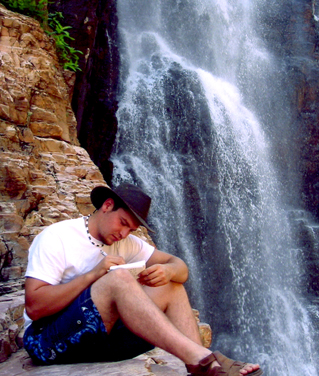

Scott Atkinson, Kakadu National Park, Australia, 2004. Image: David Poulson

Review

By David Poulson

I got to know Scott Atkinson in a Land Rover rattling through the Australian Outback.

That was in 2004 when he was a student in my study abroad class. I figured him for Hemingway-like aspirations. Within days of our arrival, he bought a kangaroo-hide hat that rocked an Indiana Jones vibe.

He wrote about our Aboriginal guide, a man who sought his ancient roots – connections that had been severed by a government policy that produced what is now called Australia’s Stolen Generation.

“He may not yet be Hemingway, but the kid knows a good story,” I thought.

Still does.

A dozen years later, Atkinson, a former Flint Journal reporter who now teaches

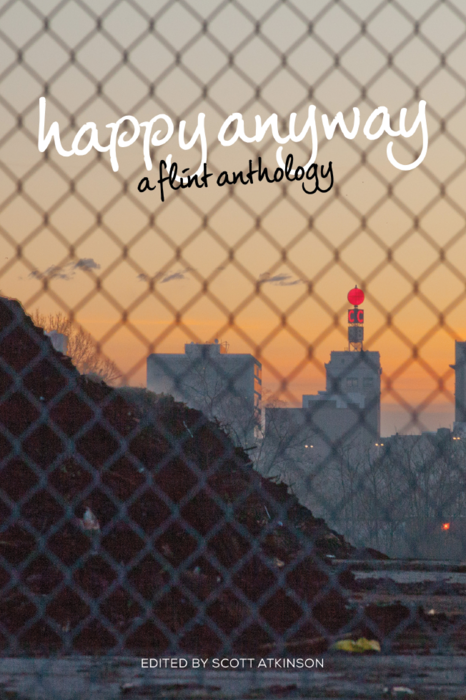

Happy Anyway is available for purchase via Belt Publishing and Amazon.

writing at the University of Michigan-Flint, has compiled an anthology of stories about America’s industrial Outback.

“Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology” (Belt Publishing, 2016) contains some of the first non-news stories published about Flint since that city gained international attention for the lead in its water. But these are stories that refuse to treat that crisis as the city’s defining moment. They barely mention it.

Like the story of most places, the story of Flint is deeply nuanced. The water disaster is just another challenge to overcome for people who remain defiantly happy.

Anyway.

That said, this is a book tinged with a deep poignancy. In “2302 Welch,” Will Cronin describes how shortly after he was born his father was said to have given him a tour of their house, inside and out.

“This is where you live,” the man whispered to his infant son. “This is your house.”

The anecdote launches a powerful narrative that would resonate in the neighborhoods of any industrial city in America, the kind with homes once built to “house the floodtide of the postwar American middle class” but now decaying with crime, poverty, ignorance.

“I have not seen our house since the day I drove the U-Haul away, but I’ve heard through the grapevine that its siding was stripped almost on the day we left,” Cronin writes. “Given the various rounds of demolitions the city has had in the intervening years, it may not even be there today. I expect I’ll learn of its fate one day, but I’m in no hurry.”

It’s a deep yearning for home, roots, connection – not unlike that expressed by that Aboriginal guide who had interpreted for us the petroglyphs of his ancestors.

And that’s why these stories are larger than Flint.

In “The Spirit of Sam Jones,” Bob Campbell tells of an uncle who turned a racial slur into a ticket to the middle class and became the kind of worker with as much of an impact on America as the Flint auto barons lionized with statues.

“For me, the usable past contains far more than those individuals immortalized downtown,” Campbell writes. “It also embraces Uncle Melton, whose fighting and enduring spirit helped build the city and drives it still.”

It is impossible to write about Flint without describing the passion of a community nicknamed Basketball City U.S.A. Patrick Hayes gives us several tales from Flint’s hardcourts, and not just of the fabled Flintstones who before the turn of the century laid the foundation for Michigan State University’s rise to national sports prominence.

There is the story of a high school and lower level college player from Flint, a solid player whose ball-handling skills were exceeded by his talent at self-promotion. He maintained an impressive social media presence and pestered sportswriters for coverage with fake emails signed by non-existent fans, Hayes tells us. He filled out paperwork for the NBA draft when he hadn’t played a college game in two years.

This isn’t a yarn about the limited opportunities for the immensely talented few. Hayes refuses to fault the self-generated hype but instead draws lessons from it: “But rather than get upset about it, it produced in me an eye-opening epiphany about the symbiotically exploitative relationship between athletes and the media.”

And yes, you also can’t write honestly about Flint without writing about crime.

“Flint’s death toll was actually its lowest total since 2009, but all it takes is to lose one person and the statistics go out of the window,” Eric Woodyard writes in “Fresh to Death,” a story about the shooting death of his good friend.

It was a death that produced deep conflict: “It’s a weird line that I have to walk — between downtown corporate Flint and where I was raised, between night and day, between the two different identities I’ve formed.”

Some of this is grim stuff. And you have to wonder about the title of this anthology. Atkinson in his forward says that “Happy Anyway: A Flint Anthology” reflects that these “are stories of triumph not because anything has been won, but because they are stories of Flint’s continued fight.”

So look hard. You’ll find Nic Custer’s story of a farming project that failed and yet pioneered the urban frontier. You’ll find Stacie Scherman’s portrait of her father – a man tough enough to run down and capture youthful vandals breaking the windows of his warehouse and sensitive enough to know that demanding restitution would just strain their already difficult home life.

You’ll find locked doors and open hearts: “For as many locks as there are in that town, and for as much as we all relied on them, people in Flint can be incredibly unguarded,” Stephanie Carpenter writes in “Flintlock.”

And Melissa Richardson will introduce you to the recreational pleasures of two city blocks of fresh-laid asphalt and of a muddy football game so epic that players later washed earthworms from their hair.

There is much more – stories to be savored and reread. It is some of the best place-based writing and reporting you’ll find anywhere. And you needn’t be from Flint to appreciate that.

Audio interview with Scott Atkinson here.

David Poulson is the editor of Great Lakes Echo and the senior associate director of Michigan State University’s Knight Center for Environmental Journalism.