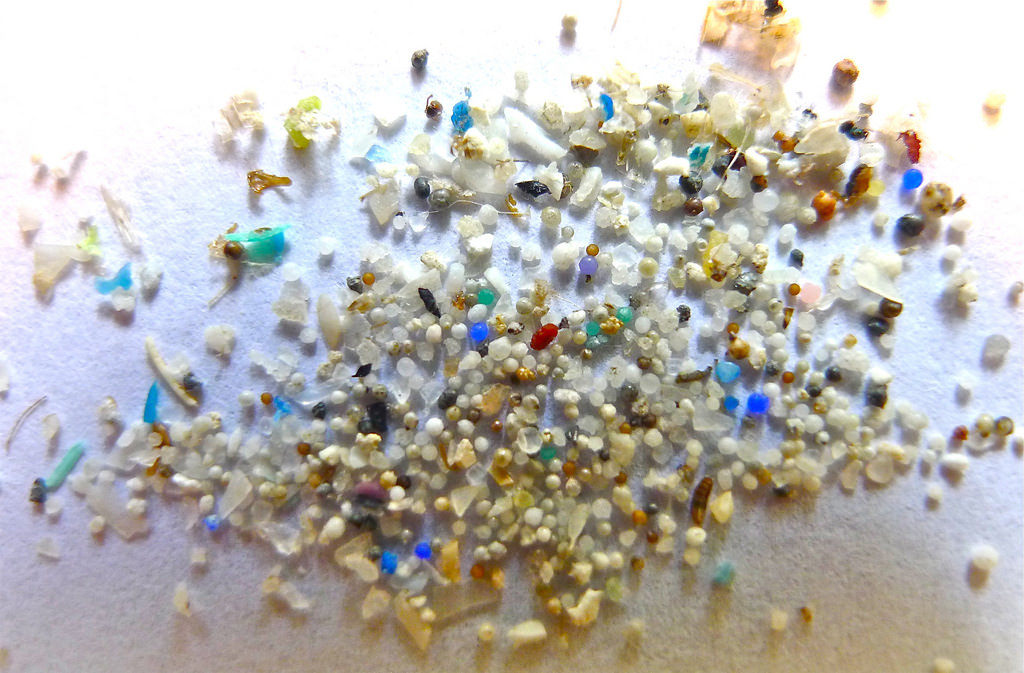

Plastic contaminating lake and beach sediment is an increasing Great Lakes concern. Image: 5Gyres, courtesy Oregon State University.

By Anntaninna Biondo

Out of sight, out of mind.

That might once have been the motto when disposing of plastic, but now it’s washing up on Great Lakes shores like a message in a polyethylene terephthalate bottle.

It’s not water bottles or plastic bags, but what’s left of them.

These tiny pieces of plastic, or microplastics, range from the size of a sesame seed to a lentil, said Patricia Corcoran, who studies sediment as a researcher at Western University in Ontario.

Corcoran found more microplastics on Lake Ontario than on Lake Erie. She attributed the difference to population density and proximity to plastic producing factories.

“You probably wouldn’t notice them a whole lot except where they tend to accumulate, like if you get to a beach where there are thousands of them,” she said.

The pellets are the larger class of microplastics – think lentils – and take years to end up among the sand. At one point, the pellets were melted together and molded into maybe a ketchup bottle, Corcoran said. Over time they break down until smaller pieces remain.

Plastics and pollutants threaten Great Lakes wildlife and human populations.

The concern comes from how pollutants in the water adhere to the microplastics, Corcoran said.

“If something were to eat a pellet, that could potentially create an issue for pollution inside a fish for example.”

The amount of microplastics showing up on the shores and on the surface is likely to increase, she said. Because the tiny particles are coming from larger items that break down like bags or clothing, it only makes sense to find the quantity spiking, especially as population increases and more people demand plastic.

Microbeads, however, are expected to be on the decline, Corcoran said, given a recent ban in the U.S. and Canada.

The tiny spheres found in items like body washes and toothpaste are notorious for polluting oceans and lakes. Unlike the pellets or fibers, they stay on the surface of water, Corcoran said.

As far as ways to reduce plastic use, prevention is the ultimate solution, said Sarah Lowe, the Great Lakes coordinator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“It’s helping educate others by raising awareness of the problem which can then hopefully help change behaviors,” she said.

A lot of Great Lakes residents haven’t heard about the issue, Lowe said.

“You see litter on the side of the roads but you don’t always make the connection that it’s in the water too so there’s a little bit of surprise there,” she said. “Then it leads to more questions from them like, ‘what can I do to help?’”

Corcoran said she makes simple swaps to reduce her plastic use all together. Using ceramic dinnerware, wearing mostly cotton and refusing plastic straws might seem insignificant, but if everyone followed suit, “we could do so much,” she said.

Lowe read Corcoran’s study and said she’s glad people are looking into this.

“It’s looking more into the full picture of the problem,” Lowe said. “A lot of research has been on the floating plastics, and we’re now getting more people interested in plastics that are sinking to the bottom in sediment like in this paper.”

Researchers like Corcoran are important because questions like these are only now being addressed, Lowe said.

Corcoran is certain that residents can influence positive change.

“We could really reduce the amount of plastics we use if we just put our minds to it.”