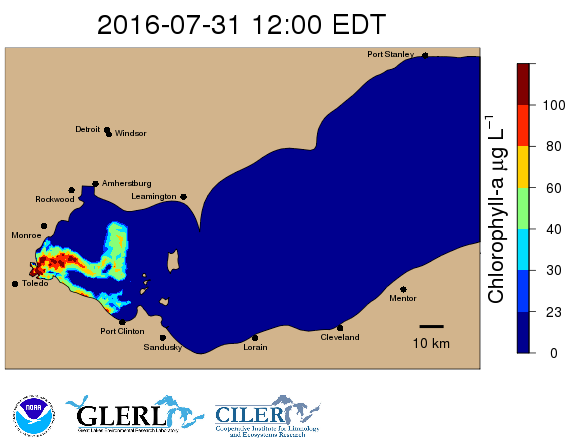

A still frame from July 2016’s tracked algal blooms. Image: GLERL/NOAA

By Kate Habrel

Planning a trip to Lake Erie? So is algae — the biggest blooms in the Great Lakes happen in its western basin.

The Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory’s Harmful Algal Bloom Tracker shows the location of harmful algal blooms — or HABs — and predicts where they will go.

It tracks the blooms using a combination of field sampling, satellite images and water current monitoring, like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s model of currents in the Straits of Mackinac. The blooms last from July to October every year, and the tracker gives daily forecasts during this period.

This could be especially important for treatment plants that get their water from Lake Erie.

Algae tinges Lake Erie green in an image taken by NASA’s Landsat 8 satellite. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

“A drinking water treatment plant operator from Cleveland looks at it every morning to see where our best guess is for where the HAB is located in Lake Erie,” said Eric Anderson, an oceanographer with NOAA.

The HAB tracker is still experimental, getting upgrades after feedback. But when it’s fully operational, it’ll run similarly to the weather forecasts on nightly TV.

A feature recently added to the Michigan tracker will show where harmful algae exists below the surface, Anderson said. If the algae gets close to intake pipes a few feet above the bottom of the lake, operators will be able to take precautions.

The model also works hand in hand with the Lake Erie HAB bulletin, which comes out twice weekly during bloom season. While the bulletin provides static images, the tracker is interactive and updated daily.

Blooms have been a topic of interest since the Toledo water crisis of August 2014 when drinking water from the public systems was banned for nearly 72 hours when it was feared contaminated with microcystin, a toxin produced by algae and that attacks the liver.

Lake Erie algae. Image: Flickr, Ohio DNR

“We’ve been having algal blooms in Lake Erie for almost two decades, but it was really ‘out of sight, out of mind’ for a lot of people ” said Tim Davis, a researcher with the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. “Then you have Toledo, where it’s not on the lake, yet there’s a half million people who may never go to Lake Erie all of a sudden have their drinking water turned off.”

Davis said algal blooms are a symptom of a larger problem in Lake Erie. High amounts of phosphorous and nitrogen were dumped in from mostly agriculture, causing algal blooms and hypoxia. Lake Erie was considered a dead lake in the 1960s and 70s.

Thanks to regulations, phosphorus is largely under control. But the problem of harmful algal blooms remains.

“Lake Erie is actually a perfect example of a lake that can be restored,” Davis said. “It’s going to cost a lot of money, and it’s going to take time, but if we reduce the amount of nutrients coming into Western Lake Erie, we’ll reduce the size and duration of the blooms.”

NOAA hopes to expand the HAB tracker to places like Saginaw Bay, Michigan, and Green Bay, Wisconsin. Both locations experience similar events to western Lake Erie. The group also hopes to be able to predict the toxicity of blooms, Davis said.