By Eric Freedman

Winter was the time of year when the North Woods rang with the sound of axes and saws felling giant white pines.

Winter was the time of year when the North Woods rang with the sound of axes and saws felling giant white pines.

It was the late 1800s, the Golden Age of American Lumbering, and the supply of trees was endless.

That last statement would prove untrue, of course.

In reality in northern Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota, the timber moguls, surveyors, speculators and lumberjacks were merely following the path of clear-cutting and exploitation that had already moved westward from Quebec and Ontario, from Maine and New Brunswick, from New England and New York.

Demand for timber seemed insatiable as Americans moved westward, building Midwestern cities like Chicago and settling the prairies of the Great Plains with farmhouses, barns and shops. Railroad routes stretched further and further, with their mega-appetite for wooden ties.

But what of the lumberjacks whose perilous labor built the fortunes of timber barons and who endured the hardships and hazards and isolation of those North Woods?

Life was in jeopardy. Death loomed as branches —widow-makers — fell, as logs jammed in rivers swollen with spring melt and as diseases ravaged lumber camps.

Franz Rickaby

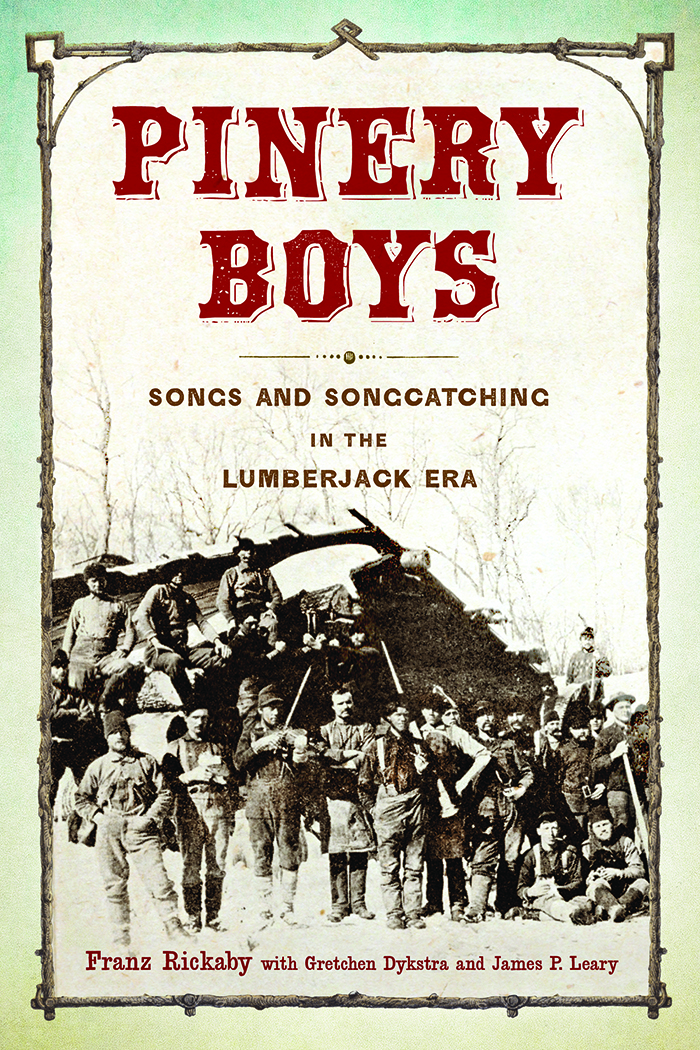

The “Pinery Boys: Songs and Songcatching in the Lumberjack Era” (University of Wisconsin Press) throws light on the lumberjack culture of the era. It’s a revised and retitled version of a 1926 book by Franz Rickaby, an English professor who traveled 917 miles, mostly by foot, from Charlevoix, Michigan, to North Dakota to collect songs of the “quickly disappearing” shanty boys, the lumberjacks.

Some songs describe them sitting around the lumber camps at night, smoking pipes, telling tall tales and playing music.

But others reflect harsher realities, such as this song about a tragedy in Minnesota “concerning a young shanty-boy so tall, genteel and brave. Twas on a jam on Gerry’s Rocks he met a wat’ry grave.”

And consider this one that contrasts recruitment promises with grim truth:

“It being on Sunday morning, as you shall plainly see

The preacher of the gospel at morning came to me.

He says, “My jolly good fellow, how would you like to go

And spend a winter pleasantly in Michigan-I-O?

The grub the dogs would laugh at. Our beds were on the snow.

God send there is no worse than hell or Michigan-I-O.

Along yon glissering river no more shall we be found.

We’ll see our wives and sweethearts, and tell them not to go

To that God-forsaken country called Michigan-I-O.”

Some lumberjacks left the Great Lakes region to fell virgin forests elsewhere. One such song tells of a “heart-broken raftsman from Greenville” who worked on the Flat River and whose name “is engraved on its rocks, sands and shoals.” Spurned by his sweetheart, he vows:

“I’ll leave Flat River, there I ne’er can find rest.

I’ll shoulder my peavey and start for the West.”

James Leary

The songcatcher, Rickaby, was “the source of deeply rooted insights into the gritty, almost forgotten reality” of the “singers and makers” of the songs of the North Woods, retired Professor James Leary of the University of Wisconsin, Madison writes in his introduction to the book.

Rickaby’s granddaughter, Gretchen Dykstra, writes in another chapter about his quest for songs.

“He slept in deserted camps on beds of cedar chips and in dark bunkhouses on grimy straw mattresses,” Dykstra wrote.

Gretchen Dykstra

Rickaby described finding two songs “from a toothless shanty boy in a small lumber camp” near Allenville, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula: Entering the lumber camp on an old logging road, “on all sides I saw the charred and fire-eaten stumps of what must have been magnificent trees, the hauling out of which this road was made.”

Coming out of the North Woods at the end of the season carried its own risks, many lumberjacks learned, especially the risk that their hard-earned wages could disappear quickly on liquor and women.

Here’s how one song put it:

“But here’s a proposition, boys; when next we meet in town,

We’ll form a combination and mow the forest down.

We then will cash our handsome checks, we’ll neither eat nor sleep,

Nor will we buy a stitch o’ clothes while whiskey is so cheap.”