Ashley Elgin, benthic ecologist at the NOAA Lake Michigan Field Station, discusses the mussels that invade the Great Lakes.

By Kurt Williams

This Spartan Newsroom story is republished with permission.

Denise Purvis’ family began fishing the waters of northern Lake Huron off Manitoulin Island in 1882. Over the years their operation came to expect the unpredictability of a livelihood dependent on the ability to capture wild fish.

Purvis came back to the family business in the mid-1990s after college. Her return home coincided with the arrival of zebra and quagga mussels into the Great Lakes.

The mussels have since become synonymous with the problem of invasive species in the Great Lakes. They’ve colonized the lakes and negatively impacted their ecology.

For Purvis and the dwindling number of Great Lakes commercial whitefish fishers, the fishery has fallen on hard times. Whitefish have been in decline across much of lakes Michigan and Huron, and many scientists and fishers suspect part of the reason is linked to the effects the mussels have had on the lake’s food web.

“The health of our fishery in northern Lake Huron is not healthy whatsoever,” Purvis said.

Lake whitefish decline

Dave Caroffino is a fisheries biologist in Charlevoix, working in the tribal coordination unit in the fisheries division of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

Since 1985, the agency has collected data on whitefish in lakes Michigan, Huron and Superior as part of a legal settlement between the state of Michigan, the federal government and tribal governments.

“The vast majority of the monitoring data starting in 1985 comes from agency staff collecting biological samples from the fish caught by commercial fishers,” Caroffino said. “That data wasn’t used for a lot of stuff. It was kind of general patterns, general trends.”

But now, this decades-long effort is showing clear declines in whitefish; a decline that coincided with the expansion of invasive mussels in the lakes.

The resource agency’s estimates of whitefish biomass in northern Lake Huron dropped 45% from a peak in 1997, when the mussels began to widely colonize the lakes, through 2017, when quagga mussels had succeeded in covering much of the lake bottom.

Invasive mussels and whitefish

Whitefish are native to the Great Lakes. They are bottom feeders, foraging for invertebrates like diporeia, a relative of shrimp that grow to less than 1 centimeter in length. The diporeia live in the sediment of the lakes, feeding on material there, including plankton that settle to the bottom.

Since the 1990s, diporeia numbers have plummeted in most of the Great Lakes.

Because mussels are filter feeders, pulling plankton out of the water, some think the invasives caused the disappearance of diporeia and declines in whitefish.

Steve Pothoven is a fishery biologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Lake Michigan Field Station in Muskegon. He has studied the relationship between diporeia and whitefish.

“Lake Michigan had a spring phytoplankton bloom that would feed the diporeia,” Pothoven said.

Now, mussels feed on the plankton all winter.

In Lake Michigan “that spring bloom is gone now, and that is thought to be a consequence of the mussels,” he said.

Is this enough evidence to blame the loss of diporeia and drop in whitefish numbers on the mussels?

“It seems like it should be really straight forward, if you look at a food web, but it’s been really complicated,” Pothoven said.

In an ecosystem as complex as the Great Lakes, exceptions to the rule can always be found.

Ashley Elgin is a benthic ecologist also at the NOAA Lake Michigan Field Station who studies the benthos, the life living in and on the lake bottom.

Elgin arrived at the lab five years ago. Diporeia could have been a major focus of her research, but they were already nearly gone from the lakes by then. Quagga mussels are now the focus of her research.

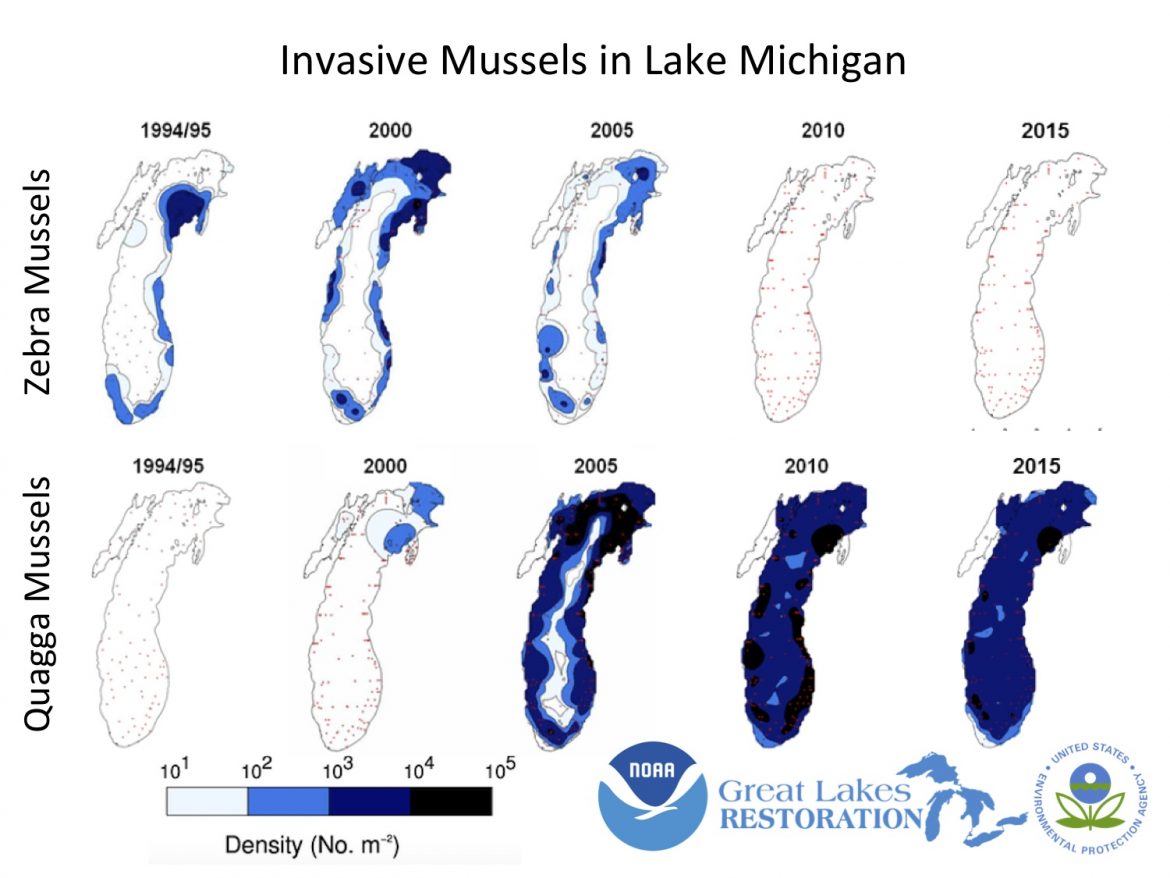

Mapping the spread of zebra mussels beginning in 1994/1995 is followed by an invasion of quagga mussels in 2000 which displaces the zebra mussel from Lake Michigan in 10 years. Quagga mussels now carpet nearly the entire bottom of Lake Michigan. Image: Ashley Elgin, NOAA Lake Michigan Field Station, Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory

To understand what’s happening on the lake bottom, hundreds of feet below the surface, scientists use a ponar grab sampler: a set of metal jaws lowered to the bottom to snap up sediment and the benthos. Researchers sample 150 sites in Lake Michigan and 100 in Lake Huron every five years.

Elgin oversees sampling in southern Lake Michigan.

“We survey 46 sites in the southern third of Lake Michigan and we see them (diporeia) in only one site,” she said.

That site — B4 — historically had thousands of diporeia in a grab.

“Now we get excited if we see 20,” she said.

Diporeia collected from southern Lake Michigan in 2015. This number of diporeia is considered a cause for celebration by scientists studying these animals as they’ve disappeared from large regions of the lower Great Lakes. Image: Ashley Elgin, NOAA Lake Michigan Field Station, Great Lakes Environmental Researh Laboratory

Quagga mussels are never in short supply for Elgin. They’ve even driven zebra mussels out of Lake Michigan and now carpet the lake bottom. She echoes Pothoven in noting the difficulty in laying the blame for diporeias’ collapse solely at the foot of the mussels.

“You had diporeia decline in Lake Huron at the same time as Lake Michigan, when the mussel numbers were very low in Lake Huron,” Elgin said. “Also, Lake Superior has low food levels, but they have healthy diporeia populations.”

Commercial fishers see problems

Jamie Massey has been fishing northern Lake Huron out of St. Ignace for 44 years. He sees a link between the mussels, diporeia and whitefish.

In the past “we’d lift our trap nets and see diporeia all over the deck of the boat and hanging all over the trap nets,” Massey said.

Before the mussels, the water was cloudy and full of life, he said.

“We watched them (the mussels) come in, filter everything out, and slowly but surely we could see the diporeia disappear and the health of the whitefish deteriorate day by day,” he said.

With diporeia scarce, whitefish began to eat quagga mussels, though they’re not as nutritious. Fishers began catching fewer, thinner, less commercially valuable whitefish.

Slime rises in the lakes

As the mussels pulled plankton out of the water, it resulted in dramatic clearing of lakes Michigan and Huron. This allowed sunlight deeper into the lakes, opening new habitats for cladophora, an algae that grows in stringy masses on lake bottoms where fishers like to place their nets.

When cladophora showed up in their nets instead of fish, fishers were surprised.

Denise Purvis recalled colleagues fishing in southern Lake Huron telling her about slime in their nets. This was before cladophora became an issue for Purvis in northern Lake Huron.

“It was the first change in the whitefish fishery” from the mussels, she said.

With cladophora now present around Manitoulin Island, Purvis’ crew has to carefully consider when to go fishing.

“We had to change our fishing: like the way we fished, and what we fished and where we fished,” she said.

On windy days, when the lake is choppy, cladophora gets picked up and trapped in their nets. It can be so bad they’ve got to pull up the nets when they see a windy day coming, losing fishing days.

The cladophora can wreck their fishing gear.

“We used to be able to fish through all that, and go out when it’s rough,” Purvis said.

Purvis is lucky. The company also sells fish wholesale to buyers such as large grocers. But changes in Lake Huron, from the mussels and diporeia, to cladophora and an imbalance in predator fish numbers, have altered operations at Purvis Fisheries.

“What’s changed for us to stay in business, now we have to buy a lot of fish that we never bought before,” Purvis said.

“Now I spend my whole time in the spring, right now, looking to people to buy fish. I have a harder time keeping employees and keeping those guys employed.

“My company in the end can still make money,” she said, but her employees who do the fishing can’t.