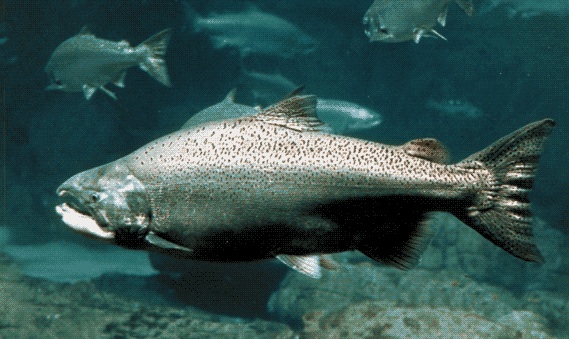

Chinook salmon with its preferred food, an alewife. The fate of both of these invasive species is linked. Image: Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory.

By Ian K. Kullgren

Natural resources officials are reporting record-low numbers of salmon eggs gathered at state collection sites in Michigan this year, evidence that could have implications for future fishing seasons.

In Manistee County, just 2,700 chinook salmon returned to the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) collection site on the Little Manistee River, down from a previous low of about 5,800 in 2010.

The same is true in Traverse City, where 1,300 fish returned, a notable drop from the 1993 low of 2,300. DNR workers trap the salmon in weirs throughout the summer season, and then harvest their eggs in the fall to be raised at hatcheries across the state

The cause, wildlife officials say, stems from the perennial competition for food with invasive species in Lake Michigan.

“It shines a light on how variable things are in the system,” said Edward Eisch, the DNR’s acting fish production manager. “The prey numbers are down, and they continue to be down year after year.”

In the mid-1980s, the Little Manistee weir harvested between 20,000 and 40,000 chinook salmon, according to DNR data. Last year, there were fewer than 6,500.

“That’s definitely alarming, and it’s a warning sign,” said Mark Tonello, a DNR fisheries biologist who monitors the Little Manistee River watershed. “We have very little control out there, and the only tool we have in the toolbox is stocking numbers.”

Collections for this year finished in mid-October, and the eggs have been transferred to one of three hatcheries located in Schoolcraft, Van Buren and Benzie counties, where they are being raised for release in May.

The hatcheries also raise coho salmon, steelhead and brown trout.

The fact that fewer fish will be raised and released in the spring doesn’t mean the 2015 fishing season will be worse than this year’s, said Tonello, who is based in Cadillac. Salmon spawns tend to run in three-year cycles and largely depend on how healthy the population of alewives – small fish that salmon rely on for food – was when the salmon were born.

He said 2012 was a good year for alewives, meaning anglers could actually have a better year in 2015 despite lower stocks this year.

Much of it depends on the winter and spring weather. Alewives are sensitive to cold weather and abrupt temperature change, so a spring like the past one could have a rippling effect on anglers’ success in futures seasons, said Heather Hettinger, a fisheries management biologist in the DNR’s Traverse City field office.

“It’s more indicative of the ecosystem challenges we have going on in Lake Michigan than anything else right now,” Hettinger said. “It’s going to be kind of hard to predict.”