Hope isn’t a word most people associate with high-level radioactive nuclear waste.

But an upcoming documentary on its storage in Ontario takes an optimistic perspective on a depressing subject. It’s called Nuclear Hope.

“Hope can have a very positive meaning – we hope for a better future, we hope for a better life, all of those things,” said the independent film’s co-director, Colin Scheyen. “Hope can also be misguided. Without the right knowledge behind it, hope can be very shortsighted.

“Hope is a perfect word to use toward nuclear energy.”

Scheyen’s film explores the science and controversy surrounding the proposed deep underground storage of most of Canada’s high-level radioactive waste. That’s the extremely dangerous used fuel from a nuclear reactor – the most radioactive of nuclear waste.

The film hits select theaters and possibly a television network late fall, Scheyen said. It features interviews with nuclear experts, scientists, government officials and residents of nine areas that expressed interest in storing the waste.

The goal is to venture beyond the hot rhetoric to create real, informed discussion — which Scheyen said is nonexistent.

“No matter if you are pro-nuclear or if you are anti-nuclear, you at least have to come to grips with the fact that you have to do something about the waste,” Scheyen said.

“And maybe the best way to bridge this gap between people who are so vehemently against the nuclear industry and those so vehemently in favor of it is by coming to grips with how to deal with that waste.”

About 15 percent of Canada’s electricity is produced by nuclear plants. At 15,000 kWh each, Canadians annually use more electricity per person than almost any other country, according to the World Nuclear Association. Image: Nuclear Hope

A nuclear controversy

Canadian nuclear waste has been much in the news. In May, a Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission panel approved storing low and intermediate level waste created by Ontario Power Generation, a utility that supplies more than half of the province’s electricity. That waste would be stored underground at the utility’s Bruce Nuclear Site near Kindcardine, Ontario. The choice is controversial because it is close to Lake Huron and in a basin that provides drinking water for millions of people. The plan is open for public comment until September.

Low and intermediate-level radioactive waste includes gloves, protective clothing, machine parts and laboratory equipment — anything disposable that comes into contact with radioactive materials. It accounts for 97 percent of the world’s nuclear waste, but only about 5 percent of total radioactivity.

But Nuclear Hope is about the high-level waste managed by the Nuclear Waste Management Organization, a federal agency created in 2002. It is much more dangerous and takes significantly longer to decay.

What does Canada do with extremely radioactive high-level waste for hundreds of thousands of years? The question has implications for international relations and the future of the Great Lakes.

If you’re expecting Nuclear Hope to have an answer, you will be disappointed.

“I think that answer is much bigger than any one person or any one film,” Scheyen said. “It would be really arrogant for me to say I have the answer to the problem.”

Unlike other documentaries on the same subject, Nuclear Hope doesn’t choose sides. Scheyen and his co-director, Alberta filmmaker Shane Smith, didn’t look to argue a point — they just want you to.

The nuclear debate is clouded by misinformation, said Scheyen, also a writer and an educator.

“I think the anti-nuclear movement has been very good at using a lot of fear,” he said. “And, I will say, some of it is totally for the right reasons, and some of it for, I think, counter-effective reasons.

“And in the same way, the (nuclear) industry itself has told a lot of half truths, things that don’t necessarily give the full picture, but paint the industry in a positive way.”

A search for volunteers

Construction of the repository is more than a decade away. The federal agency is just beginning to choose a location. Nine areas are under consideration — all in Ontario, the home of most of Canada’s nuclear production. That’s down from an initial 22.

Nine areas in Ontario have expressed interest in learning what it means to host a nuclear storage site. Image: Nuclear Waste Management Organization

The candidate communities were not picked by the agency but volunteered to learn more about housing the waste, said Michael Krizanc, the Nuclear Waste Management Organizations communications manager.

“This community has to determine what it wants for its future, and whether this is the vision it has for itself,” Krizanc said.

But who would welcome a future with nuclear waste beneath their feet?

Housing the waste has its perks like more jobs, better jobs and near-guaranteed economic security and growth, Krizanc said.

“Some communities believe they are uniquely-positioned because they have a history of mining,” he said. “Other communities see this as something they can do on behalf of Canada.”

If all goes well, a site will be chosen within seven to 10 years.

Along with community approval, the proximity to aquifers and to mineral deposits that could encourage mining that threaten the facility’s structure are weighed. Rock stability for storage some 1,640 feet underground is considered.

This diagram gives an idea of what the proposed deep geological repository could look like, and how waste would be stored within it. Image: Nuclear Waste Management Organization

Construction would follow several years of testing.

The agency has to demonstrate the project’s safety to regulatory authorities, the host community and to all Canadians, Krizanc said. Communities are allowed to withdraw at any time.

Film trilogy planned

Nuclear Hope is to be the first of three films about the project. The second will cover the repository community and its residents when it is chosen. The third will be created many years after the repository is built. It will document how the waste site changes the community.

In the three years it took to produce Nuclear Hope, staff on the independent project that he and Smith funded never included more than six or seven people at a time, Scheyen said.

It takes a staggering amount of time before the radioactivity in nuclear waste falls to safe levels. Plutonium takes about a quarter of a million years to fully decay — about 12,000 human generations, according to the Nuclear Information and Resources Service. The repositories to house these materials have to be built to last just as long.

“It poses the question, how do you communicate with people who do not yet exist?” Scheyen said.

“It’s like as one gets older and has children, one begins to realize, it’s not just about me anymore, it’s about this child. I think that nuclear waste is like that in a lot of ways, because it forces us to not think about what is the best solution for us, but really, what is the best solution for people 1,000, 100,000 years from now.”

Can today’s solution become tomorrow’s problem?

Groups like Stop the Great Lakes Nuclear Dump worry that nuclear storage has serious environmental ramifications, especially so close to the Great Lakes. Beverly Fernandez, spokesperson for the activist group, said the risk of contamination is too big to take.

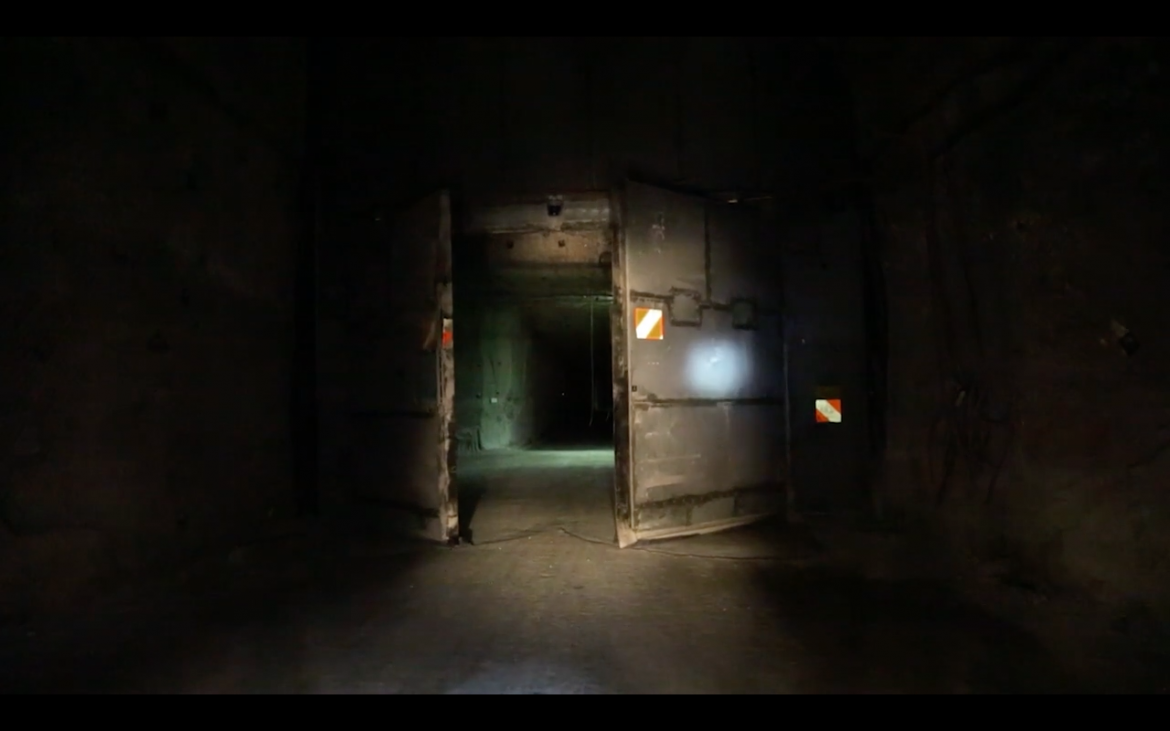

Scheyen filmed many scenes, including this one, in a decommissioned U.S. repository in New Mexico. Image: Nuclear Hope

Activist groups are circulating petitions and proposals that would ban the underground waste sites in the Great Lakes basin.

Even very short exposure to high-level nuclear waste is fatal to people. Indirect exposure is known to cause cancer and genetic mutations.

Today, the waste is stored within large, water-filled concrete pods reinforced with steel lining and standing on the surface of nuclear power sites. The water within the pods cools the waste and shields its radiation. The used fuel must be stored this way for at least 40 years before it is cool enough to move to permanent storage, according to the World Nuclear Association, an international organization that promotes peaceful nuclear energy.

“The material has been stored safely above ground for 40 years,” Fernandez said. “They can re-encase it in hardened concrete flasks that are bomb-proof, and that way they can be monitored for leaks.”

But the deep repositories are generally agreed to be the best storage for high-level waste, according to the World Nuclear Association. The storage pools at nuclear plants are not an appropriate long-term option, said Wolfgang Bauer, a theoretical physicist and university-distinguished professor in Michigan State University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

“You have to get rid of that waste,” Bauer said. “You cannot simply store it in the pods at the power plants. Eventually there accumulates too much of it. So, you have to have a long term solution.”

Most developed countries harness nuclear energy, but few have a permanent storage solution for its waste. Many countries have just begun discussing it. Others, like Finland and Germany, are building storage sites.

“The debate itself is, do we put radioactive material underground? Is that the best decision we can make?” Scheyen said. “Even the best geologist will say, you can never 100 percent guarantee that it’s going to work.”

As an Ontario-native, Scheyen said he feels responsible for the problem and its

Ontario’s wilderness is a contrast to the waste that could eventually lie beneath it. Image: Nuclear Hope

solution.

“I think this is an issue that really challenges our capacity to be responsible for what we’ve created,” he said. If we’re going to do this, we better make sure that everyone’s involved, and we’d better make sure that we’re doing it for the absolute right reasons.”

Nuclear Hope is being shown around the world this summer in places such as Montreal, Pakistan and Rio de Janeiro. Before the commercial debut, Scheyen hopes to screen it in the nine communities interested in hosting the site.

“That, to me, is a great opportunity to get the people in these communities talking, to actually create a room, an open space, where people can come together and have open and frank discussions about this,” he said.

As for the repository itself?

“All of this comes down to hope,” Scheyen said. “Hope for the best, hope that this is really the best solution. Because, when we’re dealing with something (for) hundreds of thousands of years, that’s all we’re really left with.

“We are only at the very beginning of this story.”