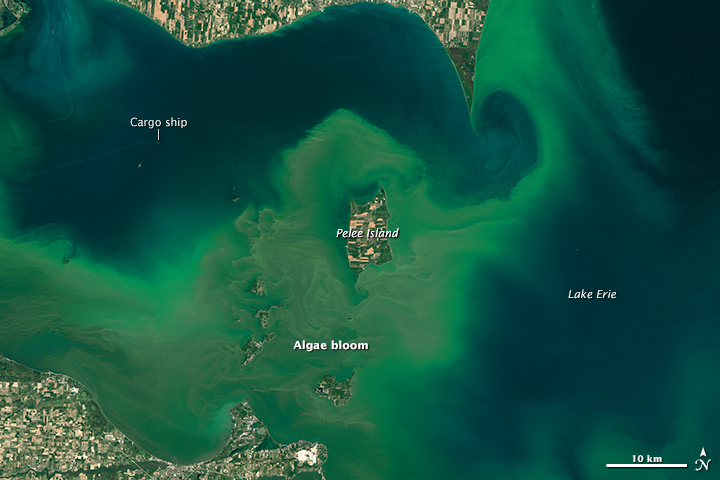

Satellite imagery captures recent algal bloom in Lake Erie. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

It might not be as addictive as Candy Crush, but a new EPA app could have big implications for water management and the people who drink, swim or fish within the Great Lakes.

The yet-unnamed app will detect blooms of cyanobacteria — a photosynthetic microbe often mistaken for algae and responsible for water quality headaches that particularly affect Lake Erie supplies.

It will use satellite data to give water managers a heads up of looming problems. Some day it may even allow you to check water conditions before you hit the beach — much like checking the weather forecast.

Cyanobacteria are found in both saltwater and freshwater. Under certain conditions they rapidly reproduce to generate large algal blooms. Cyanobacteria are bacteria, but they are often called blue-green algae because of their ability to produce their own food in the water.

Algal blooms disturb an ecosystem’s chemistry and may harm fish and wildlife. They’re also toxic and dangerous to humans, said EPA Research Ecologist Blake Schaeffer.

However harmful, the toxins generally cause minor rashes and irritations in humans, he said. They’ve rarely been linked to more severe complications like liver disease.

But large cyanobacteria blooms have shut down public beaches, polluting water and straining treatment facilities. Last year Toledo issued a two-day ban on drinking water for more than 400,000 residents because of the blooms.

Western Lake Erie is a focal point for large, difficult-to-manage blooms — something the app could help target.

The app maps the blooms and provides insight into what’s actually in the water, Schaeffer said. The idea is to assist states’ environmental management departments and educate the public.

“When people make decisions on whether they want to swim, fish or dive, they can use these maps to indicate [safe] areas they want to visit,” he said.

The EPA collaborated with algae-tracking experts at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NASA for the three-year project.

The app uses satellite data that tracks sediments, runoff, algae, bacteria and organisms like plankton that can change the water color.

“Very basically, these satellites function like your eyes do,” Schaeffer said.

Any body of water emits an array of hues caused by particles in the water, he said.

Suspended sediments — including small rocks, dirt and silt — makes water brown and cloudy. Clear water appears blue because it lacks these small materials.

In areas with large swaths of cyanobacteria, water becomes noticeably greener. The bacteria float on the water’s surface and limit light needed by many aquatic organisms.

“Your eye can differentiate all those colors, and the satellites can do the same thing,” Schaeffer said.

Satellites are a little more sophisticated though.

Algorithms and mathematical models help the EPA see how green, brown or blue the water actually appears, he said. It’s similar to the way weather apps acquire their data. And these experts hope it’s used the same way.

Blooms were recently observed off the East Coast near New York. They were likely the caused by nutrient-rich water from upwelling or treated sewage. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

Blooms occur across the country, including off the Pacific Coast of Oregon. Coastal blooms are thought to result from diatoms, which are phytoplankton like cyanobacteria that can be toxic. Image: NASA Earth Observatory

People dress for the weather — checking weather reports to avoid rain or snow, Schaeffer said.

“That’s kind of the long-term goal here, making these water quality maps very much like weather forecast maps,” he said.

The app will be released first to water quality departments and treatment facilities and later to the public.

The technology focuses on proactive responses to blooms, Schaeffer said. It will aid the effort to collect new samples, add filtration and monitor recreational areas for safety.

The EPA partnered with global business consultant Appirio, using its crowdsourcing platform Topcoder to develop the app through crowdsourcing, Schaeffer said. It involved many people and skills working inside the EPA and out. While functional, developers are working on a few remaining bugs. EPA hopes to distributed it to state water managers and health departments within six months. Their feedback will address any changes needed before the public release.

“I think that’s part of our role as scientists. We have to help communicate to people the work that we’re doing, and how it’s beneficial to them,” he said. And smartphones will help target this new capability to the everyday person.

Following its public release, the app will be available on the App Store and Google Play Store.

Of course preventing the blooms in the first place is better than detecting them after they begin to cause problems. Have an idea for that? You could win $10 million in a contest sponsored by the Everglades Foundation near Miami.

Great Lakes Echo reporter Kevin Duffy contributed to this report.