Icebreakers U.S. Coast Guard cutter Bristol Bay and Canadian Coast Guard ship Samuel Risley meeting on the St Clair River January 18 2018. Image: Canadian Coast Guard.

By Kaley Fech

When you’re traveling on the Great Lakes in the winter, it’s not just the cold temperatures that cause problems with ice.

The wind, too, wreaks havoc.

“In 2014, I was on an icebreaker on Lake Superior in March and the ice was very thick,” said George Leshkevich, a physical scientist with the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory in Ann Arbor. “We were opening up the ship track for the opening of the shipping season and it took us a day just to get through Whitefish Bay.

“We started making our way from Whitefish Point over to the Keweenaw,” he said. “We didn’t make very much headway because when the icebreaker opened a track up, the winds would close it up behind us.”

Challenges like that keep the U.S. and Canadian Coast Guards busy on the Great Lakes in the winter.

“It’s really an area where there’s a huge amount of collaboration between the U.S. and Canadian Coast Guards,” said Carol Launderville, communications officer for the Canadian Coast Guard on the Great Lakes.

The two services renewed their decades long icebreaking partnership last January with a new memorandum of understanding

The waters of lakes Superior, Huron, Erie and Ontario that are closest to Ontario are Canadian. Those closest to Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York are U.S. waters, said U.S. Coast Guard Lt. Blake Bonifas.

Lake Michigan is wholly in the U.S.

And just like the water they share, the two countries share icebreaking duties, Launderville said. Sometimes Canadian ships clear routes in American waters and vice versa.

And they swap personnel so that the two Coast Guards become familiar with each other’s procedures.

Icebreaking is critical for Great Lakes shipping.

“This last winter, the estimated economic value of the cargo that we were able to help move was valued at $875 million, Bonifas said. “That’s economic activity that wouldn’t exist had we not been able to provide some kind of icebreaking service.”

While there are fewer ships on the Great Lakes in the winter, shipping continues year-round, so it’s important to keep the routes clear, Launderville said.

Members of the Lake Carriers’ Association, based in Cleveland, stop only when the Soo Locks close in mid-January. They resume when the locks reopen at the end of March.

“We ship full bore right up until the locks close and then again when they open,” said Thomas Rayburn, director of environmental and regulatory affairs for the Lake Carriers’ Association.

This means they operate during the ice season, which typically begins in mid-December and continues through April.

“Icebreaking resources are absolutely critical for us to keep moving,” Rayburn said.

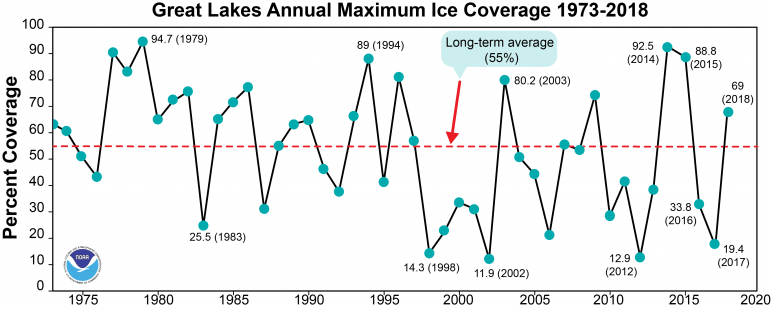

Average ice cover on the Great Lakes from 1973-2018. Graphic: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory

In 2014, ice cover on the Great Lakes reached 92.5 percent, Leshkevich said

“We haven’t seen that kind of ice cover since 1979,” he said.

The next year was also fairly severe, when ice covered 88.8 percent of the Great Lakes

But don’t let those two years of severe ice cover fool you.

“As a whole, when you look at our period or record from 1973 to the present, ice cover on the Great Lakes has tended to decrease over the years, especially since 1997,” said Leshkevich, whose lab is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The longterm average ice cover for the Great Lakes is 55 percent. And the longterm trend is toward less coverage, despite occasional variations. There are more instances where maximum ice cover was above that average prior to 1997 and more instances where ice cover was below it after 1997, Leshkevich said.

Ice cover in 2016 only reached 33.8 percent, and in 2017 it dropped to 19.4 percent, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In 2018, maximum ice coverage went back up, reaching almost 70 percent.

“Ice formation on the Great Lakes can be very dynamic,” Leshkevich said.

Air temperature is one the biggest factors that dictates ice cover, because it affects the water temperature, he said.

“The climate and the air temperatures make a large difference,” Leshkevich said. “If for whatever reason we’re seeing those warming over the years, then that’s going to have an effect on the ice cover.”

Wind is another important factor, he said. If it’s windy and the water is roughened up, it’s less likely that ice will form. Once ice has formed on the lakes, wind can move it and cause shipping problems.

The Canadian Coast Guard has two icebreakers on the Great Lakes, but if needed, it can bring in additional ships, Launderville said.

The U.S. Coast Guard has nine. The number is adequate, but the fleet is aging, Bonifas said.

“A lot of our icebreakers have exceeded their service life,” he said. “Many of them were built in the 70s, so they are getting towards their 50th birthday.

“We see a lot of missed cutter days due to maintenance issues and repairs to keep these older ships running,” he said.

There are no immediate plans to modernize the Great Lakes fleet. Priorities are elsewhere.

“We only have two functioning polar ice breakers that operate in Antarctica and the Arctic, so the focus is going towards building another one of those,” he said.

During the most severe winters, the U.S. Coast Guard’s partnership with the Canadian Coast Guard is not only extremely beneficial, it’s necessary, Bonifas said.

Icebreaking on the Great Lakes is a truly binational effort, Launderville said. “The two Coast Guards really work as one.”