Andy Morrison

Quagga and zebra mussels covered most of the wreck when it was discovered. Image: Andy Morrison

By Jack Nissen

Ohio is a hotbed for historical preservation, but the state lacked a shipwreck on the National Register of Historic Places until recently.

“The Anthony Wayne is a great example of the kinds of vessels that used to supply Lake Erie in the 1800s,” said Kendra Kennedy, a maritime archaeologist at the Ohio History Connection.

The Anthony Wayne shipwreck’s nomination to the national register ends mountains of research from an unlikely source: a Texas A&M student’s thesis.

Shipwreck hunters confirmed the ship was an old steamboat after its discovery in 2006, said Brad Kruger, a National Park Service cultural resource specialist. “After learning this, I began to do my own research. In 2008 I formed an archaeological survey and worked with volunteers for a four week period.”

The first year of the survey reported the wreckage above the lakebed, most notably its paddle wheels. The following year, Kruger and his team excavated around the wreck to see what the mud was hiding.

“We found a marine engine, one of the earliest examples of one in the entire Great Lakes,”Kruger said. “A fully preserved engine, just under a few feet of mud.”

The Anthony Wayne was about seven miles north of Ohio when two of its boilers exploded. It sunk to the bottom of Lake Erie in 1850.

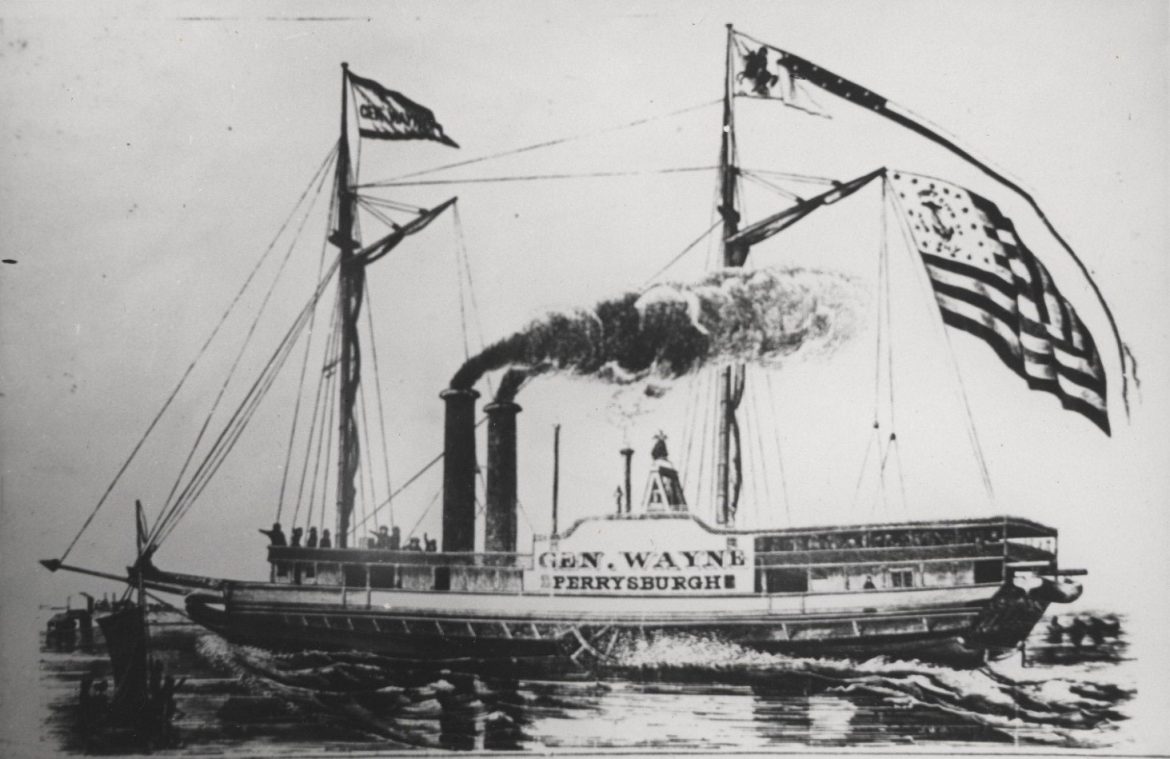

Clarence S. Metcalf Great Lakes Maritime Research Library of the National Museum of the Great Lakes

A woodcut of the Anthony Wayne from 1838. Image: Clarence S. Metcalf Great Lakes Maritime Research Library of the National Museum of the Great Lakes

One of the notable stories from the sinking was when Edward C. Gord, the ship’s captain, commandeered one of the two remaining lifeboats and with 10 other people left the wreck. Feeling there was nothing he could do to help the people still in the water, he sailed to the city of Vermilion, Ohio, to get help.

“Picture it’s pitch-black on a cold April night,”Kruger said. “People are frightened in the middle of the lake and the captain of the vessel leaves. He was exonerated but it was very controversial at the time.”

Another story describes a man bringing with him the remains of his wife and son aboard the ship. He used their coffin to keep himself, his daughter and another son afloat. Unfortunately his other son drowned.

“That brings to the life just the human story involved in these kinds of archaeological sites,” Kennedy said.

The Anthony Wayne went into service in 1837 and was used as a passenger ship. When there weren’t enough passengers, it also carried an array of cargo.

Hundreds of turkeys, pigs and horses were shipped next to barrels of seeds, flower, furniture, glue, trees, wine and books, Kruger said. “The ship had a long history as far as Great Lakes boats go. It primarily operated in Lake Erie, but also went to Chicago sometimes.”

While Kruger didn’t run into problems of algae or water pollution, one of the biggest obstacles is a problem Great Lakes residents know far too well.

“We came into contact with zebra and quagga mussels,” he said. “They just blanketed the entire wreck. It’s difficult to deal with these little monsters. They’re very sharp and on literally everything. When you try to remove them, they can actually sometimes pull off pieces of the wreck.”

Despite the obstacles, both Kruger and Kennedy were impressed by the level of detail intact on the ship. Coupled with the amount of historical data available, they were both confident about its potential nomination.

“We thought there was a very good likelihood,” Kennedy said. “That’s why we picked this wreck, the fascinating stories associated with it, how it exemplifies that pattern of history. The shipping, the freight on the lake is something we don’t think about as much today. So we knew it had this fascinating story.”