Fungi grow well in the lab when fed Cheerios. Image: Candace Coker.

By Jack Nissen

A cure to childhood cancer may be hidden in fungus discovered at the bottom of the Great Lakes and nurtured on Cheerios.

While the breakfast cereal came from Walmart, the fungi were found in the Midwest’s own backyard: the bottom of the Great Lakes—which until recently have been hardly touched in the world of fungal research.

“I was shocked when I started doing the background research looking through the Great Lakes, and just thinking ‘holy crap, there’s basically nothing known about this,’” said Robert Cichewicz, a natural products professor at the University of Oklahoma. “That was just mind-boggling. One of the biggest freshwater sources on Earth and no one knew what its fungal component was.

“A whole kingdom of life missing.”

What led Cichewicz and other researchers from universities in Michigan, Illinois, Oklahoma and Texas to suspect the secret to fighting pediatric cancer may be found in this hidden world started more than four years ago.

The National Institutes of Health awarded them $2.5 million to research a cancer cure. The money that wasn’t necessarily intended for fungi research. But both Cichewicz and his colleague, Susan Mooberry, saw cancer-fighting potential in fungi because of its presence in life-saving drugs like penicillin and statin.

“I think they are the most brilliant chemists on earth,” Cichewicz said. “They make amazing molecules for their own purposes of course, it just so happens we as humans can hijack them for other purposes.”

Cichewicz assembled a team that included Mooberry, a pharmacology professor at University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, Andrew Miller, a plant biologist at the University of Illinois, and Mark Luttenton, an ecologist at Michigan’s Grand Valley State University and who is Cichewicz’s former mentor.

Members of the team were each assigned different roles to tackle the unknown Great Lakes regions and learn what secrets they held.

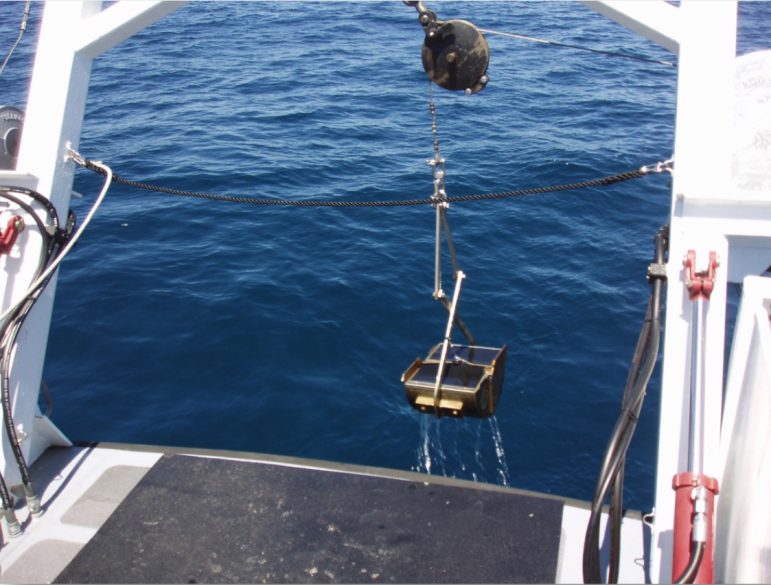

With access to research vessels, Luttenton and volunteers made trips to parts of lakes Michigan, Huron and Superior. They dropped a giant scoop called a Ponar dredge into the lake bed and collected whatever sediment lay at the bottom.

A Ponar dredge collects sediment at the bottom of lakes. Image: Mark Luttenton.

Then the sediment was divided up and mailed to both Andrew Miller and Robert’s Cichewicz’s labs for testing, Luttenton said. There the spores were isolated and grown.

That’s where the Cheerios come in.

“They grow great on it,” Cichewicz said. “They make tons of natural products. The fungi are very happy to be on it.”

The natural products—the chemical compounds found in fungi that are used in medicine—were then shipped to Mooberry’s lab, where she pitted them against cancer cells.

Toxins that kill everything have been studied quite a bit, Mooberry said. “We’re looking at things that have selectivity.”

Sediment collected with the ponar dredge. Image: Mark Luttenton.

The researchers want toxins that kill only cancer cells. After enough testing, they found one—a fungal toxin that eliminates only cancer cells associated with a rare type of the disease that grows on the bones of adolescents.

“We’ve come up with a lead for Ewing’s sarcoma that we’re pretty excited about,” Mooberry said. Lots of work lies ahead, but “even if we don’t discover the next drug, we could discover a target that people can then make molecules for.”

There’s another benefit to the study apart from the laboratory research. Before Luttenton’s digging, 13 fungal species had been identified in the Great Lakes. By the end of his 200 digs, that number had climbed to 460, a boon for the fungi database.

Every time the scoop completed an excavation, several environmental factors were also documented, Luttenton said. Such measures as temperature, depth and available oxygen were recorded in hopes of discovering a pattern to the fungal types growing below.

The question Luttenton said the team pursued: “Can we better predict where we can expect higher fungal diversity, knowing what ecological conditions might be more conducive?”

Despite the optimism, the research has yet to emerge past the discovery stage. The journey toward a marketed cure for cancer is far from certain.

“Our chance is one in a thousand,” Mooberry said. “When we get something we think is really good, it’s still one in a thousand that it will get to the clinics. The bar is very high, but you know, you don’t know until you go out there.”