The number of cases of Lyme disease, caused by bites from the blacklegged tick, climbed from 152 to 404 in Michigan over a four-year period. Pictured is a female blacklegged tick. Image: Joyce Sakamoto, Penn State University

By Lillian Young

Capital News Service

As if we all need another health concern, Lyme disease is creeping up in the ranks of worries for Great Lakes area residents.

Warmer temperatures due to climate change mean a longer breeding season for the blacklegged tick that carries the bacteria — and that means more people become infected, experts warn.

The worsening problem may put more pressure on the pharmaceutical industry to bring a discontinued vaccine back to the U.S. market, one expert said.

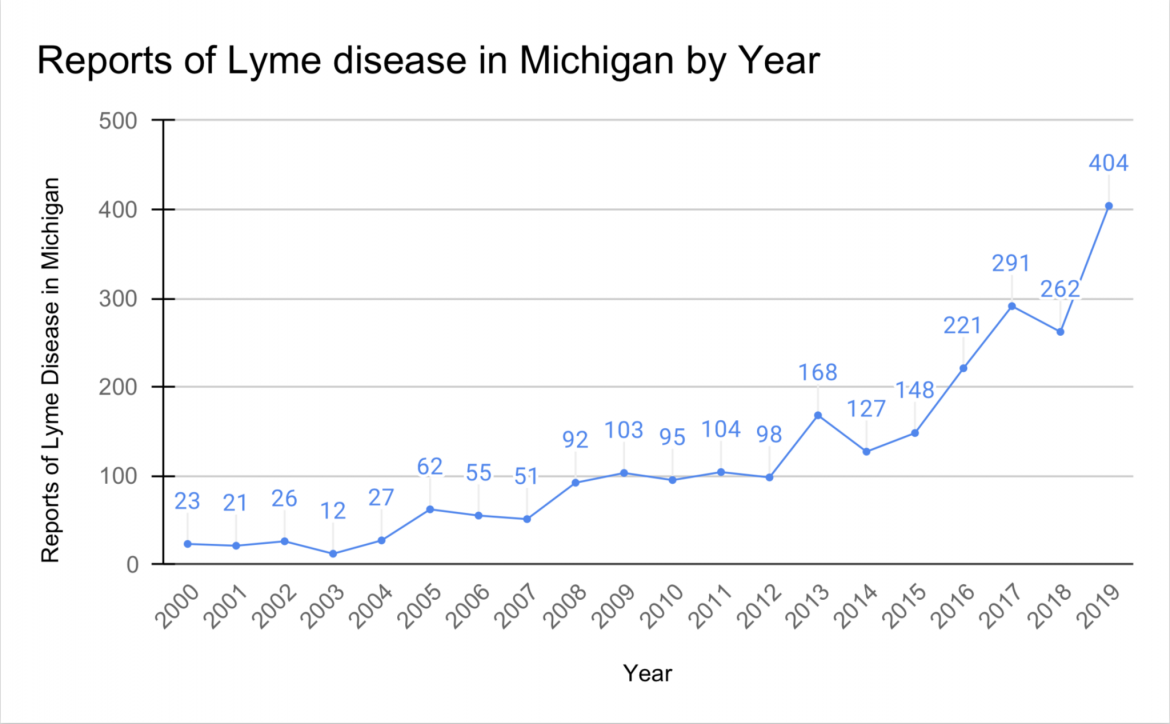

Michigan has seen a sharp jump in cases. In 2019, the state Department of Health and Human Services reported 404 diagnoses, compared with 228 in 2016 and 152 in 2015.

The experience has been similar in nearby states. In 2018, for example, the Ohio Department of Health reported 243 cases of Lyme disease, up from a mere 45 in 2008.

The disease develops after an infected blacklegged tick bites a person. Left untreated, it can lead to severe neurological, cardiovascular and joint problems. If the infection reaches the central nervous system, it can infect the lining of the brain.

Other than the classic bull’s-eye rash, the infection is oddly difficult to identify because it resembles the wear and tear of typical life. Symptoms include fever, headache, joint pain and fatigue, all of which can be easily passed off as the flu.

Given how disguised symptoms can be and the prevalence of ticks in the Midwest, Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne illness — those from fleas, ticks and mosquitoes — in the United States.

Reports of Lyme disease in Michigan by year. Source: 2000 to 2018, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019 Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

According to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cases of tick-transmitted disease in the U.S. have tripled over the past 12 years.

While the CDC estimates cases at around 30,000 per year, a recent study by the agency’s researchers suggests the reality is much worse. “Lyme disease infects approximately 300,000 Americans yearly, eight to tenfold more than the number reported,” the CDC said.

The United States currently lacks a preventative vaccine.

Even more interesting than the lack of a vaccine, however, is that the U.S. used to have one.

Drug company GalxoSmithKlein took its LYMErix off the market in 2002 due to low demand, high cost and misinformation about safety, according to a study by Oklahoma State University professor Matt Motta.

The study, “Could concern about climate change increase demand for a Lyme disease vaccine in the U.S.?” said increasing concern about climate change could contribute to public demand for a new vaccine, which is key to getting LYMErix back in pharmacies.

“Climate change is changing the potential regions of the country where deer ticks can live,” said Motta, a political scientist. His study appeared in the journal Vaccine.

Increasing temperatures in the Great Lakes region where the blacklegged ticks live in wooded and rural areas allows them to propagate longer, Motta said.

This extended time span is leading to a higher tick population and, consequently, a higher risk of contracting the disease.

Researchers at the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments Program recently concluded that annual average air temperatures in the Great Lakes region have increased by 2.3 degrees since 1951. This has lengthened the frost-free season by an average of 16 days a year.

The Ann Arbor-based program predicts that annual average air temperatures will increase by 6 to 11 degrees by the end of the century.

Part of what inspired Motta to explore Lyme disease was facing it firsthand after a hiking trip in Connecticut.

Describing the unpleasant medical treatment that came after his diagnosis, Motta said he was frustrated his dog could get vaccinated for Lyme disease, but he couldn’t.

“I always just assumed that we must not have had the technology, that it escaped us, that there was something about dogs that just made it easier to prevent Lyme disease,” he said. “That’s not at all the case.”

An expert on vector-borne diseases, Roman Ganta of Kansas State University’s Diagnostic Medicine/Pathobiology Department, said, “global warming is there.”

“It’s all interconnected — the expansion of ticks, of white-tailed deer, of increased [tick] population in human areas. If the temperature is optimal, ticks will live,” he said.

A longer period when ticks can propagate due to global warming will cause the rate of Lyme disease infection to also increase, Ganta said.

Ganta said there’s a need for a better public understanding of the relationship between climate change and the expansion of tick-borne diseases.

Many people don’t truly grasp the gravity of the situation, and with the global COVID-19 pandemic underway, Lyme disease isn’t high on the priority list for many, he said.