Image: Connect Michigan

By Amelia Havanec

A vast majority of Michigan residents have access to high-speed Internet, a tool which the global marketplace increasingly relies on, according to the Telecommunication Association of Michigan.

Even so, pockets of the state still struggle with slow broadband speeds.

“The broadband industry is based on household density,” said Eric Frederick, executive director of Connect Michigan and Connected Nation’s vice president of community affairs. “Broadband providers need a certain number of customers in an area in order to make their build-out of infrastructure profitable.”

Connect Michigan is a nonprofit tech organization that works to expand broadband. At its annual conference this month, speakers pushed for innovative ways to raise the supply and demand for broadband infrastructure in rural areas.

he Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines broadband as high-speed Internet measured in megabits per second (Mbps). Advanced broadband, according to the FCC, measures out to 25 Mbps in downloading speeds, and a building with 10 to 25 Mbps is connected to decent home service. But the federal government sees as inadequate a region that can tap into only 9 Mbps or less.

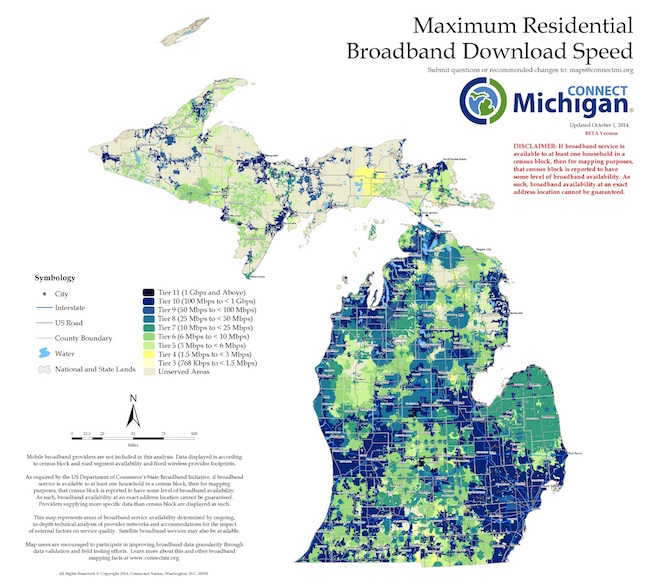

On Connect Michigan’s 2014 map of broadband speeds, “there’s a kind of ‘trouble band’ that starts diagonally from Oceana County up to Alpena County where broadband speed is really murky,” Frederick said.

The map also shows a great deal of the Upper Peninsula without adequate broadband technology — “because speed follows density,” he added.

Jaime Clover Adams, director of the state Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, says broadband connectivity is a top priority.

“We’re seeing a shift. We’re seeing more young people come back to the farm,” said Adams. “Michigan has such a diverse economy that people can continue to live in rural areas but they might work in town and have other sources of income.

“If we can get this broadband thing figured out, then people can live out in the rural areas and still participate in commerce,” she added.

Even in a state so agriculture-intense, there are food-processing companies that lack affordable and accessible high-speed Internet. Because of those constraints, some food processors struggle to break into markets across state borders, let alone world markets, said Adams.

Some big Internet service providers offer discounted subscription packages to low-income households, according to Frederick. Comcast, for instance, offers its services to qualified households for only $10 a month. CenturyLink and Charter Communications have similar programs.

“Affordability is so tricky,” Frederick stressed. “But if you don’t have access to any of those three providers, there is no rate regulation for broadband. The pricing is all over the board and you’re kind of at the mercy of the providers.”

A broadband connection can be defined as myriad Internet speeds– as more content moves online, a faster connection to the Web becomes increasingly important.

But Michigan residents, for the most part, have no problem accessing the Internet.

“When we look at availability and percent of households served in the south” of Michigan, “I think we’re probably around the middle of the pack” nationwide, Frederick said. “But when you look at broadband adoption —the percent of households that have service and actually subscribe to it — Michigan’s adoption of broadband is actually higher than the national average.”

According to data released in September by the U.S. Census Bureau, 72.9 percent of Michigan households subscribe to a home broadband service.

Scott Stevenson, president of the Telecommunication Association of Michigan, said, “There is a misunderstanding about how much broadband there already is in the state. Every one of the 36 rural broadband providers that our association represents has had broadband Internet in their networks for 15 years.

“So while there are pockets in rural Michigan without broadband, much of the state is covered.”

In August, AT&T, Frontier and CenturyLink, three of the state’s biggest providers, announced that they would expand broadband service, to 10 Mbps speeds, to an additional 180,000 households over the next six years.

“Some of our rural broadband providers are building underground fiber networks as we speak,” said Stevenson.

Fiber Internet provides the fastest speeds available and is more reliable than wireless networks, according to Stevenson, but it’s expensive to implement.

Asked about the feasibility of making broadband a municipally owned utility, like electricity and water in some communities, Frederick said Michigan is one of more than a dozen states where laws impede the creation of such municipal networks.

“But we have some communities that are successful in doing that in a shorter, more roundabout way,” Frederick added. “There are some communities that had broadband networks before that legislation went through,” calling Coldwater in Branch County “probably the best example.”

A Connect Michigan program helps local communities develop technology action plans, Frederick said. ”When we first looked at communities to do that, we were surprised. We heard things like, ‘We don’t want that filthy Internet here’ or ‘I moved to the country to get away from all that.’

“So we had to do a lot of education, which we don’t do so much of anymore,” he said. “People realize the importance now.”