By Karen Hopper Usher

By Karen Hopper Usher

Kelly Wachter was supposed to promptly repay a $210,000 crop loan from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Service Agency. Instead, he paid off his wife’s student loans, bought a boat, a car and a truck and vacationed in Mexico.

Repayment wasn’t expected to be a burden at first, because the Wisconsin farmer had a big inheritance coming, Wachter’s lawyer said in a pre-sentencing letter to U.S. District Judge James Peterson in Madison

Now the 34-year-old is on three years’ probation and must repay $85,424.51.

“He was not a farmer who found himself in a tight circumstance,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert Anderson, who prosecuted the case.

Yet Wachter’s lawyer, Peter Moyers of Madison, described a perfect storm of bad luck and bad choices.

Wachter applied for a $210,000 loan in May 2014 to plant soybeans and corn on land he rented from his stepmother in Bloomington, Wisconsin. His father had recently died and he expected a sizable inheritance, according to a pre-sentencing letter.

When farmers take out crop loans, they list their intended buyers, Anderson said. The vendors are supposed to send payments directly to the department.

But that didn’t happen with Wachter’s crops.

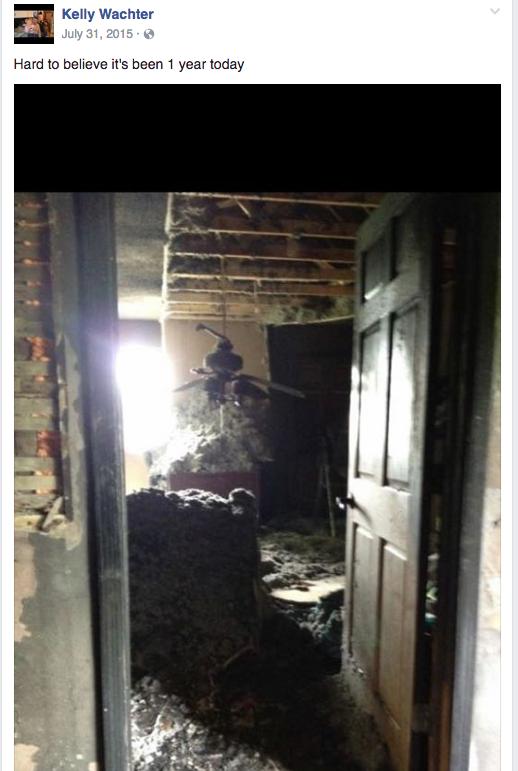

Kelly Wachter’s family home was destroyed in a fire. Image via a screenshot of Wachter’s Facebook page.

After the planting, Wachter’s home burned down and he moved with his family to Tennessee. Insurance didn’t cover all of his losses, according to Moyers’s letter to the judge.

Wachter hired a friend to take care of the crops, but cows damaged them anyway. Insurance didn’t cover that, either.

The crop sales brought in $108,000, just over half of what he’d borrowed, Moyers’s letter noted.

The crops were considered collateral for the loan, according to a press release from the U.S. Attorney’s office.

But the people who bought the crops weren’t the ones listed in the loan documents and they paid Wachter, not the department, prosecutor Anderson said.

After Wachter cashed the checks, he still didn’t pay back the department. Instead, he used the money on personal expenses, like vehicles and a vacation, Anderson said.

After the move to Tennessee, Wachter’s uncle died and he expected another sizable inheritance, according to his own letter to the judge. So he continued to spend.

“I spent an enormous amount of money in hopes of trying to save an irreconcilable marriage. But in the end it left me nothing short of broke, divorced and alone,” Wachter wrote.

Anderson said Wachter didn’t juggle funds to get by for the short time until the anticipated inheritance arrived.

“A $34,000 boat isn’t just a bag of ramen noodles,” Anderson said. In all, 40 percent of the loan paid for personal expenses.

The Farm Service Agency first approached Wachter in February 2015 about the missing funds and sent a demand letter in April. Wachter made a partial payment then and again in September.

Anderson said he suspects Wachter was simply trying to throw off investigators from the Agriculture Department.

“I did everything I could to undo the damage I caused in hopes of fixing the horrible decisions I made,” Wachter said in his letter to the judge.

But Anderson said, “I believe he knew what he was going to do when he took the loan out.”

Wachter pleaded guilty in October 2016. He faced 15-21 months in prison.

“I wouldn’t have been disappointed with 15,” Anderson said. But Wachter walked away from sentencing in early January with three months’ probation and an order to pay restitution.

His lawyer’s letter to the judge argued, “Wachter isn’t going to find himself in these circumstances again: a fire, an unraveling marriage, deaths in the family, and inheritances won’t combine again like this in his lifetime.”

Wachter owes $85,424.51. The federal government can take the money out of his tax returns until the debt is paid, Moyers said.

“It doesn’t go away. It just sits there until it’s paid off,” he said.

Moyers said he had no comment when asked if Wachter had any inheritance money left that could pay off the debt. Wachter didn’t return phone calls asking for comment.