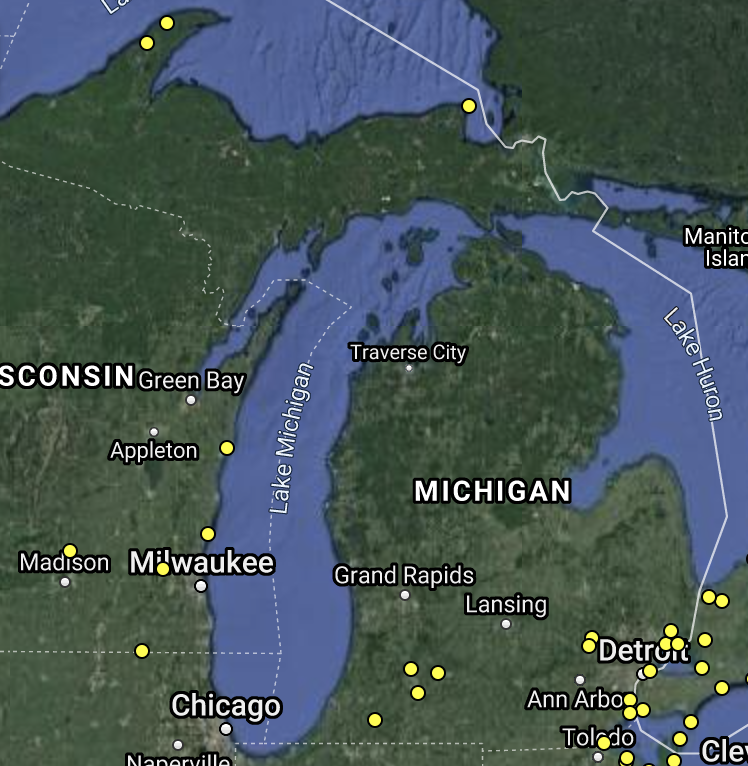

The Motus wildlife tracking system has 16 trackers in Michigan. Image: Motus Wildlife Tracking System website

By Sophia Lada

Capital News Service

Migratory bird patterns are shifting as temperatures increase in North America, leaving birds to find new sources of food and adjust to the warmer climate, according to a new study

Erin Rowan, a senior conservation associate with Chicago-based Audubon Great Lakes and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, said some birds arrive in Michigan earlier than normal because of “false springs,” a consequence of climate change.

“Availability of their habitat and food and how that has played a role in when they depart their wintering grounds and arrive on their breeding grounds is shifting due to climate change,” she said.

Michigan is at the intersection of the Mississippi and Atlantic flyways, which has more than 380 bird species moving through the state every spring.

Flowering plants are blooming earlier as a result of climate change, which shifts relationships between birds and their food sources.

Ruby-throated hummingbirds, for example, are arriving at breeding grounds at a different time than the blooming of their traditional food sources. Studies show that hummingbirds are arriving earlier at their breeding grounds than in the early 1900s.

Hummingbirds are one of many types of birds that must supplement their diet with insects or other food sources because of the changing climate.

Insect-reliant species such as warblers, swifts and swallows are also affected by false springs, Rowan said.

Insects go dormant in the colder weather, which takes away the birds’ food source.

In Michigan, mayflies hatch in May, which is usually a prime time for birds to hatch. With changes in timing, there’s increasing pressure on bird populations to feed their young, Rowan said.

Darren Proppe, a former faculty member at Calvin University in Grand Rapids and the current research director of the Wild Basin Creative Research Center of St. Edward’s University in Texas, was part of a recent study published in the Journal of Avian Biology.

Rich and Brenda Keith of the Kalamazoo Valley Bird Observatory also participate in the research. They’ve had a banding station in Kalamazoo since the 1970s, Proppe said.

At the station, they catch birds every day in the fall and band them to see if they get recaptured in future years.

As temperatures increase, birds are starting to move more north.

That’s causing competition between species that haven’t interacted before, Proppe said.

The average temperature when birds arrived was the same, regardless of whether they arrived earlier or later, Proppe said.

Rowan said geolocators are another way that researchers watch bird migratory patterns, but they are often too heavy to put on small animals like songbirds, bats and insects. They also must be removed by recapturing the animal.

Motus, a wildlife tracking system started by Birds Canada, has 16 trackers in Michigan.

When an animal is tagged, it has a small radio frequency tag so data is recorded when they pass by a radio frequency tower.

Motus is a good way to record data passively and protect wildlife, Rowan said.

Rowan is working on a project that tracks black terns using three Motus towers above Lake St. Clair and one on Belle Isle.

It’s important to track these patterns because “they’re actually going to be staggered based upon ancient patterns tied to their food and habitat availability,” Rowan said.