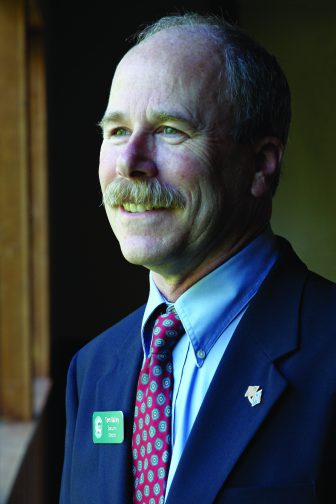

Tom Bailey

By Kaley Fech

When Tom Bailey was just 17 years old, he flew to Washington, D.C. and testified before the Senate Interior Committee on wilderness policy for Isle Royale.

Bailey had learned that a proposal by the National Park Service would exclude large areas of Isle Royale National Park from designation as wilderness. He became a member of the Michigan Student Environmental Coalition and worked with a group of people to create an alternative that included the entire island.

That was in 1972. Four years later the proposal was approved and signed into law.

Now, after decades of working to protect the outdoors, he figured he had a lot of knowledge to share.

So he wrote a book.

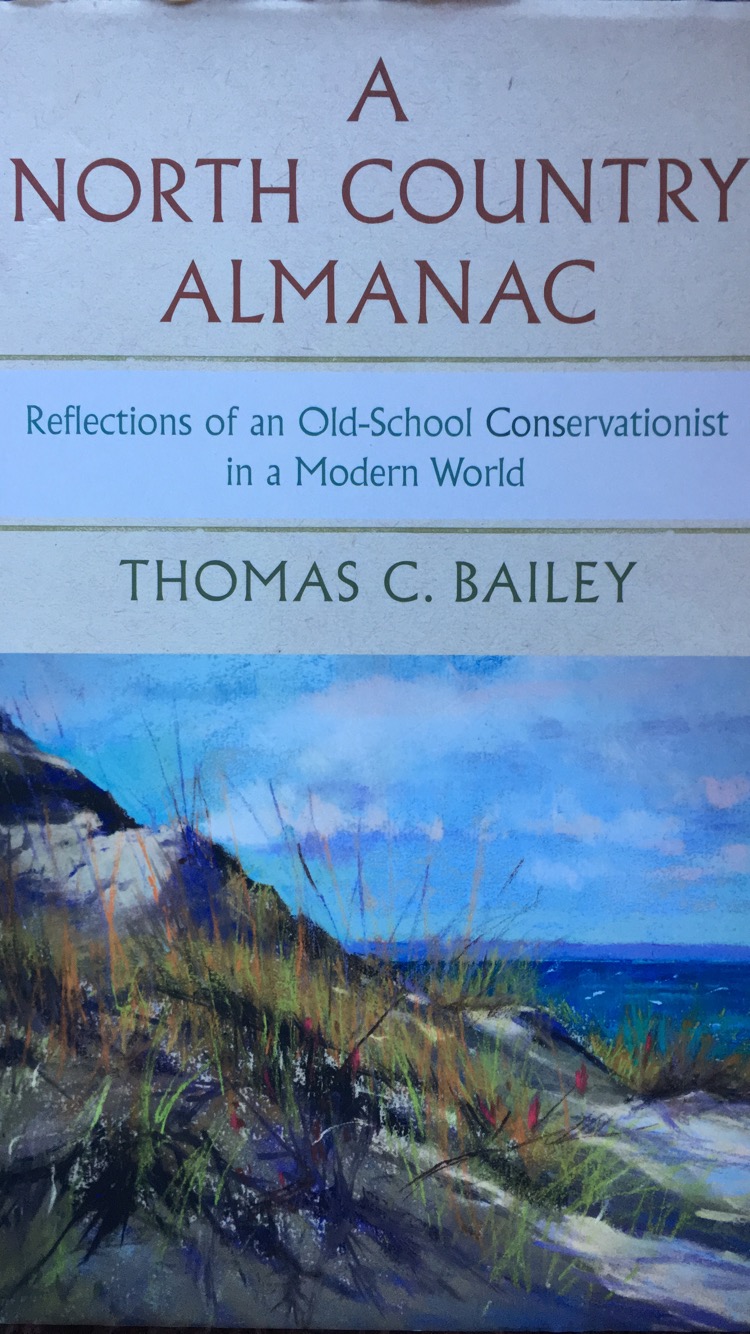

“A North Country Almanac: Reflections of an Old-School Conservationist in a Modern World,”(Michigan State University Press, $24.95) is a collection of essays that explore aspects of conservation and Bailey’s affinity for the outdoors.

“I grew up outdoors,” he said. “Being outdoors has been a natural thing for me.”

Two years after he testified, he became a park ranger for the Na tional Park Service. He spent three summers as a park ranger on Isle Royale and in Grand Portage, Minnesota.

tional Park Service. He spent three summers as a park ranger on Isle Royale and in Grand Portage, Minnesota.

“I just love the place – its spectacular wildness, its beautiful scenery,” he said.

“That north country atmosphere with the moose and the wolves, it was heaven on earth to me. But it was also a fulfillment of a dream to wear that Park Service uniform.”

And the experience knitted him closer to his father who was a wildlife biologist, he said.

After his time as a park ranger, he worked for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources for several years before moving to the Little Traverse Conservancy in Harbor Springs, where he remained for 34 years until his retirement this past August.

“The conservancy protects land the old-fashioned way,” Bailey said. “We own it. Rather than being an advocacy organization or some sort of pressure group, the Little Traverse Conservancy involves people putting their money where their mouth is and where their heart is to protect land in northern Michigan.”

Bailey was a leader who had a special gift for walking the non-partisan line in a field of work that is important, physically and spiritually, to everyone: the protection of the natural world, said Anne Fleming, director of communications and membership at the Little Traverse Conservancy.

“He had a big picture mind and always kept gratitude at the forefront,” she said.

One of the essays in his book discusses scientific studies that show the importance of nature for intellectual development, in addition to the spiritual and emotional benefits so many people get from the outdoors.

Bailey has a fundamental belief that nature is good for people. He says he often reflects on a line from a poem by Walt Whitman that “the secret of making the best person is to grow in the open air and to eat and sleep with the earth.”

This belief is one of the things that prompted him to pursue a career in conservation.

“It’s not just science and survival, it’s for our souls,” he said. “I think the best hope for humanity is that we maintain a certain humility before nature and that we maintain a certain reverence for the natural world that enables us to see ourselves and our activities in perspective.”

Several of the essays in his book reflect his perspectives on hunting and its role in conservation. Hunting is often a highly debated topic, and he uses an example from shamanistic culture to showcase the need for both hunters and nonhunters.

“What a shaman would say in the native culture is that each of us has a spirit guide and a spirit animal,’ Bailey said. “If someone’s spirit is a deer spirit or a rabbit spirit, they’re not a hunter, they don’t understand it, and they fear hunters.

“On the other hand, if someone has a wolf spirit or a bear spirit, they are by nature a hunter. Every spirit needs to be left to its own fulfillments. There’s room for everyone.”