By Anntaninna Biondo

A recent International Joint Commission poll revealed stark differences between indigenous and non-indigenous people about threats to the Great Lakes.

The poll of about 4,000 people asked about their attitudes toward regulations on the Great Lakes, the biggest threats to them and whether there even were threats.

For the first time the survey included 300 Native Americans and other indigenous groups of people proportional to the region’s population.

“Traditional indigenous knowledge has a lot to offer as far as how to approach environmental issues and so we really wanted to try and reach out to that,” said Sally Cole-Misch, a public affairs officer for the binational commission that works with the United States and Canada to manage shared lakes and river systems along the border.

“By adding this additional demographic data, it really allowed us to see more of the breadth of diversity that makes up the basin,” said Kelsey Leonard, engagement workgroup co-chair for the Great Lakes Water Quality Board, which partnered with the commission on the poll.

Among the differences is that 20 percent of the non-indigenous respondents didn’t know where their drinking water comes from, but only about 1 percent of indigenous people were not sure.

It comes down to lack of education and the public taking their water for granted, Cole-Misch said. Unlike on Native American reserves, urban and suburban communities usually don’t have to deal with wells or septic systems.

“Water comes out of the pipe and people don’t really think of where it comes from or where it goes,” she said.

The poll asked respondents to choose the most significant problem facing the Great Lakes. There were 17 choices, including invasive species, pollution, climate change and algal blooms.

The most common answer from non-indigenous respondents was “Don’t know,” with 25 percent. But only 9 percent of indigenous people indicated they didn’t know. The response they gave most often – 21 percent of the time – was endangered fish species.

Data source: The Great Lakes Water Quality Board, IJC.org

Leonard said she was unsurprised by the difference in answers.

There might be a larger issue at play concerning knowledge disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous respondents, she said.

“I think it really stems from different world views where one sees the environment,” said Leonard, a Native American woman. “There was a level of reciprocity and responsibility that as individuals, they felt and articulated in their poll responses.”

She knows that environmental issues are important in indigenous communities.

“It’s very beneficial to reaffirming that lifestyle and those concerns for indigenous nations and people in the basin,” she said.

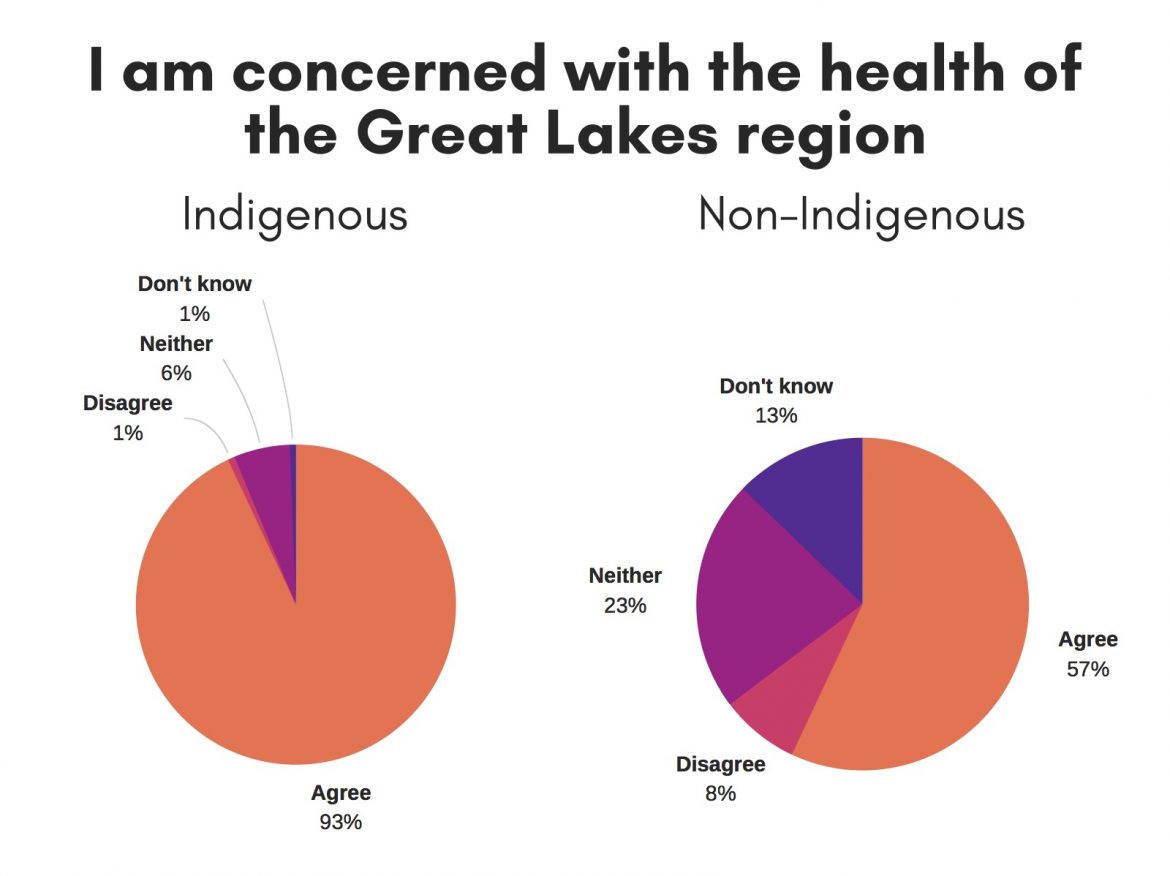

According to the poll, 93 percent of indigenous respondents were concerned with the overall health of the Great Lakes. In contrast, only 57 percent of non-indigenous respondents said that they were concerned.

It’s because indigenous communities have a perspective that is connected to nature and the environment, Cole-Misch said.

“That’s a core part of their First Nations’ or tribes’ philosophies,” she said.

Data source: The Great Lakes Water Quality Board, IJC.org

Leonard always knew that indigenous communities were concerned about the Great Lakes, but now this poll has greater implications for those communities, she said.

“We now have data to support some of the more common knowledge from the indigenous perspective around differences in world views,” Leonard said.

And it makes sense that the indigenous respondents are more worried.

“Their cultural survival and political existence is directly tied to the health of the lakes,” she said.

An unexpected finding was that half of indigenous respondents were willing to protest, vote or lobby to protect the Great Lakes. Only about 10 percent of non-indigenous respondents were willing to do the same.

Many indigenous peoples grow up being politically active, Leonard said.

“Our existence as indigenous peoples is a resistance, so I think that it is conditioned within us as a community that our voices are heard and that we are contributing in whatever way we can to ensure the protection of this planet for future generations,” she said.

Data source: The Great Lakes Water Quality Board, IJC.org

Indigenous communities are by definition, a political movement. Settlers forced them to assimilate to other cultures and religions, the act of leading a life where one is still practicing traditional indigenous ways means that they are resisting against their oppressors.

In the last several months of 2016, thousands set up protest camps at the Dakota Access Pipeline near North Dakota’s Standing Rock Sioux Tribe reservation, according to the New York Times. The pipeline has oil flowing through it today, but it started a conversation and a well-known movement across the continent.

Half of non-indigenous respondents said there are too few regulations protecting the Great Lakes. How many indigenous people thought that way?

You can almost double that.

Data source: The Great Lakes Water Quality Board, IJC.org

That difference also speaks to Leonard’s perspective, Cole-Misch said.

These indigenous communities are not only raised to be stewards of the planet, but indigenous peoples can’t afford to ignore water quality, she said.

Recognizing our roles as stewards is important, Leonard said.

“It doesn’t matter what background you’re from, it’s about being a good citizen to this planet,” she said.

Related story: Changing climate linked to changing species