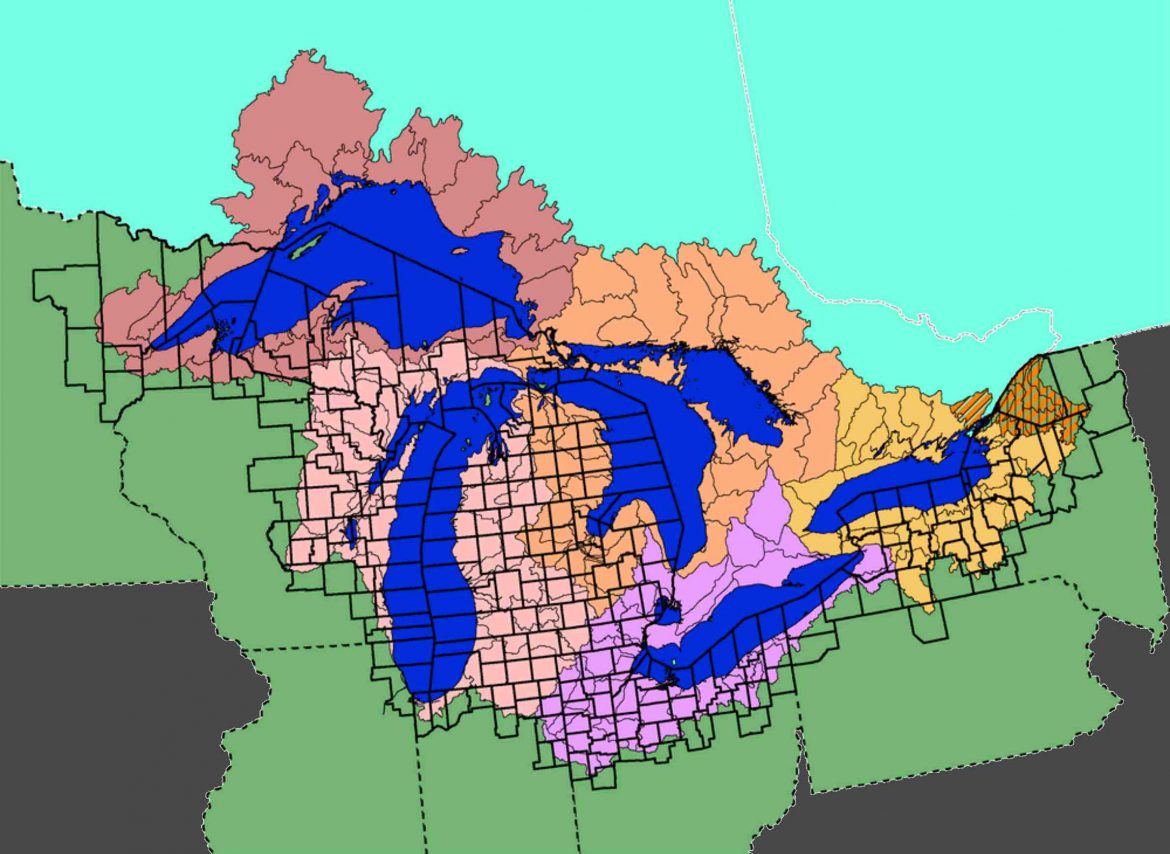

The Great Lakes Basin covers eight U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Image: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

By Scott Gordon

This story originally appeared on WisContext and is republished here with permission.

Wisconsin has yet to wrap up one big conversation about how it uses Great Lakes water, and is already embarking upon another. The city of Waukesha secured permission in 2016 to use about 8 million gallons per day from Lake Michigan to replace its overburdened, radium-tainted groundwater supply. Less than two years later, Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer Foxconn, working through the Racine Water Utility, is seeking permission to use some 7 million gallons a day from the lake for an LCD screen factory complex in the village of Mount Pleasant.

In following both the Waukesha and Foxconn bids for Lake Michigan’s water, it’s easy to get turned around. An especially tangled point is where the rules of the Great Lakes Compact begin and the discretion of the Wisconsin Legislature and state regulators begins.

Eight states and two Canadian provinces on the Great Lakes reached a binational agreement in 2005 about how to use and protect one of the world’s great freshwater resources. On both sides of the border, legislators subsequently went to work creating laws to implement that agreement. The Great Lakes Compact is the legally binding part of the bargain for the United States, which President George W. Bush signed into law in 2008. Across the border in Canada, the provinces of Ontario and Quebec modified their own laws surrounding Great Lakes water use to be in line with the binational agreement.

Before the Great Lakes Compact was enacted, though, Congress had to pass it. Before that national phase, the deal was ratified in the legislatures of the eight Great Lakes states: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Some of the work of enforcing the Compact is at a regional level, with the eight states negotiating with each other and, if called for, convening a vote of their governors. But the rest of the enforcement is delegated to the states themselves to handle internally; state legislatures and regulators are charged with making sure standards of water use and environmental quality are met within their own borders.

No state has the power to unilaterally alter the terms of the Compact, but they have some discretion as to how specifically they enforce them. With thousands of cities and industrial users within the Great Lakes Basin withdrawing and discharging water, that work is spread out among multiple agencies. In Wisconsin, the Department of Natural Resources handles implementing the Compact, and is also largely responsible for enforcing federal environmental regulations at the state level. And in addition to enforcing the Compact and federal law, the eight signatory states each have to craft environmental regulations that make sense for their own specific situations.

Regulation of Great Lakes water use is regulated by the overlapping terms of the Great Lakes Compact alongside state and provincial laws. Image: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

So, where does the Great Lakes Compact end and state law begin? That isn’t so clear-cut. Wisconsin had to ratify the Compact like its seven fellow Great Lakes states, so effectively its terms are actually encoded into Wisconsin’s state statutes (281.343), in addition to existing as a regional agreement enshrined in federal law.

Different sides of boundary lines

In the parlance of the Great Lakes Compact and regional water politics, both Waukesha and Foxconn-via-Racine are asking for what’s known as a diversion — essentially, taking water out of the Great Lakes Basin. The basin line is a hydrologic boundary, which means that water on one side cannot cross to the other without human intervention. It’s also the boundary around which the rules of water access in the lakes revolve.

Under the terms of the Compact, it’s all about where a user is in relation to that line, and it creates essentially three different kinds of users:

- If a city or industrial user is taking water from the Great Lakes but not sending it anywhere outside of the Basin, they’re more or less entitled to that use, and subject to the same state-level permits and regulations as anyone else distributing drinking water. and/or discharging wastewater.

- A public water utility whose service area is straddling the basin line — partially in and partially out — is also allowed to use Great Lakes water, but must adhere to a few broad standards. Additionally, if this use creates a new consumptive use of 5 million gallons per day or more, it can trigger a non-binding regional review from the other Great Lakes states. It’s this category in which Racine’s proposal to send water to the Foxconn factory falls, at least according to the company and city’s water utility. A private user, like an industrial facility, cannot directly divert water out of the Great Lakes Basin. Foxconn contends that it’s following the Compact’s and state’s rules because it’s purchasing water from a public utility, and because the infrastructure that will be built out to bring it the water will also benefit other users along its route. Opponents of the Foxconn diversion are crying foul, saying it exists for the benefit of a private company. Again, it’s utterly common for public utilities to sell water to industrial users as well as to households, but there’s little dispute that state and local officials are pursuing this diversion at Foxconn’s behest, and putting up a lot of public money to do it.

- A water utility whose service area is wholly outside the Basin, but inside a county that straddles the basin line, is not entitled to the water. However, the utility can apply for a diversion if it agrees to meet somewhat stricter conditions, and if the governors of all eight Great Lakes states unanimously approve it. Among other things, the utility must convince the eight governors that it doesn’t have a reasonable alternative for meeting its water needs. Waukesha is an example of this type of use. In fact, Waukesha is the first-ever straddling-county community to seek access to Great Lakes water under the Compact. That’s one reason Waukesha’s diversion was so controversial and so long-fought — it didn’t just impact that city or the Milwaukee region, but it also set a precedent for how the Compact might be applied the next time a water utility asks for a diversion outside the Great Lakes Basin.

On a more obscure note, the Great Lakes Compact also provides for “intrabasin transfer.” That’s a term for moving water from one point in the Great Lakes Basin to another.

One obscure aspect of the Great Lakes Compact is a provision addressing the potential transfer of water between locations within the Basin. Image: Environment Canada

For instance, it would apply if for some reason a utility proposed piping Lake Michigan water to a community within the Lake Superior section of the Basin. But “that hasn’t popped up at all yet,” said Pete Johnson, deputy director of the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers, which works to encourage coordinated economic and environmental policy in the region, and precedes the Compact.

Straddling state power and regional water politics

The biggest policy distinction among different types of Great Lakes water users is between the straddling communities and the straddling-county communities. The former type of user might be taking some water out of the Great Lakes Basin, but it’s largely up to the state in which it’s taking place to regulate and approve it. The latter type of user must make its case to a body of eight governors charged with enforcing a legally binding multi-state agreement enshrined in federal law.

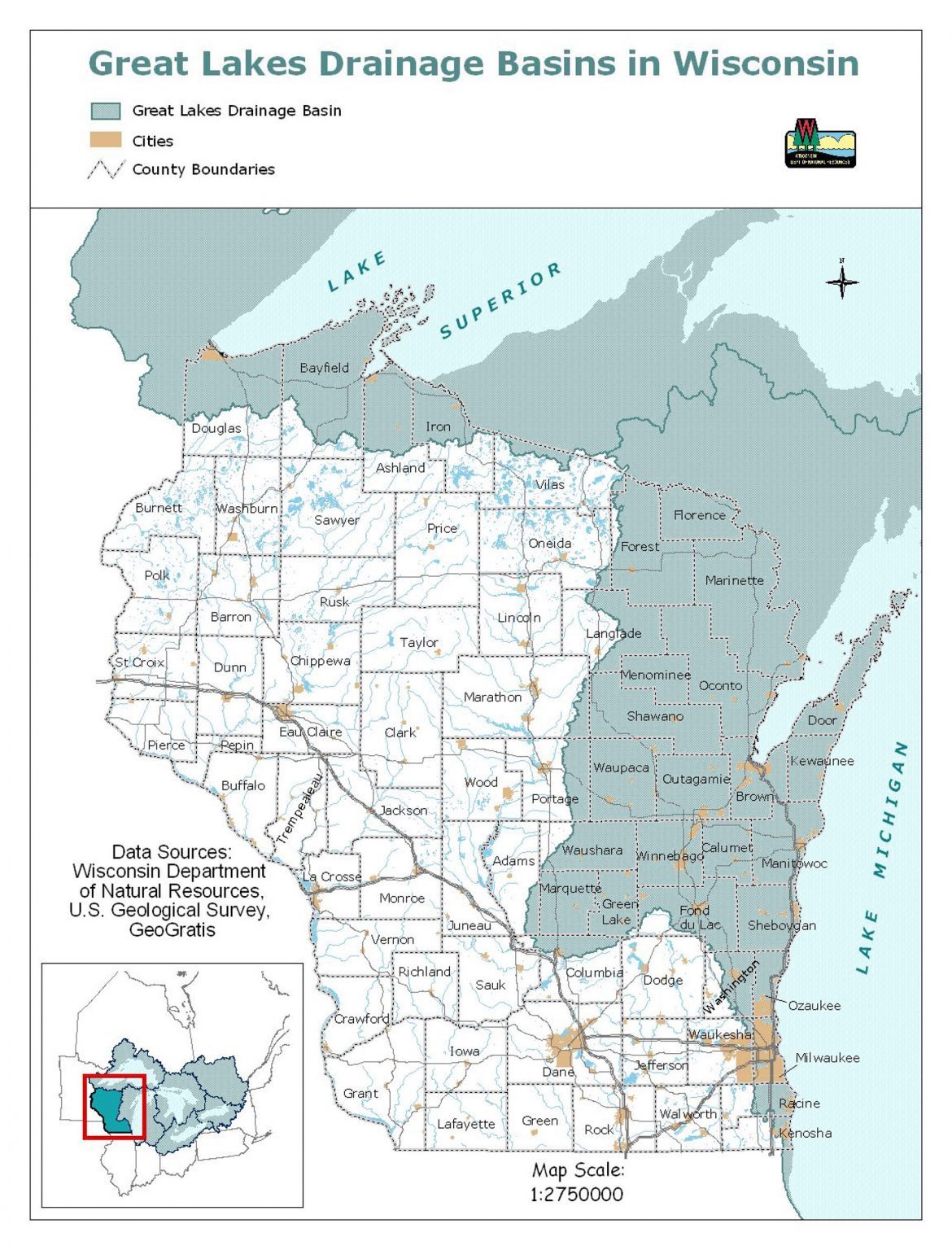

Racine and Kenosha counties straddle the border of the Great Lakes Basin. Image: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

In the former case, the Great Lakes Compact still very much applies, but it’s essentially delegated to the states to enforce it.

“The Compact is written so that the originating state has the review authority for that, and so there can be some comment provided, but there’s no review or approval process from any of the regional bodies,” said Lawrie Kobza, a Madison-based lawyer who has worked with Wisconsin water utilities including Racine’s (but has not dealt directly with the Foxconn matter).

One further wrinkle is though the terms of the Compact are enshrined in the statutes of each individual Great Lakes state, they’re a little different in each. These distinctions exist because each state has different environmental regulations and different methods for implementing its share of the Compact, said Adam Freihoefer, who heads the water use section at the Wisconsin DNR and is in charge of overseeing the permitting process for the Foxconn diversion. When asked how Foxconn and Racine’s permit would differ from any other wastewater-discharge permit the state issues, he explained that it really wouldn’t.

“They have to return the water and they have to meet the water quality standards in the water that’s being returned,” Freihoefer said.

“If this was all moved east, none of this would be an issue,” he added.

Most of eastern Racine County is located within the Great Lakes Basin. Image: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

As the DNR seeks public comment on the Foxconn permit and holds public meetings, the most common concern is that Racine would essentially be diverting massive amounts of water to serve a private for-profit company.

“It’s something legally we need to look at…I don’t really have any answer on where we sit with that,” Freihoefer said.

Kobza takes the view that utilities serving water to industrial users is an environmental plus.

“That’s typical and frankly that’s better, because you’ve got kind of a unified provider coordinating all the water uses within the state, where you end up having problems,” Kobza said. “Then you have conservation requirements and someone who can impose them.”

Regional recourse

The Racine Water Utility isn’t using anywhere close the amount of Great Lakes water that it already has permission to use, and will still be well within its rights even if it does add 7 million gallons more per day for Foxconn. The manufacturing complex plans on an eye-popping 39 percent consumptive use — meaning just 61 percent of the water it takes would be returned to the Great Lakes Basin. But this level does not create 5 millions per day of new consumptive use, so it’s still within the state’s discretion to allow under the Great Lakes Compact.

What if Foxconn gets its permission to use 7 million gallons per day from Racine — including about 2.7 million gallons per day of consumptive use — gets its manufacturing operations going, and then decides to ramp things up and ask for more water?

Pete Johnson, of the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers, said that 2.7 million gallons per day of consumptive use previously approved would be counted toward the Compact’s 5 million gallon threshold, along with whatever amount of additional consumptive use any future water request would create. That is, as long as those requests happen within 10 years of each other. The language of the Compact clearly states: “Applications for New or increased Withdrawals, Consumptive Uses or Exceptions shall be considered cumulatively within ten years of any application.” It is presumably a safeguard against a user adding a few million gallons of consumptive use here and there, and then claiming in bad faith that it’s within Compact rules.

When new consumptive use does hit or exceed that 5 million gallons per day threshold, again, it triggers a regional review involving all eight Great Lakes states. This review does not provide any legally binding results, but can subject a state to some level of scrutiny and informal pressure from its Great Lakes neighbors.

There are already indications that other Great Lakes states are worried about the depleted and politically constrained Wisconsin DNR’s ability to enforce environmental regulations. The Waukesha diversion agreement received unanimous approval from the eight governors, but Minnesota officials insisted on including language reaffirming other states’ ability to hold each other to account under the compact.

If another state in the Great Lakes Basin becomes convinced that Wisconsin isn’t properly enforcing the compact — whether in the case of Waukesha, Racine (and Foxconn), or any other withdrawal or discharge — it can raise a complaint.

“Any Person aggrieved by a Party action shall be entitled to a hearing pursuant to the relevant Party’s administrative procedures and laws,” the Compact reads.

Johnson explained that this type of complaint would first lead to a review of the issue in question under the administrative review processes Wisconsin’s environmental regulations provide for. If that doesn’t work out to the aggrieved party’s satisfaction, they can take the matter to court. But barring that, a large part of making the Great Lakes Compact work really is up to the individual states, working through their legislatures and environmental agencies.