By Eric Freedman

Lynne Diebel’s canoe journey across the Driftless Area of Minnesota and Wisconsin took 359 river miles, 12 days and thousands of years.

Diebel’s journey started on the Cannon River, followed the Upper Mississippi and Lower Wisconsin rivers and crossed Pepin, Ohalaska and Monona lakes, with stops to camp on sandbars, trudge along portages and navigate locks more familiar with barge traffic than canoes.

Straddling Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa and Illinois, the Driftless Area avoided glaciation during the last Ice Age that ended roughly 11,000 years ago.

It’s a region that Diebel describes as “a rugged landscape of forested hills, deep coulees, bedrock outcrops and bluffs of caves, sinkholes, springs and disappearing streams of effigy mounds and geologic mounds of bottomland and blufftop farms.

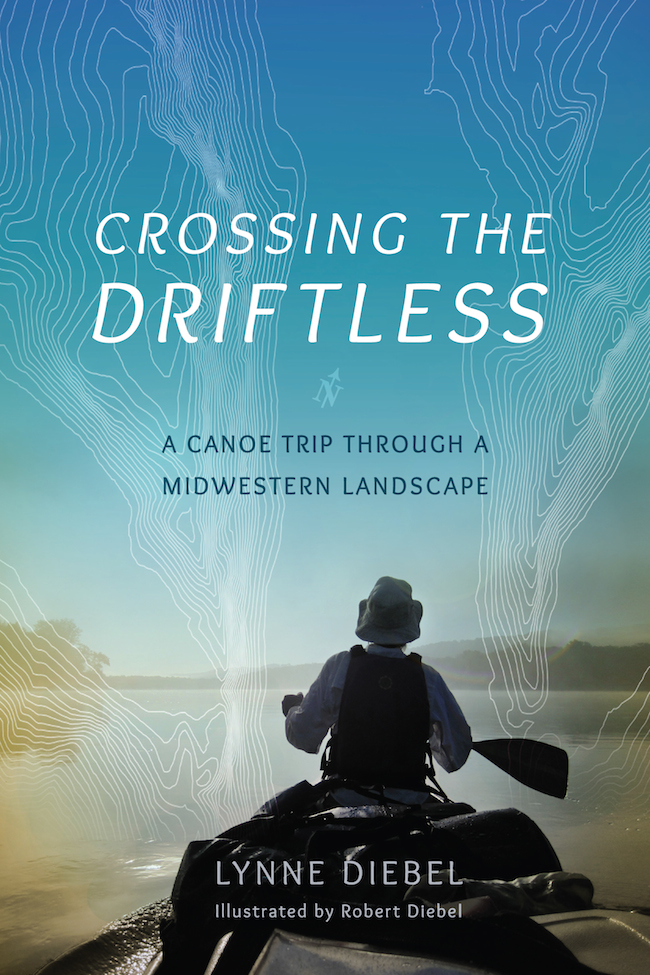

“And flowing down the many coulees and valleys is an intricate network of streams: countless narrow, fast-moving trout streams and quick-to-flood rivers,” she wrote in the newly published “Crossing the Driftless: A Canoe Trip through a Midwestern Landscape” (University of Wisconsin Press, $19.95).

Diebel’s canoe journey also traced a route of ecological damage from farm chemical runoff, dams and misguided construction and development projects. At the same time, it traced a route of remediation efforts by community activists and public agencies, as well as the route of nature’s inherent striving to heal itself.

“There’s a sense of connection you feel when you’re on a network of rivers. The relationship of tributaries and paddling a network rather than simply a river,” Diebel said in an interview.

“I wanted to tell people the way to love a river is to plan a very personalized trip,” she said. “That’s the way people get to connect to rivers. The more we care about a river, the more we’re going to do to protect it,” the travel guide writer and retired high school English teacher said.

Meanwhile, researchers have been searching for ways to encourage ecologically appropriate remediation in the Driftless Area. In one such endeavor, a recent study used 19th century U.S. Public Land Survey records to reconstruct the species of trees and vegetation that covered the region before Euro-American settlement.

Researchers from Iowa State University and the U.S. Forest Service said the study intended to assist “restoration practitioners” and land managers, as well as helping to set priorities for restoration that most effectively uses the limited funding that’s available.

“Ecological restoration efforts often seek to enhance the resilience and sustainability of ecosystems by directing them toward conditions that fall within their historical range of variability,” authors Monika Shea, Lisa Schulte and Brian Palik wrote in their article, “Reconstructing Vegetation Past: Pre-Euro-American Vegetation for the Midwest Driftless Area, USA.” It appeared in the December 2014 issue of the journal “Ecological Restoration.”

Their findings “depicts a landscape dominated by savanna and a variety of oak communities,” with a diversity of other species and a history of widespread, frequent and low-intensity wildfires, the study said.

“We consider restoring oak ecosystems an urgent restoration goal for the Driftless Area,” the study said. “Oaks are often foundational species where they occur, supporting a diverse array or plant and animal species. We expect declines in oak dominance and loss of oak communities to be indicative of substantial changes in ecosystem structure and function across the Driftless Area.”

As for the canoe journey across the Driftless, Diebel and her husband started in Faribault, Minnesota, near her family’s summer home, and ended in the Madison, Wisconsin, suburb where they live. She hadn’t planned to write a book when they set out in 2009 but kept a journal that provided the basis for “Crossing the Driftless” years later.

The book chronicles not only Diebel’s days of paddling, but also the natural history of the land alongside the rivers, the role of early explorers such as the 19th century French-American cartographer Joseph Nicollet, and the human and natural forces that have degraded the rivers and the land since then. It also chronicles activities by groups such as the Nature Conservancy, Ho-Chunk Nation, Kickapoo Valley Reserve Board and agencies such as the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and Wisconsin DNR to help nature right those ecological wrongs.

Diebel said she’s seen some gains in the six years since the canoe trip, such as improved populations of mussels on the Cannon and Upper Mississippi.

“That’s significant because of the role they play in being canaries in the coal mine for rivers. If they don’t thrive, if they don’t reproduce, that means the river is in trouble,” she said.

“They’re not thriving now but are increasing in their numbers very slowly,” she continued. “They’ve somewhat turned the corner.”

At the same time, however, Diebel expressed concern about mining sand for fracking in communities along the Lower Wisconsin.

“There are a lot of people who are passionate about the Lower Wisconsin,” she said.