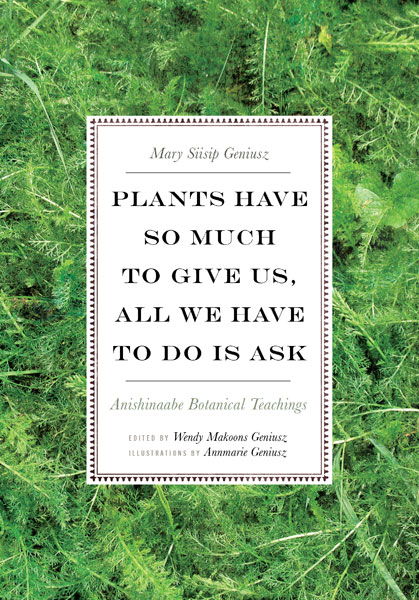

Mary Siisip Geniusz revives native Anishinaabe-Ojibwe plant knowledge with cultural and culinary anecdotes in her new book: Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask.

Mary Siisip Geniusz revives native Anishinaabe-Ojibwe plant knowledge with cultural and culinary anecdotes in her new book: Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask.

Three decades of archival research and on-the-ground practice rests on her belief that plants too are self-aware.

“As a traditionally trained apprentice or teacher, it’s important to talk to a plant as if it’s another human. You address the plant by name,” said Wendy Makoons Geniusz, the author’s daughter and editor.

The mother-daughter book project started when Siisip Geniusz rewrote years of notes from her time as an oshkaabewis, a traditional apprentice trained in ethnobotany — the study of relationships between people and plants.

Her notes, though originally meant for family, were edited by her daughter until they were published in June by the University of Minnesota Press ($22.95).

Much of the book hinges on the belief of an active and reciprocal relationship between plants and people. The Anishinaabe, a group and language indigenous to the Great Lakes, consider both plants and people cognizant.

By asking a plant’s permission to use it, a person acknowledges both what it provides and who it’s used for, Makoons Geniusz said. It also tacks on a spiritual component of health.

“While some Anishinaabe communities actively use plants, most do not,” she said.

Using plants means knowing them personally — using their names. And that’s a challenge.

Nokomis Giizhik or “my grandmother cedar” to the Anishinaabe. Image: Annmarie Geniusz

Many Anishinaabe plant names are lost in their communities. The book was in large part a search for these names.

“We started a hunt for the names with the help of Ojibwe speakers, but most were not properly recorded,” said Makoons Geniusz, who is an Ojibwe language instructor.

Notes of the late Keewaydinoquay, an Anishinaabe medicine woman from Michigan’s Leelanau Peninsula who taught Siisip Geniusz, provided the most help.

They helped produce a detailed glossary that lists Ojibwe words by origin and meaning.

This traditional language guides the manuscript, which Siisip Geniusz began writing in 2004.

Her daughter curated her notes, which stretch across two decades of Keewaydinoquay’s teachings beginning in the 1980s.

They separated chapters by plant type and cultural teachings.

The first chapter explains that the contents are neither “sacred” nor “secret.” They’re also not a substitute for modern medicine.

Instead, this collection of cultural annotations, stories and recipes preserves the knowledge cultivated by early 20th century Ojibwe grandmothers.

It gives insight into Anishinaabe cultural practices, critiques of land management including introduced species and the difficulty with translation.

Medicinal plants and recipes are cataloged from a number of native sources, offering over-the-counter remedies and healing stories from Keewaydinoquay and Siisip Geniusz.

The book includes botanist-approved illustrations of plants for identification.

Some remedies that require the experience of an oshkaabewis were left out because they contain “guarded knowledge.”

It’s an entry point to Anishinaabe philosophy and indigenous communities that have experienced cultural and spiritual loss.

“The stories connect people with the cognizant beings that are plants,” Makoons Geniusz said.

For instance, the second chapter reveals the vitalizing balance provided by cedar.

To the Anishinaabe, cedar is called “nookomis,” or grandmother. This familial name opens the line of spiritual communication and respects the plant’s cognizance, Makoons Geniusz said.

It recognizes the relationship between the Anishinaabe and the cedar, a plant that revealed all of creation — natural, spiritual and physical — to a lost people.

“The tree brought our ancestors to the present and can certainly bring us to the future,” she said.

Much like the story of the cedar, the book reveals that respect and permission precede harmony.