Grain yields under three alternative farming systems from 1989 to 2012. The dotted horizontal line represents yields under conventional management. Source: Farming for Ecosystem Services: An Ecological Approach to Production Agriculture

Rotating corn, soybeans, winter wheat and cover crops could cut nitrogen and herbicides use by two-thirds and produce similar or slightly higher yields.

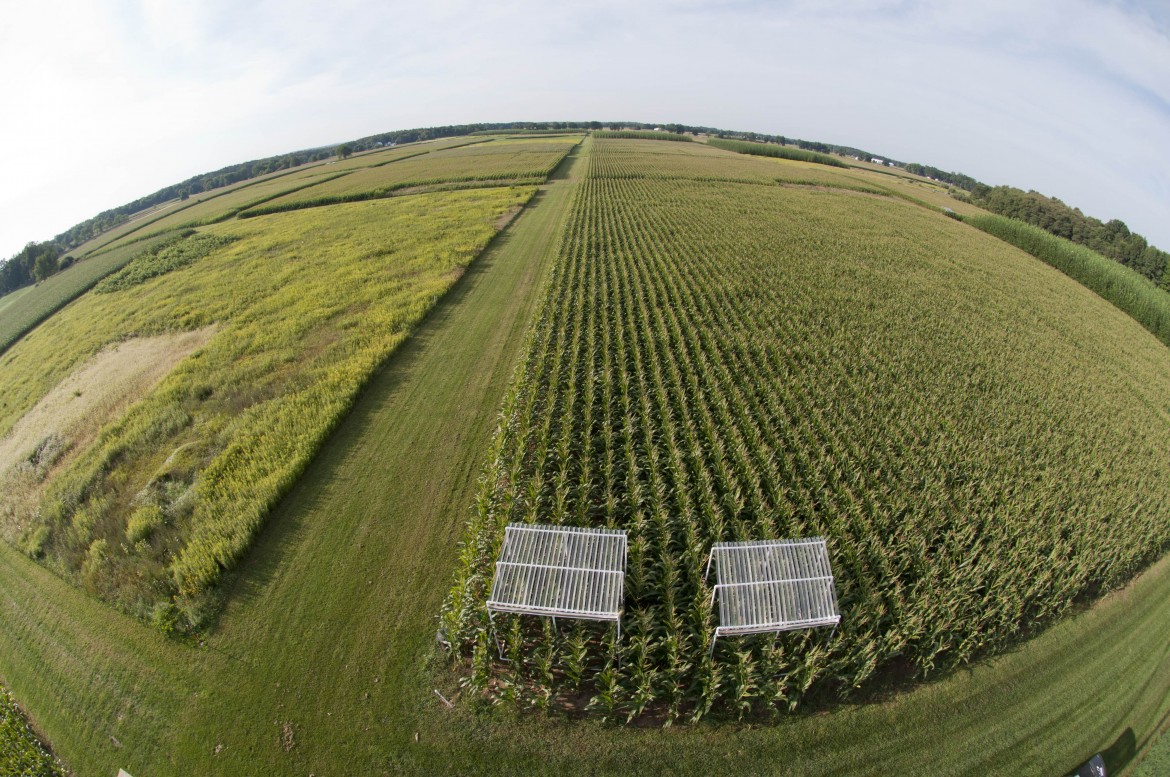

That ecological farming formula is developed by experts at Michigan State University’s Kellogg Biological Station, a National Science Foundation Long Term Ecological Research site about 16 miles northeast of Kalamazoo, Mich. It’s a formula that could preserve soil fertility and be easier on the environment.

The research, based on 25 years of experiments, appears in the May issue of the journal BioScience.

The researchers also studied farmers’ willingness to adopt the environmentally friendly practices and conducted a statewide survey of whether people are willing to pay for those practices.

Nowadays many farmers grow only one or two crops on a plot of land. They produce more food on less land with the help of fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides. However, such modern farming can harm the environment, according to the research report titled Farming for Ecosystem Services: An Ecological Approach to Production Agriculture.

A Kellogg Biological Station test plot for testing how crops respond to reduced precipitation. Image: K.Stepnitz, Michigan State University

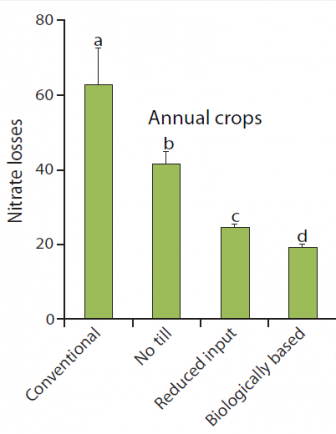

Nitrogen and phosphorus can pollute groundwater. Pesticides can kill helpful and other non-targeted organisms. And some farming methods can produce greenhouse gases, such as carbon and nitrogen dioxide, that contribute to an unsteady climate, the study said.

The study emphasizes that agriculture not only provides food and fuel, it also provides clean water, biodiversity and climate stabilization. These benefits are called ecosystem services.

The researchers evaluated the yields and environmental benefits of three alternative farming practices.

No-till cuts costs, greenhouse gases

One is no-till farming, which avoids the cost, labor and negative impacts of plowing.

Phillip Robertson, an MSU AgBioResearch scientist and lead investigator of the research, said plowing breaks up soil which helps microbes decompose stored organic matter faster. That process emits more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Annual nitrate leaching losses from several farming alternatives between 1995 and 2006 at Michigan State University’s Kellogg Biological Station. Source: Adapted from Syswerda and colleagues (2012).

Without plowing, however, carbon accumulates as organic matter in the soil instead of getting released in the air as carbon dioxide. That reduces greenhouse gas emissions and makes soil more fertile, he said.

Many farmers will use no-till for only one or two crops in the whole rotation, said Marilyn Thelen, an MSU extension agent.

“Permanent no-till is probably not accepted as widely as having no-till as part of their system,” she said. “Part of the problems the farmers have had is that oftentimes no-till is difficult to get good seed-soil contact.”

When the soil is cold and wet, if farmers “work it a little bit,” the plowing will make the soil dryer and provide better soil conditions for the seed to grow.

But Thelen said in the past 30 years farmers have been minimizing the impact of tillage by plowing very shallow, “like maybe three inches,” to maintain the residues in the soil.

Robertson said practicing no-till just for a short time doesn’t provide much greenhouse gas benefit. So providing some incentives for farmers to use no-till for longer periods could be a way that society could reduce pollution and stabilize climate, he said.

Without plowing to remove weeds, the no-till model needs more herbicides for weed control.

A second model, the reduced-input system, could reduce by two-thirds the need for synthetic nitrogen and herbicide inputs, according to the research.

Cover crops to improve soil, reduce erosion

In this model, researchers use cover crops during cold conditions when many major crops don’t grow. The cover crops improve soil quality and reduce soil erosion. Cover crops are usually planted and left on the land. In the process they take nutrients like nitrogen and maintain it in the plants as biomass for the next crop to absorb as fertilizers. Meanwhile, they keep soil from getting washed away by rain. “Oats, oilseed, radishes and cereal rye are the most used types of cover crops that I see the producers using,” said Thelen.

Reducing nitrogen fertilizers benefits the environment, said Scott Swinton, an MSU agricultural economics professor and a co-author of the study.That’s because fertilizers generate nitrogen dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas.

Also, they cause more nitrates to leach into groundwater and send nitrate runoff into surface waters, Swinton said. These excess nutrients in rivers and lakes feed algae. When the algae decompose, they use up the oxygen for fish and other water organisms.

A willingness to pay for ecosystem services

Swinton works on understanding the economic factors that farmers consider when making production changes and the willingness of consumers to pay for them.

Profit is one important factor influencing farmers’ decisions, he said. Some practices that the researchers studied increase labor costs, like managing cover crops. Some may lower yields, like simply reducing fertilizer use.

But Swinton said that under certain circumstances it’s possible to reduce chemical fertilizers while maintaining yields by changing farm management like planting cover crops.

Robertson said the ecological impacts from those approaches “are very important to the environment and very beneficial for people. The market now does not value these services enough and doesn’t pay for them, so the farmers have no incentive to endure the extra cost to provide these services.

“A whole class of benefits that cropping systems can provide to people is likely unrecognized and uncompensated,” he said.

The researchers also looked at consumers’ willingness to compensate farmers for adopting ecologically beneficial approaches. A survey of 2,400 households showed that many are willing to pay higher taxes to help farmers adopt farming practices that lead to a better environment.

What makes this research most unique is its long-term nature, Robertson said. That allows researchers to explore questions that can only be answered by long-term observations and experiments.

Organic soybean field on MSU’s Kellogg Biological Station’s Long Term Ecological Research station near Kalamazoo, Mich. Image: J.E. Doll, Michigan State University