Federal, state officials are making progress cleaning up harmful chemicals in St. Louis, Michigan, but more work remains and there is still no comprehensive health study. Image: Brian Bienkowski

Editor’s note: This piece first appeared on Environmental Health News and is reprinted with permission.

ST. LOUIS, Mich. – During recent summers birds were found littered around the town, poisoned with a long-banned pesticide.

This summer? The school athletic grounds, where kids practice football and softball, are being dug up after it was discovered they too are contaminated with DDT.

It is the latest chapter in a seemingly endless effort to rid this small, rural mid-Michigan town of toxic chemicals that have plagued it since the 1960s. And, despite wildlife deaths and some lawns contaminated to levels deemed harmful to humans, no one is conducting health testing on DDT exposure in the community.

Schoolyard contamination

St. Louis, an hour drive north of state capital Lansing, has long dealt with contamination left behind by the Velsicol Chemical Corp., formerly Michigan Chemical, which manufactured pesticides until 1963 and abandoned loads of DDT, which was banned 40 years ago.

The pesticide was made famous by Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, which exposed the hazards of DDT, especially for birds, in 1962. Populations of bald eagles and other birds crashed when DDT thinned their eggs, killing their embryos. Exposure also has been linked to multiple health problems in humans, especially developing babies.

The pesticide, known for accumulating in food webs and persisting for decades in soil and river sediment, was banned in the United States in 1972. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency took control of the Velsicol site in 1982.

Last summer, after reports that robins and other birds were dying from DDT poisoning, state and federal officials started tearing up residents’ yards, removing contaminated dirt.

And this summer the toxic trail continues to wind through town.

This summer’s agenda includes tearing up 47 more yards, 10 city-owned properties, athletic fields at the local high school, and replacing St. Louis’ entire water system by tapping into a nearby community’s pipes.

The athletic fields–located at TS Nurnberger Middle School, which shares the fields with nearby St. Louis High School–contain levels of DDT harmful to wildlife, but not people, according to the EPA. In all, 6,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil will be removed by the end of July.

“We’re concerned about wildlife, like robins, there,” said Dan Rockafellow, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality’s project manager for the site. “It’s a short grass area, mowed, and anyone who mows grass knows it’s a preferred feeding area for robins.”

Officials found that robins in previous years died from eating contaminated worms.

Thomas Alcamo, the EPA’s remedial project manager for the site, said the EPA has been in contact with the school and that the levels are “not anywhere near” those that could hurt children playing in the area.

He said there have been other federal projects that have removed dirt for such low levels of contaminants, but it is unusual. “But it’s also unusual to have dead birds,” he said.

Jane Keon, secretary of the Pine River Superfund Citizen Task Force representing the community, said there was major flooding about 20 years ago, which left the school athletic fields under seven feet of water, depositing contaminated sediment from the nearby Pine River.

“We all assumed there was DDT on that field,” Keon said. “We kept telling the EPA that they should test there.”

The EPA sampled the fields last fall and sampled some more this spring. They are currently digging up the fields and estimate the work will be complete by the fall before the kids come back.

Yard cleanups continue; no health study for community

This year another 47 residential yards contaminated with DDT will be dug up and replaced with clean dirt and sod. In addition, 10 city-owned spots, mostly alleys, will be cleaned up, said EPA spokesman Francisco Arcaute in an email.

Contractors replacing the DDT-contaminated dirt in a resident’s yard last summer. This year another 47 yards will be torn up. Image: US EPA

The EPA has removed an estimated 25,000 tons of contaminated soil from residential areas so far, and plans on removing an additional 18,000 tons this year.

Rockafellow said they’re “looking to wrap up neighborhood stuff by this fall,” but that nine more homes’ yards will be sampled.

Like the athletic fields, most yards are being cleaned because the levels of DDT are a threat to wildlife. However, “five [of the 47 yards] have levels of chemicals of concern that exceed human health criteria,” Rockafellow said.

“We don’t know names,” said Gary Smith, a lifelong St. Louis resident and treasurer of the community task force. “They told us at one time 16 percent of 137 properties [prior to last summer’s cleanup] had elevated levels that were human health hazards levels, but there is no way to identify where that is.”

Alcamo said they’ve notified people whose homes have excessive levels of PBB or DDT and told them whether it’s higher than human health limits but haven’t placed any restrictions on access to the homes. “Considering the levels no additional measures need to be in place,” he said.

DDT is not just toxic to wildlife but humans too. Researchers have linked DDT exposure to effects on fertility, immunity, hormones and brain development.

Children and fetuses are at higher risk.

While four of those yards have DDT in excess of human health limits, one has excess polybrominated biphenyls, or PBBs, a flame retardant chemical Velisocol also manufactured and, in 1973, infamously mixed up with a cattle feed supplement, which led to widespread contamination in Michigan.

Thousands of cattle and other livestock were poisoned, about 500 farms were quarantined and people across Michigan were exposed to the chemical linked to cancer, reproduction problems and endocrine disruption.

Emory University is studying the people exposed during that mix-up and testing some blood samples for DDT.

Alcamo said a comprehensive health study of the community would be the responsibility of the state’s health department or the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, neither of which is studying the community.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services “is neither planning or currently conducting a human health study or an exposure investigation in that community,” said spokesperson Jennifer Smith.

Bird deaths drop

Matt Zwiernik, Michigan State University

For years St. Louis residents complained of dead birds. Last year they received confirmation that it was from toxic levels of DDT.

For years St. Louis residents complained of dead birds. Last year they received confirmation that it was from toxic levels of DDT. Image: Matt Zwiernik, MSU

A year ago Environmental Health News reported that birds were dropping dead in St. Louis, dying from DDT poisoning.

After years of complaints from residents, Michigan State University researchers tested 29 dead birds – 22 American robins, six European starlings and one bluebird – and confirmed the bird brains contained lethal concentrations of DDE, a toxic compound formed when DDT breaks down.

The bird findings last year prompted the first round of yards cleanups in a heavily contaminated nine-block area.

Smith, of the community task force, said there have been nine dead birds found and reported by residents so far this year, a much smaller number than in past years at this time. He estimated that two years ago, when researchers were combing the area for birds, they found roughly 60.

“This year we’ve got robins, finches, sparrows and some that you can’t tell what they are,” Smith said.

It is unclear if any the birds collected so far died from DDT poisoning, but they will be sent to the same Michigan State University researcher who tested past birds to determine their contamination levels.

New water system; plant site plans unknown

As part of the cleanup, St. Louis will piggyback onto the nearby town of Alma’s drinking water system.

The EPA bored down into the soil near the former plant site to identify areas that were most contaminated. Image: US EPA

The EPA and Michigan DEQ are paying $33 million of an estimated $45 million bill for new wells, pipes and pump stations. The EPA estimates the drinking water replacement should be complete by 2016.

There’s a chemical in the town’s drinking water called para-Chlorobenzenesulfonic acid (p-CBSA), a byproduct of DDT manufacturing with similar health impacts with long-term exposure. But it’s at levels that render the water still safe, Alacamo said.

The main reason for the new water system is cost to the EPA, he said. The agency has to pump and treat a lot of water at the former Veliscol plant site and it’s cheaper to give the city money to tap into Alma’s system than it is keep it in place, which would lead to more treating with expensive treatment costs.

What remains unknown is what will become of the actual site of the former plant. Every week, crews are trucking about 20,000 gallons of contaminated groundwater offsite. Rockafellow said the agencies have been boring down around the plant to test and see how deep and how wide the contamination is around the plant.

The EPA estimates that, after more testing, they will start cleanup at the former chemical plant site next year. Arcaute said the “site will be capped and we are hopeful redevelopment can take place.”

Alcamo said they plan on using many different technologies to remedy the site–including an innovative method using metal rods that heat up soil and capture vapors, destroying hazardous waste onsite.

“We still have to take that to headquarters and get funding though,” he said.

Not all bad news

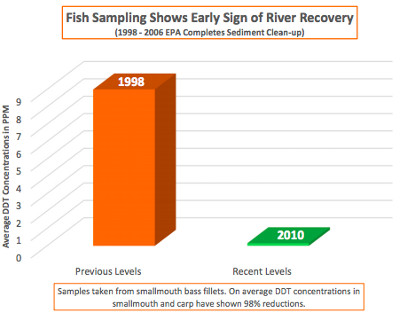

In addition to fewer bird deaths, there has been other progress. Arcaute said DDT levels in tested fish from the Pine River that runs through town have dropped roughly 98 percent since cleanup started.

Image: US EPA

Rockafellow said, however, there is contamination in the river and fish beyond that from Velsicol, meaning fish consumption advisories will probably stay for a while.

Keon also applauded the cleanup extending to areas such as the athletic field since it’s unusual to do so when there aren’t threats to people. “Finding birds that died from DDT poisoning helped the community have this kind of cleanup,” Keon said.

Both Keon and Smith said, for the most part, people who had their yards torn up last year were happy with the EPA contractors and their new, DDT-free yards.

But even though things seem to be moving in the right direction, residents remain skeptical current cleanup efforts will be enough to allow St. Louis to turn the page on this toxic chapter any time soon, Smith said.

“The community learned when this happened a long time ago, when the EPA says things like, ‘trust us we have our experts, and this is what’s going on, and this will work’, we have no choice but to be skeptical,” Smith said.

“We’ve heard all that before, and 30 some years later, we still have all of these problems.”

Brian Bienkowski is a former reporter for Great Lakes Echo who now writes for Environmental Health News.