Native vegetation slows water runoff, prevents erosion, absorbs pollutants and provides wildlife habitat. Photo: Huron Pines

By Leslie Mertz

Property owners believe their waterfronts are more natural than they really are, according to a recent University of Wisconsin survey.

That’s why governmental and environmental agencies have a hard time convincing them to adopt native-plant shorelines that are critical to a healthy lake ecosystem.

Those are among the findings from a research project to identify why property owners prefer a manicured lawn and to learn how best to persuade them to go natural instead.

Now in its fifth year, the research centers on two small lakes — 519-acre Long Lake and 229-acre Des Moines Lake — in northwestern Wisconsin’s Burnett County.

“Years ago, these lakes used to be in larger parcels of course, but as people grew old and passed them on, the parcels got split,”

said John Haack, a research leader and regional natural resources educator for the University of Wisconsin Extension in Spooner, Wis.

The few larger parcels that remain have native plants that provide wildlife habitat, increase biodiversity, improve water quality and enhance the lakes’ scenic beauty. But very little, if any, native vegetation remains on the vast majority of smaller parcels, which make up most of the lakeshores.

Researchers found that lakefront property owners already thought their shorelines were plenty natural. After Haack and another biologist evaluated the shorelines lot-by-lot, the researchers asked the lot owners to rank their own waterfronts.

While the biologists described 82 of out of 163 lots as groomed (mowed lawn to a sandy beach), the residents listed only four of the 82 as groomed. They characterized the other lots as 58 mixed (part natural and part groomed) and 20 natural.

“People think they’re somehow better than others or above average — it’s just human nature,” said Bret Shaw, one of the research leaders and an associate professor in the Department of Life Sciences Communication at the University of Wisconsin — Madison. Those rose-colored glasses carry over to an individual’s property, and in this case, the lakeshore.

A survey of lake property owners revealed that they view their shorelines as considerably more natural than biologists do. (As-yet-unpublished data courtesy of John Haack and Bret Shaw.)

To persuade these property owners to adopt natural shorelines, environmental agencies must first get them to see that the waterfront needs improvement, Shaw said.

“One way is to distribute a checklist so people can objectively go through their shorelines and see how an ecologist or naturalist might view their lakeshore,” he said. “It’s difficult to fully sync up an ecologist’s perception with a property owner’s, but this is a way to hopefully get their perceptions closer.”

Based on surveys, focus groups and tests of educational materials and marketing efforts, the researchers found:

- “People like their beaches. They’re not going to get rid of them,” Shaw said. That means that environmental agencies need to tell residents how to carve a small beach out of a natural shoreline.

- Less is more. Rather than distributing to property owners a long list of native plants from which to choose, the researchers identified 10 native shrubs and 10 wildflowers for Burnett County and worked with a grower to stock them at local nurseries. Coupons encouraged residents to buy native vegetation for their waterfront.

- Property owners worry that taller vegetation blocks their view from the house to the lake, where children often play. For good sight lines to the shoreline, researchers included short-growing varieties on the shrub list.

- Birds are good motivators. People like wildlife and want more of it on their lots. Researchers targeted marketing materials to explain how natural shorelines increase the number and variety of songbirds.

- “One of the things we learned was we have to give people options,” Shaw said. Some residents might decide to simply quit mowing by the lakeside and let native plants come back naturally from seeds that are still remaining in the soil. Other property owners might prefer what they consider to be pretty native plants and install those instead for a more planned appearance.

- Properties are used by multiple generations. “They want to spend time with their children and grandchildren, and also in many cases to pass the house down and feel like this is going to be part of a family legacy,” Shaw said. “That led us to create educational materials that allowed grandparents or parents and kids to interact with each other and to understand lake ecology better.” The materials include a Wisconsin lakes trivia game and a youth field journal of activities children can do with adults.

Preliminary results from a follow-up survey over this past winter show that the promotional efforts, including three restoration projects designed to show residents how a natural shoreline can be added, worked.

Compared to 2008, more residents now prefer their shoreline to look “completely natural,” Haack said. “We’ve been successful in raising awareness about the benefits (of a natural shoreline) and increasing the desirability of a natural aesthetic, which is more important to me.

“Raising awareness doesn’t take us anyplace, but the shift in desirability suggests that in the future they are going to be more open to actually doing it.”

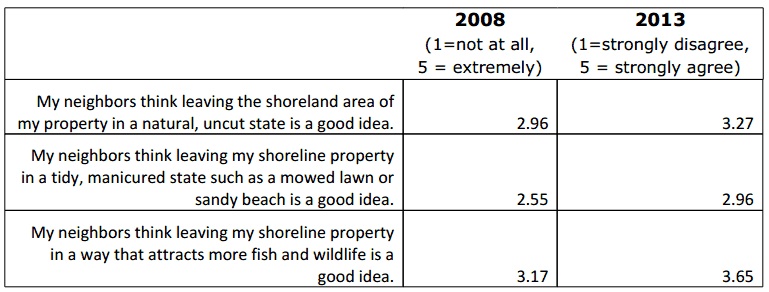

Haack was especially heartened by property owners’ views about how their neighbors would

More lake property owners believe their neighbors are supportive of natural shorelines now than five years ago. Data: John Haack and Bret Shaw

respond to a natural shoreline. The surveys asked them to rate from 1 to 5 statements such as “My neighbors think leaving the shoreline of my property in a natural, uncut state is a good idea” and “My neighbor thinks managing my shoreline in a way that attracts more fish and wildlife is a good idea.”

“We bumped those up,” said Haack, noting that increases were about a quarter to a half a point, which he described as a good improvement for a five-year program.

Haack and Shaw hope this research helps other Great Lakes environmental agencies encourage lakeshore owners to upgrade to a natural shoreline.

“I hope that we can at least share with agency folks at the county level and the state level that when we develop educational materials in regard to shoreline, we need to be really strategic about it and think about what the barriers of and benefits to those people are,” Haack said.

“I know it costs a little more money and it’s going to require more staff, but if we really want to be at least incrementally effective with some of this stuff, we’re doing to have to do that.”

Said Shaw, “Even though we were focusing on two lakes in (this work), the objective obviously is to find out what’s effective and what’s not, and then scale it up on a state-wide basis, or at least to areas in Minnesota, northern Wisconsin and other places with lots of smaller lakes.”

This research is important, said Patrick Goggin, lake specialist with University of Wisconsin Stevens Point.

“Understanding the barriers people have to conservation work and what we can do to lessen these obstacles is important to lake communities achieving success with restoring habitat,” he said. “It also helps us in building up the confidence and capacity of lake citizens and aids them in achieving these kinds of best management practices for lake protection.”