Deep below the chill waters of northwestern Lake Huron, four doomed ships have been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Deep below the chill waters of northwestern Lake Huron, four doomed ships have been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

While nobody other than SCUBA divers are likely to see them up-close, their history and their tragedy are now increasingly accessible to the public.

The new official recognition of their importance is expected to spur efforts to list more of the Great Lakes’ hundreds of shipwrecks on the National Register, which the National Park Service describes as “the official list of the nation’s historic places worthy of preservation,” whether publicly or privately owned.

“There are so many shipwrecks in Michigan waters that this is a long-term project. We’re focusing on ones that are more complete and hold more of the history,” said Sandra Clark, director of the Michigan Historical Center.

“We’re always conscious of the conservation ethic. It’s better to leave things on the bottom of the preserve,” Clark said, adding that National Register status “reinforces the value of the shipwrecks and the idea these are historic treasures that should be preserved for future generations.”

There’s plenty of work ahead if government agencies, local groups or individuals want to get more wrecks placed on the National Register.

Lake Huron alone has 33 percent of the known wrecks in the Great Lakes, according to the Michigan Maritime Museum in South Haven.

Lake Michigan (21 percent) is second, with at least 1,000 ships lost, including more than 200 that grounded along the Michigan side of the lake, “most the victims of storms, some poor seamanship and others ever-changing sandbars,” a museum exhibit explains. Lake Erie followed with 19 percent, Lake Superior with 14 percent, Lake Ontario with 9 percent and Lake Clair with 3 percent.

Wisconsin and Minnesota have a variety of wrecks on the National Register.

Among those in Wisconsin are the schooners Gallinipper, lost in a squall in 851 near Sheboygan; the Hetty Taylor, sunk in another squall near Sheboygan in 1880; and the Fleetwing, lost in an 1888 gale at Garrett Bay.

Those in Minnesota include the steam naval sloop U.S.S. Essex that was burned in 1931 after the state Naval Reserve scrapped it in Duluth; the Samuel P. Ely, which sank at Two Harbors in a storm in 1896; and the canaller Benjamin Noble, lost at Two Harbors in a 1914 storm.

Indiana has only one, the Muskegon, built in 1872 and scuttled in 1911 off Michigan City after being severely damaged by fire.

Michigan had only a few listed before the four Thunder Bay wrecks were added. Among them:

- J. Hackett, a steamer that sank in Lake Michigan in the Upper Peninsula’s Menominee County in 1905.

- Hennepin, A steamship that sank in Lake Michigan in Allegan County in 1927.

- Byron, a schooner that sank in 1868 in Lake Huron in Presque Isle County.

Russ Green, the deputy superintendent of Thunder Bay Marine Sanctuary based in Alpena, Mich., said there are 92 known sites within the sanctuary’s borders and another 100 “yet to be discovered just in our neck of the woods because Lake Huron is the crossroads of the Lakes.”

The papers nominating the vessels as national historic sites said, “These submerged archaeological sites form nearly a complete collection of Great Lakes vessel types from small schooners and pioneer steamboats of the 1830s, to enormous industrial bulk carriers that supported the Midwest’s heavy industries during the twentieth century.”

In early September, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which runs the sanctuary, expanded its boundaries from 448 square miles to 4,300 square miles adjacent to Alpena, Alcona and Presque Isle counties stretching to the Canadian border.

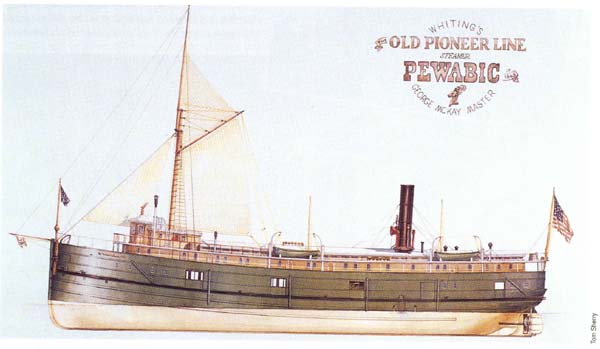

The four newly listed wrecks — the schooner M.F. Merrick, the bulk freighter Etruria, the passenger/package freighter Pewabic and the schooner Kyle Spangler — sank between 1860 and 1905. Two of them were discovered by researchers working with students from Arthur Hill High School in Saginaw.

The best known of them, the Pewabic, went down near Alpena in Lake Huron’s worst maritime disaster. A few months after the Civil War ended it collided with another ship and sank, dragging “250 tons of native copper” from Keweenaw Peninsula mines in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and “many of its 125 passengers” to the bottom in only four minutes, the National Register nomination said.

Green said the sanctuary’s Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center in Alpena will interpret the four wrecks through exhibits and artifacts.

“The maritime landscape is the story,” he said. “If you look at Lake Huron, it’s flat. We’re telling you that under it is history. It’s literally locked in time with ice-cold waters.”

The Michigan Historical Center’s Clark cited several major reasons to seek federal designation for shipwrecks.

“In reality, not that many people can see a shipwreck, but when you get something on the National Register, you have the information in a place where a lot more people can read about it and benefit from the work done,” she said.

In addition, listing may reinforce the state’s legal ownership of all wrecks on Michigan’s bottomlands.

“Occasionally people challenge that ownership. One way you solidly protect that ownership is to go through the process of getting them listed on the National Register. It provides one more step in legal protection.”